As the train puffed south towards the Mediterranean, Van Gogh, who was on his way from Paris to Arles in February 1888, kept looking out of the window to see “if it was like Japan yet”. Paris had grown harsh, damp, squalid. In Arles, on the edge of Provence, he hoped to find a life in the sun, full of nature, love, happiness. So he was escaping. But what is fascinating here is that the happy life he dreamt of escaping into was specifically Japanese in colour and tone.

Thus begin the events traced in detail by Van Gogh & Japan, a riveting show at the Van Gogh Museum, in Amsterdam, that looks back at Vincent’s obsession with Japanese art and the career-changing impact it had on him. Most Van Gogh shows that concern themselves with his time in Arles seek to deal with his notorious ear-cutting and the disastrous stay of Gauguin. But not this one. Gauguin gets barely a mention. The ear-cutting is avoided entirely. By approaching Van Gogh from a Japanese angle, his artistic story can be told freshly and buoyantly.

In truth, the display never concerns itself overmuch with reality. From start to finish, from his discovery of Japanese prints in Paris to his final Hokusai-style painting of rain lashing down on the cornfields at Auvers-sur-Oise, painted three days before he shot himself in 1890, Van Gogh’s Japan was an unlikely dream masquerading as a happy possibility: a desperate projection of hope. There are many reasons why this is such a compelling show, but the one that haunts me is that everything here — the colours, the interpretations, the imaginings — constitutes a misunderstanding.

Van Gogh never went to Japan. All he learnt was learnt from art. He began his mental voyaging in earnest in 1886, when he started to acquire Japanese woodcuts in bulk from Siegfried Bing, the most celebrated Parisian dealer in such things. Van Gogh, whose family included a powerful arm of art dealers, hoped to make money reselling them to pals and collectors. Paris — indeed, much of Europe — was in the clutches of a passion for all things Japanese, and this Japonisme, as the craze was called, had been proving lucrative. But he was as hopeless at being an art dealer as he was at most of the more mundane aspects of life, and ended up with a huge stock that he could not, or would not, part with. Instead, it began flooding his imagination: charging him and changing him.

An early and clumsy example on show here, a flower study from 1886 of chrysanthemums and delphiniums in a blue and white vase, sees him painting the flowers against a thick black background in an effort to mimic the appearance of Japanese lacquerwork. An adjacent example, a real Japanese panel inlaid with ivory, shows us the exquisite effect he was after. But in Vincent’s thumby hands, the thick splodges of black paint that mimic the lacquer succeed only in making the poor flowers look crude and funereal. It’s like watching someone trying to bang together a Buddhist temple out of two-by-fours.

But the most remarkable thing about Van Gogh — the miracle of Van Gogh — is the speed and totality of his transformation from effortful journeyman to painterly genius. Having started his love affair with Japanese effects so clumsily, he proceeds to gorge on them, intoxicate himself with them, absorb them, conquer them and soar with them. And it only takes him a couple of years: the couple of years he has left.

The show’s opening move is to spell out what it was that he took from the Japanese art he was collecting so busily. Above all, he took colour. In Japanese woodcuts, the unnatural colours — strong reds, vibrant blues, bright yellows — were laid down in flat patches, pure and glowing, with little ambition to appear realistic. The colours were there because they were beautiful and striking, not because they were trying to mimic the effects of the natural world. So, in Arles, in the sunshine that flooded the Provençal skies once spring had sprung, Van Gogh began to enjoy and employ colour with a new intensity.

Almost immediately, in a matter of weeks, his art became delirious with pleasure at the sight of all the yellows he discovered around him. Yellow lemons huddle together in a yellow basket on a yellow background in a yellow frame. Madame Ginoux, who owned the cafe next door to the famous Yellow House, in which he lived, is painted against a yellow brighter than the colours of the Brazilian football team. Not in the show, but a hop and skip away in the Van Gogh Museum’s permanent collection, are the glowing Sunflowers that make the point most famously. From Japanese art, Van Gogh learnt to worship colour for its own free reasons.

It’s the story of the show, and it is told to us with an exciting mix of Van Gogh paintings — some unfamiliar loans from private owners and some spectacular ones from American museums — and the Japanese prints relating to them, many of which come from his collection, preserved at the Van Gogh Museum. Indeed, there’s a section here in which his Japanese prints have been carefully reattached to the wall through the same pinholes he originally made and used! So it all feels extra-authentic and intimate.

And it isn’t only the Japanese adoration of colour that changes him. So, too, does Japanese perspective. A helpful computer graphic makes clear how he would tip up his perspectives to make the foregrounds bigger. A beautiful alcove, filled with rapid drawings made with a homemade pen cut from a passing reed, sees him looking dramatically down on the land from a Japanese height. By bravely cropping his foreground trees and rocks and branches, he pushes them dramatically to the front. These were tricks learnt from Japanese woodcuts. All of them come with the stage whisper that great art does not need to be realistic art.

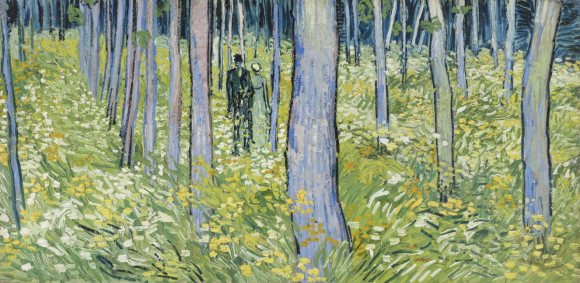

While this technical stuff is being made clear to us, something less explicable is also happening in the show. It’s just as important, but harder to track: a change in emotions, an inner journey. You see it most evidently in the unassuming natural subjects he begins to choose in Provence. Cabbage whites fluttering about a poppy. A peacock moth on a leaf. The base of a tree surrounded by a happy jumble of weeds. The famous depictions of peach and plum blossom, marking the end of the winter.

This is art with a devotional relationship to nature that is new in European painting. Nature isn’t merely being recorded here, it is actively being worshipped: held up as something enchanting and transformative. The nature studies that begin to crowd this journey are filled with an ecstatic animism gobbled up from the woodcuts on his walls. Hokusai, Hiroshige, Kunisada taught Van Gogh that you don’t need huge sunsets over the sea or gigantic cliff faces in the snow to describe the power of nature. It can be described, delicately and Buddhistically, in a twig of almond blossom or the merry flutterings of a cabbage white.

All this is made clear by an important show. Here and there, it’s a little too “coffee table” — big paper screens with vague Japanese quotations on them — but in the main, it stays on the right side of informative. By confronting so much evidential painting with so many evidential prints, the exhibition’s organisers make their conclusion inescapable: Japanese art turned Van Gogh into Van Gogh.

Dam it all: a dutch art trip

The Van Gogh Museum is at Museumplein 6, in the heart of Amsterdam. It’s open daily. The £16 entry fee covers both the Van Gogh & Japan show and the main collection, which has the world’s biggest holdings of the artist’s work. Tickets, which are timed, must be bought online at vangoghmuseum.com.

While in the area, visit the excellent Stedelijk next door — open 365 days a year, admission £15 — for art and design from 1880 onwards. The Stedelijk Base collection of 700 works offers all the big names in modern art, from Malevich and Mondrian to spot-lover Yayoi Kusama; stedelijk.nl.

Eurostar now goes direct to Amsterdam, taking 3 hours 41 minutes: singles start at £35. Note that you have to change trains in Brussels on the return trip.

Van Gogh & Japan, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, until June 24