Which British gallery has successfully halved its impact by doubling its size? The answer, unfortunately, is the Serpentine. Ever since the so-called Serpentine Sackler was opened in 2013, on the other side of the bridge from the old Serpentine in Kensington Gardens, the straightforward task of visiting here has become complicated. Is this one gallery or two? Do I need to see both shows? Can I be arsed to walk across the bridge?

Alongside these casual binary difficulties, the exhibition programme has also been uninspiring. A couple of standout events — Marina Abramovic, the Chapman brothers — have been outnumbered by a haze of low-impact displays ordered from dial-a-biennale. The feeling persists that instead of making brave decisions in the studios of British artists, Serpentine curators prefer to scoot between Istanbul and Sao Paolo. If you missed something at the Venice Biennale, don’t worry. It will turn up six months later at the Serpentine. As a result, the gallery’s identity has blurred. Visitor numbers have been disappointing. A must-go venue has become two might-go venues.

That’s the bad news. The good news is that the gallery/galleries is/are still capable of occasionally making light of the inherent difficulties it/they has/have visited upon itself/themselves by coming up with a smart combination of shows. Which is what has happened with Lynette Yiadom-Boakye on one side of the bridge, and Duane Hanson on the other.

Yiadom-Boakye is a marvellous force for good that has emerged in British painting. Born in London of Ghanaian parents, she is the first figurative painter I have seen who has made blackness her flagship colour. Abstract painters have done it before — Malevich, Soulages, Kline — but their work was an exploration of the universal. As a black woman, Yiadom-Boakye has a more visceral and personal relationship with her subject.

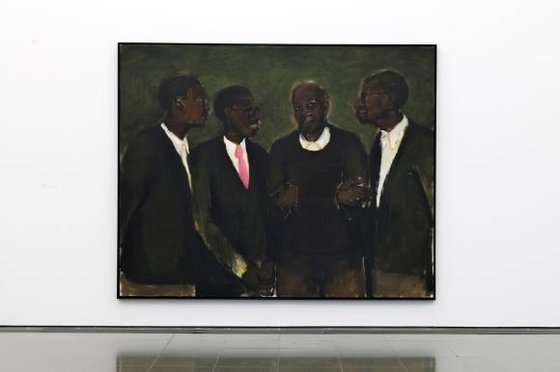

It’s clear from the off that she’s interested in blackness as a pictorial challenge, a colorific condition, rather than a key to identity. The show is full of black faces, mostly of young men, seen against dark backgrounds, as if she were setting herself a test. In Highriser, a tall gesticulating figure wearing a black jumper and blue slacks strides towards you out of a deep nightscape. In A Bounty Left Unpaid, a young man crosses a river at twilight, jumping from rock to rock. His shirt and socks are white, so the surrounding darkness plays interesting games with his strobing outline as he jumps.

All this is new. Plenty of painters have previously observed how colours behave differently in subfusc conditions (Manet, Caravaggio, Elsheimer), but none with the special interest of Yiadom-Boakye. New conditions encourage new insights. In the twilight, the blue slacks worn by the man in Highriser have a shiny black-purple depth to them that I do not recall seeing in a painting before. White behaves differently, too. In most Yiadom-Boakye faces, the focus shifts pointedly from the pupils of the eyes to the whites.

Given how long painters have been painting, how amazing that no one I can think of has previously explored any of this. In the show’s most exhilarating pairing, two dancing women in black are hung next to two dancing women in white. Both are swirling around the dancefloor, yet they seem to swirl at different speeds. Elsewhere, in a picture that seems to look out at you, instead of you looking at it, a chap in a stripy black and white jumper seems to have been taught how to make a sartorial impact by a zebra.

The results of all this pioneering colorific exploration are mysterious, haunting and beautiful. Although the paintings have a presence that seems more poetical than political, they seem also to carry a social weight: a sense of historical sadness. No one anywhere specifically mentions slavery or displacement, but the room keeps whispering the words.

It’s a sensation made most explicit by a painting of a typically handsome black face looming up beside a particularly bright scarlet macaw. You don’t have to have read Robinson Crusoe to sense what a loaded comparison is being made here between two types of exoticism — the full colour and the subfusc.

Across the bridge, in the other Serpentine, the American realist Duane Hanson is being treated to a welcome revisit. Since his death in 1996, his reputation has been lost down the back of the sofa. Which is unfair, because his realism was never as dumb and disposable as it appeared to be.

His stock in trade is the life-sized single figure, so perfectly convincing in all its details — clothes, hair, veins, skin texture — that when you come across it in a gallery, it scrambles your senses. Your brain knows you’re looking at a waxwork. But your eyes are reluctant to accept it. Try leaning into the Colgate zone of a Hanson sculpture and you’ll feel exactly as you feel when you lean too close to a stranger on a bus. It’s transgressive and unsettling.

Where the waxworks you find at Madame Tussauds are doppelgangers of celebrities and important historical figures, Hanson’s stand-ins are drawn deliberately from the ranks of the everyday. Two obese tourists on a bench. A scruffy house painter in overalls, painting the walls of the gallery pink. A glum delivery guy with a trolley. A kid in a pram. If you passed them in the street, you wouldn’t give them a second look. But this isn’t the street. This is the posh new Serpentine Sackler, where anyone below the rank of garden-party invitee is made to feel underdressed.

One thing that is certainly being proved here is that reality has its own spooky magic. Plucked out of the Niagara Falls of daily life, even the dullest presence becomes fascinating. Like the pop artists before him, Hanson was interested in nondescript America precisely because it wasn’t nondescript. Not when you looked at it this closely. The dumpy Flea Market Lady surrounded by the things she’s trying to flog ought to be reading National Enquirer. Instead, she’s flicking through the pages of Artforum. The Cowboy leaning against the wall is dressed for the rodeo. But his downcast eyes examine the ground as glumly as a man who has just been told he has cancer.

Unable to respond or interact, trapped in their own likeness, Hanson’s unhappy waxworks have been frozen in a state of perpetual alienation. No one here is lucky. No one here is free. After a couple of circuits of the gallery, the moroseness becomes more insistent than the reality.

At the Timothy Taylor Gallery, a group of paintings by another notorious American naysayer, Philip Guston, has gone on show. Where Hanson notes the sadness of modern America, Guston enjoys its squalor. Smoking too much. Drinking too much. Eating too much. Sleeping too much. If a happy pig could paint, it would paint like this.

Lynette Yoakim-Boakye and Duane Hanson, Serpentine Gallery, London W2, until Sept 13; Philip Guston, Timothy Taylor Gallery, London W1, until July 11