Yves Klein (1928-62) was surprising in various ways, but perhaps the most surprising thing about him was that he was the last significant French artist. Given how much French art achieved in the 16th, 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, and in the first half of the 20th, its disappearance from the front line of global accomplishment in the 1960s is deeply mysterious. One moment it led the world, the next it led no one. What happened to this key artistic nation, and do the achievements of its final big-match player hold some clues?

Actually, I believe they do. A fascinating taster show of Klein’s career that has arrived in Liverpool succeeds both in proving his worth and in making evident what was dubious about him. Klein was an intense presence. His work can sometimes root you to the floor with its beauty. But he also had an absurd sense of his own significance and could not readily distinguish between the profound and the silly. That, I suggest, is French problem number one.

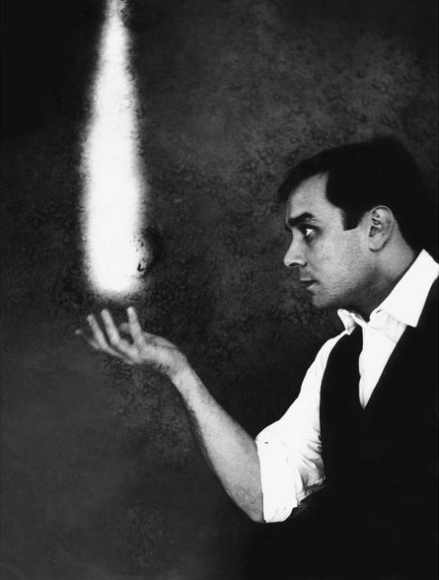

French problem number two is vanity. Ever the showman, Klein gave himself a starring role in his work that was so centripetal, it sits more comfortably in the history of celebrity than it does in the history of art. He had a weakness for himself. And that is something that can be said of the French cock in general in the postwar years.

Born in Nice of artist parents, he trained initially to be a merchant seaman, then studied Oriental languages. In the 1940s, he took up judo, then went to Japan and rose to black belt 4th dan. In 1949, he wrote his first piece of pioneering minimal music, called Monotone Silence Symphony, which consisted of F sharp played for 20 minutes, followed by 20 minutes of silence.

Here, then, was an aesthetic Dodgem car, a wild vehicle of creativity, unrestrained by roads or their rules. When he became an artist, in the early 1950s, he had never been to art school or created a preparatory tranche of juvenilia, though there is a story of the 19-year-old Klein lying on the beach in Nice and signing the sky with his finger as his first artwork. If rules are a bad thing, he was a good thing. If rules are a good thing, he was not. That’s the dilemma.

The first work on view at Tate Liverpool is a cluster of “monochromes”, his first “paintings” from the mid-1950s: small rectangles of colour, orange, green, yellow, pink. It’s brave stuff. For me, they work because they force you into a face-off with something pure and lovely. He may not have had an art training to speak of, but he had an instinct for colour, and there is something utterly precise about the shades he chooses. Somewhere deep inside, the lessons of French impressionism had survived.

With Klein, though, the lovely areas of pure colour had a further and deeper meaning. Or so we are always told in the art-historical mutterings about eastern religions and “the infinite” that invariably accompany every examination of his work. It’s never specific, but it’s always there — a sense that he was seeking something mystic in his art, something learnt alongside the judo in Japan, something Zen-like and transcendent.

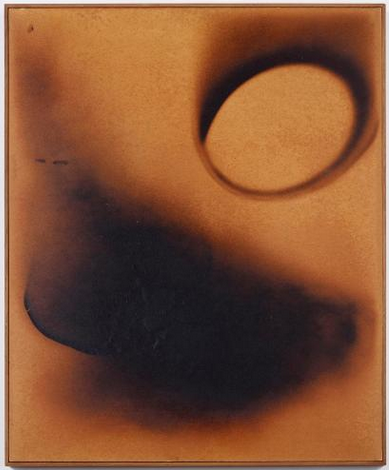

The second room here is devoted to his “fire paintings”, moody black abstractions created by blasting cardboard with a flamethrower. We’ve all gazed into a fire and marvelled at the endlessly interesting glows within. My guess is that this human fondness for the fireside goes back to our beginnings, to the first fires in the first shelters. It’s deeply instinctive, and in his “fire paintings”, Klein is seeking to trap these elusive effects.

Unfortunately, there also exists a set of films of him making the fire paintings, and in them the process is made to look unduly comic. Marching about with a gigantic flamethrower, Klein attacks the canvas like a GI with a bazooka while a pal of his, dressed as a French fireman, hoses down the charred remains. It’s fun to watch in a Buster Keaton-ish way, but it undermines the seriousness of the fire pictures and makes you suspicious of his motives.

Back among the monochromes, having sampled an impressionist’s palette of colours, he decided to focus on a single one, an intense lapis lazuli blue that was to dominate his output from now on. The particular shade of blue he chose is exceptionally beautiful and intense. Staring into large expanses of it is genuinely thrilling. Klein was not the first artist to notice that large expanses of pure pigment have an intoxicating presence, but he was a pioneer in the exploitation of the effect.

Suspending the exciting blue in a chemical formula that did not yellow or crack or fade, he began churning out blue monochromes that have aged superbly and still glow with an exciting intensity. He even gave the shade its own name: International Klein Blue. Branded as such, the simple colour took on an outer identity that was complex and corporate.

That was Klein’s shtick: hiding the simple behind the complex. In an especially sneaky gesture, he mounted a show in Italy of 11 identical blue monochromes, all priced differently, so the buyer ended up paying for the strength of his own experience. Wicked, exploitative, but brilliant!

This conceptual fun is recorded in a strong documentary stratum that gives the show a parallel reality. On the one hand, you have the actual objects — the monochromes, the fire paintings — all of which are simple things, eminently tangible. On the other, you have the conceptual add-ons with which Klein enlarged his artistic presence: the films, the photos, the happenings in which he starred as himself.

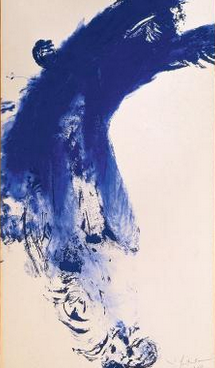

For me, the simple stuff was where he was really at, and the game-playing was the adoption of a disguise. How else to understand his most notorious artistic moment, the production of a set of blobby blue scrawls made by dragging a harem of nude women — “human paintbrushes” — across sheets of paper? Klein called these works his Anthropometries, a weaselly pseudoscientific name for what was evidently an exercise in desire and humiliation.

The film that survives of the Anthropometry happenings shows him striding around in a bow tie and evening jacket while an orchestra plays his Monotone Symphony, and the naked women are painted, splashed and directed like performing seals in a circus. It’s a ghastly event.

But the surviving paintings are not ghastly. They are beautiful and even haunting. Long and low, Anthropometry 56 shows the traces of a full-length figure and feels like the Turin Shroud. Anthropometry 91 is cheekier, a full-on breast print topped with a pink lipstick kiss.

All the dragged blue images refer to something ancient and primitive: a figurative tradition that began in the caves. As always with Klein, however, the updating of the ancient urges involved a pretence that got him noticed, and that turned the work into something it wasn’t.

Yves Klein, Tate Liverpool, until Mar 5