The stuckists were protesting outside the Turner prize the other night, as they always do. For a couple of decades now, these sad haunters of the aesthetic shadows have been turning up on Turner night, calling for a return to “proper painting and sculpture”. Every year there are fewer of them, and those who return seem a little sadder. Next year I must remember to take along some 10p coins. The poor sods look as if they could do with a cup of tea.

This time, they have been joined in their wailings by honorary stuckist Michael Gove, who has taken time off from betraying Boris Johnson to betray the process known as civilisation by tweeting opinions on modern art that would shame William McGonagall. Somebody needs to tell Gove that the 19th century is over. He used to be secretary of state for education. He should know these things.

For the whole of my career as an art critic, this same stuck record — “We need to return to proper painting and sculpture” — has been playing on my Dansette. I can usually unhear it. This year it has felt especially piercing. For heaven’s sake, Marcel Duchamp’s first readymade, his spooky bottle rack, dates from before the First World War! Malevich’s Black Square is even earlier: 1913. Art has not been about “proper painting and sculpture” for more than 100 years!

Stuckists, Govists, I beseech you. Nudge forward the record and accept the simple and uncontroversial truth that, for the past century, art has been expanding its range of materials and approaches. These days, “proper painting and sculpture” is one way to make art, but it is no longer the only way. Art always changes. It always will. Is that really such a terrible thing?

As evidence, I bring you two exhibitions. Both can be visited over the Christmas period. One is devoted solely to painting — it’s actually called Painters’ Painters — while the other contains wall hangings made from old T-shirts and a set of sculptures that seem to have been created from stuff found in a skip.

Painters’ Painters, at the Saatchi Gallery, is exactly the kind of show the stuckists clamour for. Nine painters, some of whom work with oil on canvas, others of whom prefer oil on linen, give us 10 galleries of traditional painting. The results are dire, probably the worst show the Saatchi has ever mounted: uninspired, uninspiring, dumb, repetitive and silly.

Meanwhile, at the ICA, New Contemporaries is a selection of student work that ranges from videos to skip art, from performance bhangra to hand-drawn posters, from sculptures made out of plastic swimming rings to films of passing clouds. All kinds of things are being used to make all kinds of art. It’s raw and messy. And because this is student art, it, too, is capable of silliness. But how punchy it is, what energy it brings.

Back at the Saatchi, the hardcore painters work to the kind of rhythm that mill horses used to follow when they clip-clopped round a grindstone. Pervading all their output is an air of frozen effort, as if the pictures have been stored between shows in a fridge. I called this painting “traditional”, but it is never traditional in the welcome sense of the word. No one dazzles you with skill or persuades you with illusionism.

Instead, most of them have chosen painting, you feel, because it is the easiest way to have their say. Bjarne Melgaard, who is Australian, gives us cartoonish heads gurning stupidly above cartoonish bodies. Melgaard is 49. He hasn’t been a real child for four decades. How in Waltzing Matilda’s name has he persuaded himself that painting like a kid in a nursery is a career path worth following?

Even worse is that old Saatchi favourite Martin Maloney. Only the existence of Liam Gillick in Britain’s art orbit stops Maloney from being the nation’s worst artist. Now 55, he still paints as if his mum gave him some oil colours for Christmas. To call his hastily scrawled figures and stiffly reduced faces “childish” is to insult children. My kids were never as determinedly dumb as this.

Unfortunately, Charles Saatchi has always had a weakness for what is optimistically termed Bad Painting; for slacker aesthetics that involve looking deliberately untaught. Practitioners of Bad Painting kid themselves that by releasing whatever dumb nonsense comes into their heads, they are being revolutionary and free. What they are actually being is inept. As a final thought, it pains me to add that most of the work in Painters’ Painters would look perfectly at home in a stuckist exhibition.

Nothing as pointless or sad or limp as the output of Maloney pops up at New Contemporaries. Is there bad art here? Yes, of course. But it is bad because it fails to achieve what it wanted to achieve, not because it set out deliberately to be bad. There’s an honesty at work here that you don’t find at the Saatchi show.

Zarina Muhammad gives us a wobbly homemade video in which she and her bestie dance energetically to “the English beat” while the screen behind them splatters us with images of Middle Eastern jihadis and their exploding bombs. The girls are taking the mickey out of the jihadis, accusing them of glamorised violence. It may be wobbly, but it’s an artwork heavy with wit and courage.

Those messy sculptures made from unglamorous materials that are such an insistent presence in the show — see also Helen Marten, winner of this year’s Turner prize — are a reflection of art’s current preference for authenticity. Over at Damien Hirst’s Newport Street Gallery, the ageing YBA Gavin Turk is showing us chewed-up apple cores and discarded kebab wrappings that are actually expensive bronze casts painted to look like rubbish. But at New Contemporaries, what you see is what is there. When the skip artists Victoria Adam or Rodrigo Red Sandoval combine lowly materials, it is in the hope of engineering flashes of unexpected poetry in their combinations.

The exhibition even includes the work of several painters. And they look thoroughly at home, one method among many. Jack Bodimeade paints electric plugs. James Berrington paints London bricks. The hunt for authenticity has scaled the wall and is scrumping in the orchard of painting. All the painters in New Contemporaries are better, truer and more authentic than their upper-cased opponents at the Saatchi Gallery.

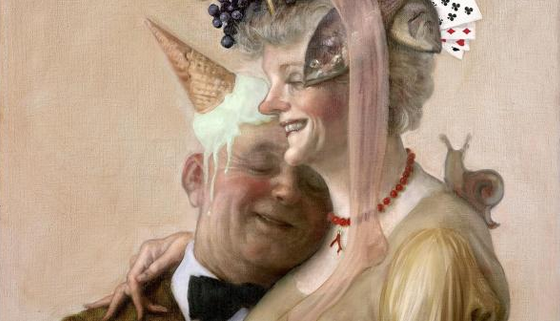

Still on the subject of painting, John Currin, that surreal rococo absurdist — you tell me what to call him! — has a selection of new work at Sadie Coles. It’s a creepy display, as always, and, as always, it appears to combine Old Master techniques with unsettling insights into contemporary America.

As always, it is dominated by portraits, this time of middle-aged couples who all feel as if they have been caught in the middle of a pretence. Look closely at the woman with the see-through top and you’ll see that her teeth are capped and her stomach is bulging behind her leisure pants. The elderly couple who embrace so fondly on a chair would be oozing uncomplicated affection for each other, and nothing else, if he didn’t have an ice-cream cone sticking out of his head and she didn’t have a fish hanging from hers.

It’s satire, but in an especially sly form. American reality is being teased and tickled by a painter who is using the methods of a fly fisherman. Now that’s what I call painting.

Painters’ Painters, Saatchi Gallery, London SW3, until Feb 28; New Contemporaries, ICA, London SW1, until Jan 22; John Currin, Sadie Coles, London W1, until Jan 21