Welcome back, the Hayward Gallery. We have certainly missed you. Your two-year closure for a big spruce-up has robbed us of inventive theme shows and witty retrospectives. The textures of the art world have felt flatter in your absence.

What the Hayward brings to the party is a genuine independence of vision: a sense that the crowd is being led, not followed. Hayward shows don’t preach, accuse or bang the drum. They dart about the perimeters of art, making clever connections and delightful observations. It’s all down to the impressively wacky vision of the gallery’s director, Ralph Rugoff, who, I am delighted to hear, will be the artistic director of the next Venice Biennale, in 2019. Bravo, Ralph Rugoff. Two fabulous new train sets to play with.

That’s the good news. The less good news — way short of bad, but problematic in places — is that the gallery has chosen to reopen with a vast retrospective devoted to the German “photographer” Andreas Gursky. I have put “photographer” in quotes because what Gursky is, what his work constitutes, is one of the issues with him. It is something we need to come to. But first we need to worry about his direction.

Gursky is a looker-down on things. Much of his work adopts a high vantage point, from which it gazes at the rest of us as we scuttle about our daily lives and produce our daily patterns. A typical Gursky will look down on a huge space in which people are at work — bankers, computer manufacturers, furniture makers — and note the crazy busy-ness of the human ants beavering away in Babylon. The world is being observed from a divine viewpoint. It’s a viewpoint that has occasionally made me bristle.

The spaces of the Hayward — open-plan, walkwayed — have always struck a mildly sci-fi note. And so, in this instance, does the art. It’s an impression heightened by the loftiness of the spruced-up galleries. The new ones upstairs are a revelation. Their scale is suddenly heroic, and it is pretty obvious, pretty quickly, why Rugoff may have chosen to open proceedings with a Gursky show. A huge, dystopian world-view, in huge, dystopian photographs, is a dramatic start to the gallery’s new chapter.

We begin with early work. In the 1980s, Gursky studied in Düsseldorf with the celebrated duo Bernd and Hilla Becher, whose classroom also produced Thomas Ruff, Thomas Struth, Candida Hofer: a museum-load of important German photographers. The chief lesson taught by the Bechers was that the ordinary world is fascinating, and that every centimetre of it is worthy of photographic attention.

It’s a lesson Gursky took quickly to heart, with a series of lookdowns at our everyday antics. A marvellous view of a swimming pool, from 1987, shows the people around the pool posing, stretching, flirting, squabbling, an animation sequence of human interaction made to feel more telling by the absence of shirts and tops. It’s as if we are looking down on the specimens in a behavioural experiment.

Another early photo shows a river flowing through a mountainous forest, dividing the land into dramatic slabs. It feels like an Ansel Adams photo, a pure celebration of nature’s wonder, until you notice the tiny fishermen huddled messily on the river bank, like unwanted bits of litter. It’s the show’s first confrontation between man and nature. Many more are to come.

The display ahead is loosely chronological — too loosely chronological. With leaps of decades being made in some of the spaces, it is difficult to gain a tangible sense of Gursky’s progress. There’s not much variation in mood, either. Just that insistent sense of separation.

So it is left to individual photographs to punch through the shiny film of photographic uniformity. The scientific revolution that enabled Gursky to create his giant images — the invention of supersized photographic paper in the 1980s — changed the impact of photography on a nuclear level. In previous eras, photographs needed to be peered into. In Gursky’s era, they needed to be stepped back from. The sense of overview you get from him, the God’s-eye vision, gives his art the import of a history painting.

Photographing the Chicago Board of Trade in 2009, he confronts us with a hellish scramble for money worthy of a circle in Dante’s Inferno. Screaming traders, flashing computer screens, demented numbers, a floor strewn with litter — it’s a vision of human greed that would make Hieronymus Bosch blanch.

Twenty years earlier, in 1990, in his first masterpiece in the accusatory whopper genre, Gursky had looked down on the docks in Salerno, Italy, and noticed how uniform everything had become. Rows of identical cars. Rows of identical containers. Rows of identical houses. That disquieting Pete Seeger song Little Boxes sprang immediately to mind: “Little boxes on the hillside/Little boxes made of ticky tacky/…Little boxes all the same.”

The grim uniformity of the human impact on nature in the Salerno whopper is emphasised by a beautiful ring of mountains encircling the despoiled bay. Gursky’s romantic appreciation of nature, his fondness for mountains, seas and lakes, has a Friedrich-like tang to it. He is far too measured and modish an artist to accuse us explicitly of desecrating the sanctity of God’s kingdom, but image after image seems to whisper: nature, good; man, bad.

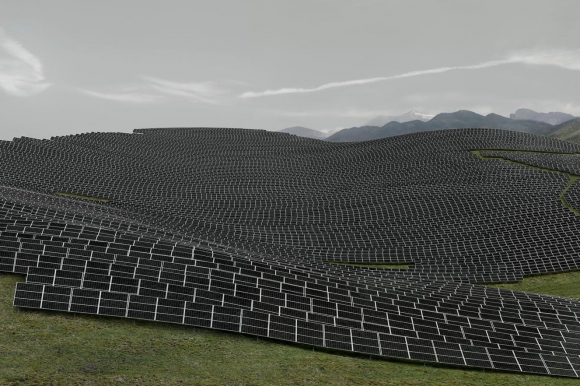

A view of El Ejido, in Andalusia, where the vegetables are grown under plastic sheets surrounded by a thick carpet of plastic litter, is the fiercest of the accusatory nature photos. Perversely, the plastic sheets form a pretty abstraction. So do the solar panels laid out in an extraordinary sea of smothering technology across the rolling hills of Les Mees, Provence. It’s a sinister sight.

Repetition is one of Gursky’s favourite strategies. He loves to observe the patterns created in nature by us specimens. But this appetite for repetition exaggerates the sense of repetition in the show itself. Yes, the photos get bigger and bigger, but in terms of artistic vision, the beginning does not feel massively different from the end. Except in one area — the increasingly artificial nature of the “photographs”.

I have unleashed the quotes again because the precise status of Gursky’s produce is eminently debatable. Most of his later views have been constructed from multiple close-ups, layered together and Photoshopped. They look like photos, but they are actually digital collages. Things are never quite as bad as he makes them out to be.

He is, of course, doing what artists have always done: confronting us with his viewpoint. But photography has a particular relationship to truth. Fiddling with it in this sneaky fashion adds layers of complexity to Gursky’s meanings, but it also violates a trust and makes me feel uneasy.

Andreas Gursky, Hayward Gallery, London SE1, until Apr 22