Of all the galleries in the Tate empire, the one that seems most comfortable in its own skin is Tate Liverpool. The rest are an increasingly dysfunctional bunch. Poor Tate Britain appears psychologically incapable of doing what it was set up to do — to celebrate British art — and yearns, desperately, to be Tate Modern. Tate Modern itself, meanwhile, has grown so unfeasibly huge, it is now a place you go for the foyers, not for the art. As for Tate St Ives, there has never been a pressing reason for it to exist, and its fate, alas, is to fiddle away at the margins of art, being ignored.

Tate Liverpool, however, goes from strength to strength. Everything works here. The Merseyside location is thrilling and fun. The agenda to serve the north is clear and tangible. The size of the building is perfect for looking at lots of art, but not too much. The locals are some of Britain’s most charming people. And — most important — the exhibition programme gets it right, time after time after time.

Life in Motion, an inventive pairing of the art of Egon Schiele and Francesca Woodman, is a striking example. On paper, it reads like the kind of show you would get if you blindfolded your granny and told her to throw darts at a list of 20th-century artists. Schiele was a scary genius of Austrian expressionist painting. Woodman was a little-known American photographer of the 1970s. What possible reason could there be to bring them together?

There turn out to be many, all pertinent, all adventurous, and all the result of the best kind of curation: the kind that makes you see things. Decades of history and thousands of miles of geography separate Schiele from Woodman, but they shared important hopes that are universal and crucial, and which the exhibition makes legible. The result is a Bonnie and Clyde of a show, packed with sex, glamour and law-breaking, but also with tragedy.

Schiele (1890-1918) is the marquee name here. Working in Austria in that brief cultural moment when Vienna became the centre of the universe — Freud, Mahler, Klimt — he exploded onto the art scene with some of the fastest hands ever to pick up a pencil, and a crazily precocious vision that saw the human body as a window onto the mind. In Schiele, the bodies writhe because the minds writhe. The fact that he died so young, just 28, from Spanish flu, gives his career the tragic arc of a rock star.

Much the same turns out to have been true of Francesca Woodman (1958-81). Born in Denver, Colorado, of parents who were both artists, her life was so brief, she barely had time to graduate from college before she was dead. Suicide. Throwing herself from a window in Manhattan. But in those few absurdly short years, she managed to develop and sustain a compelling and important career as a poetic and haunting photographer. As they say in football: if you’re good enough, you’re old enough.

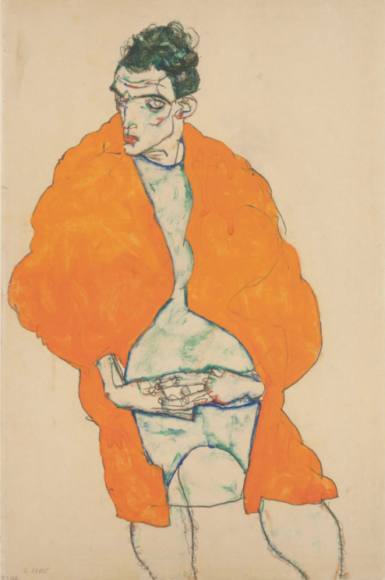

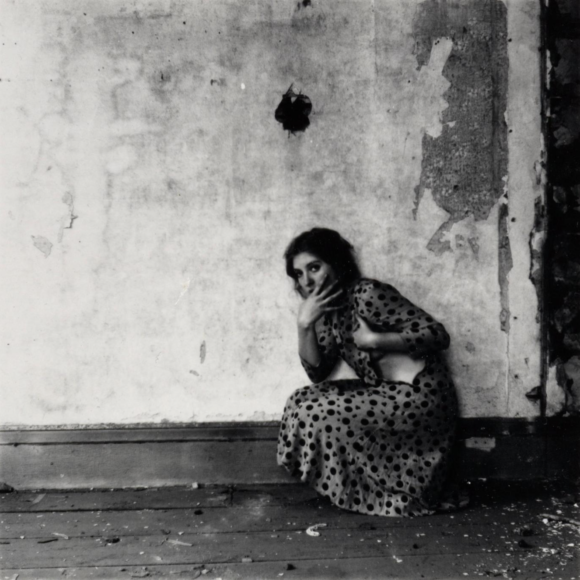

By calling itself Life in Motion, this clever Tate event wants us to focus on Schiele and Woodman’s shared interest in human movement. The way we stand. The way we contort. What we can do with our bodies. So the first things we see here are his drawing and her photograph of two uncomfortable figures.

