Because it is set in Liverpool, and because Liverpool is such an engrossing location, with so many mysterious corners, the ninth Liverpool Biennial is worth a visit. To see all the shows, I walked 24,367 steps and swung by the old ABC Cinema, both cathedrals, Tate Liverpool, the law courts, the India Buildings, the most derelict street in Toxteth, an underground reservoir with lasers in it, a new fountain by the docks, an old brewery and a square so Stalinesque that it has been used in movies as a stand-in for Moscow. Go to Liverpool for a topographical adventure and you won’t be disappointed. Go for any other reason and you will be.

Ever since it started, in 1998, Britain’s biggest biennale has made the changing face of Liverpool one of its main concerns. I remember trudging to the Catholic cathedral at the first event, and having to pass burnt-out buildings that had survived untouched from the Toxteth riots in 1981. What a grim and plangent experience that was. By the next show, they weren’t there any more.

At every ensuing biennial, Liverpool has looked more prosperous. The Albert Dock has been transformed. The burnt-out buildings have become noisy nightclubs with a fashionably grungy look. If you put them all together, you would get an action-packed flick book of a city on the up.

This year, though, this sense of renewal is absent. Seeing all the displays still involves tracking down derelict buildings and exploring them (a former sawmill, the Cains brewery), but the investigative aspect of old has been replaced by impulses that feel voyeuristic. On the press day, we were bussed to Toxteth, where a street of identical terraced houses — all boarded up, with notices on them warning of the consequences of breaking in — provided the backcloth for a monumental stone slab by Lara Favaretto that had been dropped in the centre of the decay like a giant dolmen. Watching the London art world cooing at the symmetry of the dereliction like a gang of sightseers on an open-top tour was grotesque.

So the story of Britain’s biggest biennale is the story of a growing disconnect between a city and its show. To make it all worse, this year’s theme feels especially pretentious. The event always has a thrust — an organising plan. The latest one involves taking us through a series of experiences that the biennial bods have dubbed “episodes”. There are six of these episodes in all. I suppose I had better list them for you, though it won’t help much. They are: Ancient Greece, Chinatown, Children’s Episode, Monuments from the Future, Flashback and Software.

Of course, getting down with the kids is a classic ingratiation strategy. And an easy way to circumvent adult judgments. In this instance, it is made worse by the baseness of the deceit. The Liverpool kids dress up. They have fun. They run around on cue. Meanwhile, a ringmaster from the London art world steals their happiness and turns it into biennale fodder.

The most tangible display for the Ancient Greece episode is at Tate Liverpool, where a selection of “Greek” artefacts has been mixed in with some new works by international artists. According to the biennial bumf, the episode takes its cue from those 19th-century buildings in Liverpool that set out to look like bits of the Parthenon. But the resulting show has no architecture in it. Instead, we get classical pots and bits of sculpture drawn from the notoriously unreliable Blundell collection at Liverpool’s World Museum.

The Blundell collection is notorious because it contains so little that is actually Greek. Not only are the sculptures doctored — the poor hermaphrodite in the Tate foyer has had his member sawn off, turning him/her into a sleeping Aphrodite — but several of the pieces are originally Roman. Worse still, most of Blundell’s statues have been assembled from bits of other statues, creating a Frankenstein art that looks vaguely classical, but isn’t.

The Tate selection reacts to this ancient disorder by commissioning fresh disorder from contemporary artists. Thus, the busy Middle Eastern threesome of Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh and Hesam Rahmanian have created a post-Greek Ganesh, on which an elephant’s head is attached to Aphrodite’s body. At the back, Betty Woodman gives us a mural of a chic domestic interior decorated with Aztec pots. Out of the solid notion of Ancient Greece, this absurd event has managed to create a fog of multicultural serendipity.

The best thing about the Chinatown episode is that it is set in various restaurants in Liverpool’s Chinatown. To see Elena Narbutaite’s photos of a woman swimming in a leopard-print swimsuit, you have to go into the ladies’ loo at Mr Chilli. While at the Master Chef restaurant, Ana Jotta has painted pale green abstracts in which “the colours are reminiscent of antique green pottery that the artist saw in a magazine while on her train to Liverpool”. So she really bust a gut there.

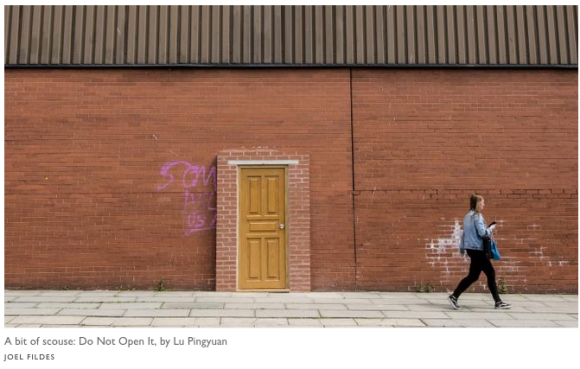

As I said, at least you get to see the city. At Exchange Flags, the imposing city square that has been used in movies as a stand-in for New York and Moscow, Sahej Rahal has erected a pile of rusting girders as his contribution to the Monuments from the Future episode. In a brick wall around the corner from the Cains brewery, Lu Pingyuan has inserted a door that leads nowhere. Perhaps the show could adopt it as its logo?

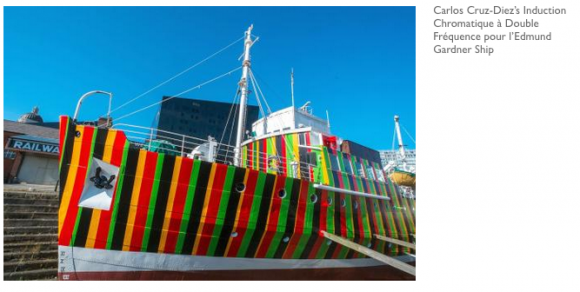

While the biennial proper ties itself into ghastly knots trying to keep up with the themes imposed on it by the curatorial faculty that organised it — that really is what they call themselves — it is left to the peripheral events to bring some uncomplicated pertinence to these proceedings. The sight of Peter Blake’s camouflaged ferry bobbing about in the Mersey, a survivor from earlier celebrations, is always cheering. And the John Moores exhibition, Britain’s leading painting prize, housed as always at the Walker Art Gallery, has another strong year.

The best of the satellite shows is Bloomberg New Contemporaries, at the Bluecoat gallery. Thank God. It’s good news because New Contemporaries is a selection of the best student work being made in Britain’s art colleges, so it’s a show that points to the future. Selected by a trio of artists, rather than a curatorial faculty, and elegantly installed in a suite of lofty galleries that make a pleasant change from the dripping underworld in which the biennial is chiefly set, New Contemporaries finally presents something clear and focused.

Especially evident is the emergence of a type of sculpture that makes inventive use of grungy materials. Harry Fletcher gives us an inflatable swimming aid poised dangerously between concrete nails. Leah Carless has something lumpy and snaky hanging from the ceiling, suspended on see-through bra straps. Rodrigo Red Sandoval creates a homemade cosmos out of floor dust and bits of satellite dishes.

This grungy sculpture says things to your instincts. It’s the visual equivalent of running a fingernail across a blackboard. It wakes up the senses and readies them for flashes of poetry. Hurrah. Students to the rescue.

The Liverpool Biennial runs until Oct 16; biennial.com