“Performative” is a new word in art. I have been an art critic for several decades and have never previously had cause to type it. My copy of the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary doesn’t even have it in. It appears in my Collins, but only in the following terrifying form: “adj. linguistics, philosophy. 1.a. denoting an utterance that constitutes some act, esp. the act described by the verb.” Which means… er… well you know what it means.

Performative is not, therefore, a word you might have expected to find peppering every page of a Tate Modern catalogue, as well as most of the gallery walls. But there it is. Everywhere. Even Chris Dercon, the outgoing Tate director, who’s Belgian, for heaven’s sake, and has no right to know more English words than I do, uses it brazenly in his introduction to Performing for the Camera, the confusing but engrossing examination of the relationship between the camera and performance art that his gallery has now mounted. “Since the 19th century,” Dercon explains, “the performative potential of the photograph has been a vital medium for artists.” Damn. How did I manage to miss it?

In truth, this clunky piece of art-world jargon, borrowed from the bleak well of poststructural linguistics in an effort to make art sound more scientifically grounded than it is, has come to mean something simple and even banal. Any photograph that shows an artist doing something for the camera can be called a performative photo. As a slice of artistic territory, it is almost bottomless. And Tate Modern has done well to find any kind of route through this barely discernible terrain.

Why have they bothered? That’s easy. Performance art is uber-fashionable on the biennale circuit. Across curatordom, the 1960s are on rewind, and happenings are happening again. More pertinently, Tate Modern’s £260m extension, due to open in June, is going to be focused largely on performance art. It has to be. Tate has nothing else to put in it! The current building has more than enough space to house the existing collection.

Bankside is, therefore, reinventing itself as a site of transitory excitements and noisy one-offs. Which is where Performing for the Camera comes in. How can you ensure the longevity of a transitory moment? If something is over, how can it remain active? Performing for the Camera is seeking to supply art-historical ballast for the creation of something out of nothing.

Perhaps that’s why we begin with Yves Klein’s Leap into the Void? This famous performative photograph from 1960 shows the artist jumping off a wall, seemingly diving to his destruction. It works because the image is poised at a moment of unavoidable danger and forces you to imagine what happens next. Cracked spine? Broken head? In fact, the scene was fabricated — spliced together from separate photos that are helpfully included as well. One shows Klein jumping into a safety net. The other reveals the empty street. The performative dive never happened. Thus, a twisty agenda gets twistier still on its first wall. The only record of Klein’s leap is the photo, which turns a brief happening into a recorded event. But the brief happening never happened, the photo is faked. So what exhibition path are we being prompted to follow?

Starting with Klein is a high-risk strategy. He was Frenchly expert at disguising conceptual rigour with dodgy showmanship. Or was it the other way round? For his next trick of 1960, he mounted an infamous happening in which naked female models dipped themselves in blue paint and pressed themselves onto blank canvases, leaving behind blobby imprints of their bulges. Klein himself, in a tuxedo, walked around instructing them like a lion tamer in a circus.

As if to vaccinate these rococo happenings against accusations of sleaze, he christened them his “Anthropométries”. Which is like a strip club calling itself Dilated Discalceation. That said, the camera’s ability to find lasting drama in the temporary moment, and even to deepen it, is something to note and celebrate. Charles Ray’s Plank Piece, also in the first room, shows the artist draped across a plank propped against a wall. That’s it. But it works because what’s being choreographed here is a sense of imminent collapse. The camera has made permanent a fleeting drama.

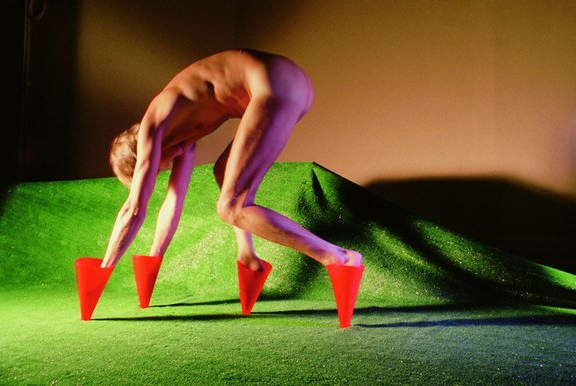

Ray turns out to be unusual in keeping his clothes on. Yayoi Kusama’s hilarious 1960s flag-burnings and antiwar stagings are enacted by teams of discalced New Yorkers desperate to flash their bits at the world’s problems. Boris Mikhailov, the great Ukrainian recorder of post-communist squalor, pops up most surprisingly as a nude action dancer, leaping around a grubby stage brandishing a dildo. A couple of walls later, the same veiny prop is waved at us by the nude Lynda Benglis, protesting against the macho leanings of the New York art world.

Few of the sections into which the show is now divided are as purposeful or as clear. Having proved that the camera can make something lasting of the disposable moment, the event does a Boris and wavers like a shopping trolley. Among the more tangible collections is a gallery devoted to artists who have used the camera to create exaggerated versions of themselves. Warhol, Beuys, Koons were all guilty of performative enlargement.

It’s noticeable, too, that the original happenings usually had global and political ambitions — to stop the war in Vietnam; to stop the World’s Fair in Japan — while the recent ones are invariably turned inwards, towards the artist. In the age of the selfie, everyone stares at the navel, no one looks at the navy.

Having billed itself as a survey of 150 years of performative photography, the exhibition also attempts darts into a deeper past by including Nadar, who in 1854 gave us a prancing Pierrot gurning at the camera. He’s supposed to prefigure the fierce identity swaps of the 1970s and 1980s — Cindy Sherman, David Lamelas, Hannah Wilke — but in his grainy salt prints, the action is too distant to pack a psychological punch.

The display is best enjoyed as a selection of disparate and often fascinating tussles between artists and cameras. There is much I have not seen before, particularly the fascinating Japanese performance photography unearthed in the searches.

Tokyo Rumando makes something Hitchcocky and tense out of her face’s dark appearances in a mirror. Tomoko Sawada, meanwhile, dresses up as 100 different people, then records the transformations in a photo booth, whose gifts to the new personas are ordinariness and banality. The Japanese self and the camera seem to have an especially relaxed performative relationship.

Performing for the Camera, Tate Modern, London SE1, until June 12