Not for the first time in my life, as I left the new show at the National Portrait Gallery, I was moved to mutter: “Thank heavens for the Queen.” Once again, Her Majesty had saved the day. Were it not for her loan of a wall full of commanding Holbein drawings from the Royal Collection to the exhibition entitled The Encounter: Drawings from Leonardo to Rembrandt, that exhibition would be a poor event. Short on quality. Short on direction.

It is the fate of the National Portrait Gallery to be searching continuously for angles. Portraiture is, after all, a straightforward affair. Over here you have the artist. Over there you have the sitter. One records the other. And that’s it. Finding inventive ways to present this exchange is, therefore, a museum challenge that encourages much smoking of mirrors.

The problem with the angle attempted by The Encounter is that it isn’t an angle. Every portrait ever produced is the result of an encounter — it’s all a portrait can be. Putting a definite article in front is not enough to give this effort any true purpose or meaning. As for the subtitle, Drawings from Leonardo to Rembrandt, it’s a tease. Neither Leonardo nor Rembrandt is represented here in a significant fashion. If you ignore these directional problems, you are left with a drawing show in which various Old Masters of various levels of talent have been arranged in a string of sections that are supposed to frame telling aspects of Old Master portraiture. But don’t.

We begin with a brilliant Holbein portrait of John Godsalve, a lackey in the court of Henry VIII, who stares into our eyes from across the centuries with that miraculous sense of presence of which Holbein was the master. I’ve been pressed against people on the Tube who felt less real to me than John Godsalve.

Unfortunately, having set this strong agenda, the show switches tack immediately with a selection devoted to Old Master nudes. This is where Leonardo pops up suddenly, with a tiny drawing of a nude man whose head we hardly see because it is squashed against the top of the paper. Instead, the emphasis is on his taut and muscular body, and the heroic way it stands. Having recorded the bulging muscles in red chalk, Leonardo goes over the outlines in ink to give them an idealised clarity.

Superb? Yes. But it’s not a portrait. It’s a heroic study of a nude. The middleweight body is beautifully recorded, but its atmosphere is exemplary rather than human, divine not quotidian, universal not specific. The opposite of Holbein. While we’re at it, why is Dürer also represented among the nudes with a set of illustrations in a book? The one thing I was certain of was that this was a drawing show. Except, it appears, on the occasions when it isn’t.

Having been sidetracked by Renaissance nudes, we lurch next to a section focusing on Annibale Carracci, an artist from the baroque era, 100 years down the art-history road. Carracci ran a famous studio in Bologna. The students at his academy were encouraged to learn from reality by drawing their subjects from life. But the most pertinent thing about the current Carracci contribution, you feel, is that it comes from the drawing gallery at Chatsworth House, which has lent generously to this event. The recurrent impression here is of the tail wagging the dog: of the loans that could be secured planning the journey, rather than the journey planning the loans.

But enough of the cavils. I have made my point. Indeed, I have probably overmade it. The journey may be lousily plotted, but it contains a dozen or so moments of graphic brilliance that make the curatorial confusion forgivable. Back among the nudes, the tiny Leonardo and the printed Dürer are both upstaged by a large Pontormo of a crouched figure picking up a child. The complex pose is madly inventive. The figure itself is snakily strange and elongated. It has little to do with portraiture, but what a thrilling drawing.

And not for nothing was the Carracci academy so well regarded. Another strange nude, this time a bony figure who twists to look at us over his shoulder, seems to record a young man with a physical deformity. His pose is awkward, and so is the intense psychological contact he makes with us. His is a dark, baroque world. Ours is a comfortable, modern one. But somehow a sense of life’s random cruelty is being transmitted across the gap.

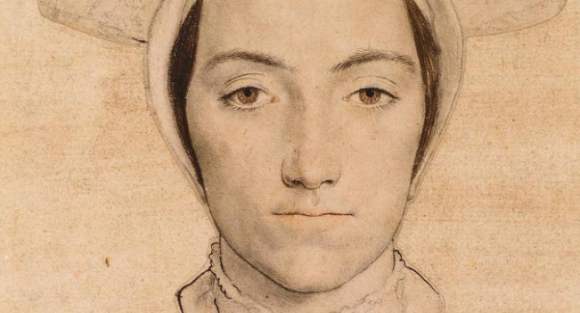

Because the show is so much smaller than we were expecting, we are soon among the royal Holbeins, an exhibition stretch from which all doubts are banished. Holbein’s uncanny ability to capture his sitters’ thought processes — or at least appear to capture them —makes his cast preternaturally present. Out of the Tudor age he yanks them; into our Colgate zone he thrusts them. In front of the man with the black cap, with his bushy beard and his downcast eyes, history ceases to feel like history. In front of the beautiful woman in a white headdress, time ceases to work like time. If she gave me her number, I’d call her. That’s how gorgeously present she is. (Breaking news: the art critic Waldemar Januszczak has been sentenced to beheading for making passionate advances to a lady-in-waiting in the court of Henry VIII.)

When it works like this, portraiture stops feeling like art and starts feeling like magic. And that, I suspect, is what this flawed event is seeking to be about. In matters of portraiture, drawing is a boundary breaker and an equaliser. You don’t have to be a king or a pope or a knight of the realm to be granted immortality by a Rembrandt or a Leonardo or a Carracci. You just have to be at hand when they need someone to pose for them. Pleb or pope, in matters of human tangibility there are no ranks.

At the Ashmolean, in Oxford, another act of important portraiture is being enacted. The gallery has been handed a significant painting by William Dobsonin lieu of tax, and it has now gone on show.

Dobson was the greatest English painter of the baroque age. The Ashmolean’s triple portrait was painted in Oxford during the English Civil War, in 1643 I reckon, and shows three soldiers of the Royalist court in a mysterious show of unity. Two are looking on. The third is dipping his cockade in a glass of wine, as if pledging an allegiance.

The two onlookers are recognisable as Rupert of the Rhine, the king’s nephew and a Royalist hero, and Colonel John Russell, a distant relative of Diana, Princess of Wales. So who’s the third man? The gallery claims it is William Legge, erstwhile governor of Oxford. But the feisty cockade-dipper looks nothing like Legge.

My confident suggestion is that he is William Russell, brother of Colonel John, who changed sides during the war from Roundhead to Royalist. Arriving in Oxford in 1643, William joined Prince Rupert’s troop and fought at Gloucester and Newbury. The portrait must have been painted at exactly the time he switched allegiances. Indeed, that is what Dobson is commemorating: William Russell has grown his hair and is now siding with the king. Rupert hands him his new commission. And John exchanges a look of solidarity with his reformed brother.

Unfortunately, a few months later, William changed his mind again and rejoined the Puritans. But at least an English genius was at hand to record his baroque waverings.

The Encounter, National Portrait Gallery, London WC2, until Oct 22. The Dobson portrait is on permanent display at the Ashmolean, Oxford