Citing national stereotypes is a perilous business in matters of art. No sooner have you pointed out that this or that nation has a tendency to do this or that, when along comes someone who does none of those things. Occasionally, however, it is useful to lump together national tendencies. It can clarify and resonate. And that is surely the case with the German photographers. They changed art. But what is really interesting about them is that they changed it along clear national lines.

The German photographers — Thomas Struth, Thomas Ruff, Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Thomas Demand — are pioneers who yanked photography out of its A4 era and turned it into something that could command a loft wall. But their work wasn’t only consistently huge. It was also consistently thoughtful, rigorous, precise and steely. So apologies to the entire German nation for the crass generalisation that follows, but German photographers brought Vorsprung durch Technik to their art.

Of course, an important reason for this consistent tone is that they all studied in Düsseldorf in the 1970s under the brilliant Bernd and Hilla Becher. The Bechers were proponents of a nerdish black-and-white photography, one that collected, sorted and archived: photography as science. And this taste for Linnaean clarity was something they passed on.

The fine Thomas Ruff retrospective at the Whitechapel Gallery, however, makes it pretty obvious there was more to it than that. Also tangible is a dour national mood that pulls Ruff in a dour national direction. The silences strike you as quintessentially German silences. The obsession with precise technology is something you simply do not find in, say, Italian art. Most telling of all, the gloomy sense of history that underpins Ruff’s images is huge, but under the surface. Sorry, but it prowls like a U-boat.

Ruff was born in the Black Forest in 1958. He got interested in photography as a teenager and fetched up in Düsseldorf, where the Bechers were photographing their famously faceless water towers. Until the Bechers, it was generally incumbent upon a photograph to be catchy and memorable. But the Bechers did away with catchiness. Instead, they kept photographing and rephotographing those water towers in a flat and joyless rhythm that seemed somehow to describe the rhythm of postwar Germany.

You feel it in Ruff as well. Here he shows us two big streetscapes set blankly in a blank German suburb. Puddles in the road. A sky so colourless and unmarked, it could have been made in a factory. Buildings fashioned from a mix of concrete and hopelessness. As imagery, it deflates the spirits like a dumbbell dropped on the chest. This — a prompter’s voice whispers from the wings — is what happened to the Bauhaus dreams.

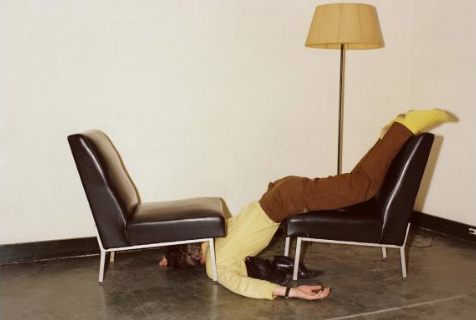

Surprisingly, the show starts with a moment of humour. Or rather with an attempted moment of humour that doesn’t work. Finding himself in Paris in the 1980s, Ruff discovered nothing among the city sights that floated his bateau, so he photographed himself instead, clambering across bits of furniture in the room in which he had been quartered. The poses he adopts — leg in the air, head under a chair — are supposed to be “absurdist”. But instead of achieving absurdity, they encourage you to notice how dull his room is and marvel at the organisational skill involved in taking these joyless pictures. Once he’d clicked the shutter, how did he succeed in getting over to the furniture, adopting the silly poses, and still manage to make the effort look so unhurried and dreary?

It turns out to be the only time that Ruff features himself in his photography. The pictures with which he first made his name were the huge, minutely detailed portraits of his friends and students produced between 1981 and 1991, and they remain his most haunting work. Their atmosphere is the atmosphere of the photo booth. The sitters are presented as a head and shoulders, unsmiling, staring straight ahead, against a white background. But where photo-booth portraits are tiny and vague, Ruff’s giant loomings give his ordinary German sitters the monumental presence of an Easter Island head. Looking at them becomes a process of getting lost in a stranger’s face.

The references to photo booths are typical. Most of the thematic clusters in the show are as concerned with how an image was achieved as with what it presents. Ruff roams from porn films to surveillance cameras, from the face-recognition machines used by the West German police to old industrial photography rescued from a deserted factory. So interested is he in photographic processes that he sometimes forgets the hardest and fastest of all photography’s rules: the image has to grab you.

His giant heads do it. The bleak streetscapes do it. The blurry porn pixellations do it. But I’m less convinced by the gaudy photographic approximations he produces from the colour schemes of manga comics. All manner of digital processes are involved in the making of these noisy psychedelic abstractions. But good abstraction depends on an instinctive grasp of shapes, thrusts and colours that Ruff does not have. Why should he? He’s a photographer.

That said, the show in general does not deserve my carping. Varied, atmospheric, enterprising, this is photography boldly going where no photography has gone before.

Thomas Ruff, Whitechapel Gallery, London E1, until Jan 21