The Woodman features Francesca herself crouching on the floor in a decrepit room, cowering against the wall as if frightened by an intruder. One hand clutches her breast. The other covers her mouth. The photo is black-and-white, and a tad shaky, so there’s an atmosphere of silent cinema about the scene: The Perils of Francesca.

The adjacent Schiele is a back view of a man pulling off his coat, struggling with it, as if someone has tied him up and he’s trying to escape. Under the coat, he’s naked, and Schiele’s furious mark-making makes something spiky and awkward of his movements. It’s just a coat, but it feels like a straitjacket.

It’s a brilliant opening. The impact of both artists is immediately fierce. And the sense is immediately created of a pictorial dual between parallel forces. A man and a woman. Both intense. Both narcissistic. Both obsessively aware of the emblematic power of nudity. Both fated to die grimly and prematurely.

Having allowed them to share a wall for its opening, the exhibition never does it again. Instead, it tracks their progress in alternate blocks of art. Schiele, with his extraordinary touch, is quickly impressive. His pencil was a wand. There’s a famous story of him using a stopwatch to see how fast he could draw, and the result of all the speed practice is one of the surest hands in art. His subject is always the human figure, but what crazy fun he had inventing short cuts to describe it.

Crouching figures. Figures seen from above. Figures hunched, huddled, cramped and twisted. It’s as if he’s made a bet with someone that he would never repeat a pose that has already been used in art. As for the sex scenes — warning: there are lots of them — they are spectacularly frank and appear determined to accuse the sex scenes that came before them of coyness and politeness.

Woodman, too, is immediately convincing. There’s no preamble. At 13, she was already producing precocious self-portraits in which she presents herself in a scruffy room, staring out through her hair, insisting you notice her from a distance. From the start of her bit of the show, to the end, the mood never wavers. It’s always a Sylvia Plath mood: risky, outrageous, self-harming and demanding attention.

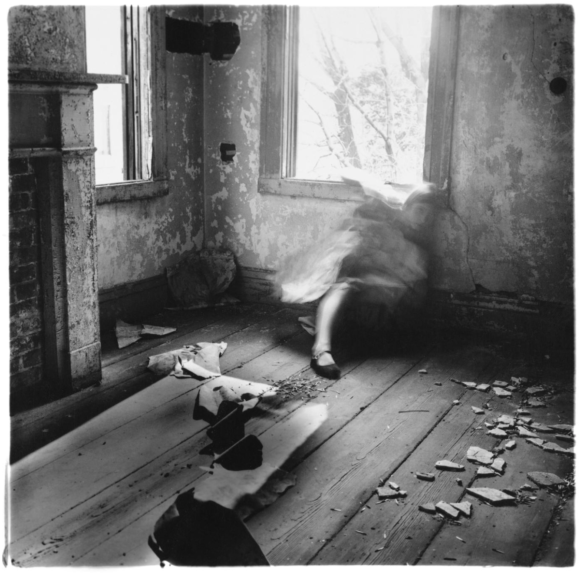

Most of the imagery features Woodman herself, often nude, always at the edge of focus, presenting herself to us in mysterious circumstances. She’s in a room. She holds a mirror. Presses herself against glass. Hurts herself with clothes pegs attached to her nipples. There’s a fetishistic air to this deliberate discomfort, as there is with Schiele, and a sense of Victorian terror. A beautiful girl in an empty room is forcing us to spy on her.

This edgy mood is what gives her art its consistency. But it’s not what gives it its beauty. The beauty comes from the poetic use she makes of her medium and, indeed, of herself. Every photograph is black-and-white. All are small and square. All are gelatin silver prints — the most atmospheric of printing methods. There’s a sense, therefore, of being taken back in time to a pioneering moment in photography’s history. It’s an illusion. But a gorgeous one.

In the end, what most firmly unites the quick-fingered Viennese expressionist and the dreamy Manhattan selfie pioneer isn’t the tragic brevity of their moment, but the psychological fierceness of their art. The way they yank you into their thought processes. The violence of their call.

As I said, this is a Bonnie and Clyde of a show, but with an undercurrent of something universal and eternally plangent. Something that goes back to Adam and Eve.

Life in Motion: Egon Schiele and Francesca Woodman, Tate Liverpool, until Sept 23