On the face of it, the two shows I am writing about this week have nothing in common. Indeed, their differences are striking. Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s photographs at the Hepworth Wakefield are separated from The Great War in Portraits, at the National Portrait Gallery, in London, by a lot more than 184 miles. Tonally, they may as well be on different planets. DiCorcia is “one of America’s most important and influential contemporary photographers”, whose work gets gobbled up at art fairs and biennales. The Great War, meanwhile, is a scar from another century that can never heal: an immovable reminder of the pointlessness of death. Two entirely different shows. What unites them?

The answer is “reality”, or, more specifically, “the appearance of reality”. Both these events are concerned with art’s power to evoke reality and tinker with it. Both warn us, therefore, to doubt what we are shown.

DiCorcia’s sneaky photographs of people and places are never quite what they seem. He works in clusters of linked images, and the Wakefield show sets out to encapsulate his career so far by flicking back through the best-known of these series. Interestingly, this encapsulation is done in reverse. The journey starts with his latest works, then winds back through his career to the first notable pictures he took, in 1975. The thinking behind this unusual arrangement is, I imagine, to prompt a different reading of the early work by approaching it through the late work. In particular, showing his career this way round makes clearer his slippery relationship with reality.

His latest series, the one we start with, is called East of Eden: a portentous title with biblical connotations. At first sight, however, the photographs themselves seem neither portentous nor biblical. A woman stands under a tree. A cowboy rides across a valley. A wooden bungalow in the snow has an American flag outside it. A tree is filled with apples. The pictures are big and pretty, but not immediately weighty. It takes a moment’s puzzling to work out their biblical plot lines.

The woman under the tree, statuesque and beautiful in the glowing evening sun, is Eve. The tree filled with apples is the Tree of Knowledge. The bungalow in the snow is Noah’s Ark after the Flood. And the chap throwing a dart at the young boy standing in a garage is Abraham preparing to sacrifice Isaac. Or, rather, he’s a contemporary stand-in, acting out a photographic approximation of Abraham’s story: diCorcia is using modern America to recreate the tumultuous biblical events described in the Book of Genesis.

So that’s us warned. For the rest of the show — the journey back to the beginning of his career — we understand that the ordinary realities he appears to record are not ordinary realities. In the series Streetwork, what seem to be everyday crowd scenes, photographed in cities including New York, Paris and Mexico City, are carefully staged moments of urban drama, rehearsed on Polaroid and practised beforehand with an assistant. Only when the perfect camera position has been found, and the perfect lighting achieved with banks of hidden flashes, is the general public allowed into the photograph to complete it.

The series known as Heads takes the process a step further by singling out and lighting a particular individual in the crowd. The special lighting doesn’t just select them, it seems also to sanctify them, in the way a halo picks out the saint in a Renaissance painting. The results are mysterious and marvellous, diCorcia’s best work.

All this is so good it makes what comes next — what came before! — look piddly in comparison. The show ends at the beginning of diCorcia’s career, with an extra-long series of 76 small photographs, called The Storybook Life, in which he flits from people to places and unveils the assortment of reality-testing strategies we see perfected at the other end of the show. Smaller, humbler, less technically flashy, less dramatic and less memorable, the modest photography of The Storybook Life is so successfully ordinary that it convinced me entirely of its ordinariness.

Nothing as convoluted happens in the National Portrait Gallery’s powerful telling of the story of the First World War through portraiture. This simple but effective strategy achieves two things. First, it makes the conflict tangible by putting faces to the statistics. Second, it clouts us about the heart and forces us to feel the unforgivable tragedy of it all. Portraiture personalises everything and makes abstraction impossible. By matching faces to names, likenesses to reputations, this punchy event plucks the Great War out of the history books and pushes it into our intimacy zone. Brilliantly curated, it had me sobbing all the way up the Charing Cross Road.

The first guilty parties brought to life are the chaotic European royals whose ungodly squabbling led ultimately to 10m unnecessary deaths. We spot them initially in 1910, assembled in England for the funeral of Edward VII. Within four years, these same arrogantly disturbed cousins and uncles were ordering their armies to slaughter each other.

Franz Josef of Austria looks every inch the demented despot who believed in the divine right of kings. George V and his cousin, Tsar Nicholas II, are all but indistinguishable, so strong is their family likeness. George V’s other cousin, Kaiser Wilhelm II, the most unbalanced of them all, hides his withered arm in a big military sleeve, puffs out his chest and pretends he’s made of the stuff of warriors.

The display makes obvious how the kings and the generals used portraiture to enlarge their reputations. The ordinary soldiers, meanwhile, the ones actually doing the fighting, lend their faces to the show, but remain unnamed. At the centre of the remembrance is a wall packed, floor to ceiling, with exceptions — from Siegfried Sassoon to Wilfred Owen, from Baron von Richthofen to Walter Tull, the first soldier of Afro-Caribbean heritage to become an officer. All of them stare out at you and challenge you to count them.

Hardly any of the portraits attempt much in the way of progressiveness. It’s as if modernity and artistic ambition were suddenly deemed inappropriate. The only artist to get a decent airing is William Orpen, whose calm and conventional portraiture keeps popping up, and seems always to maintain a stiff upper lip.

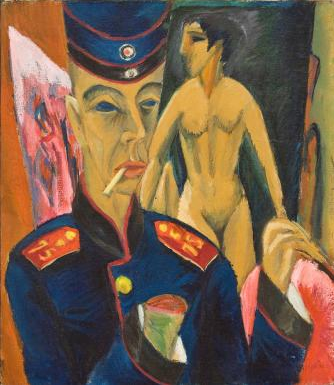

This careful calmness is a feature of the entire show. It only disappears at the very end, when Henry Tonks begins drawing harrowing portraits of the soldiers who had their faces blown up at the Somme, and who needed plastic surgery. Perversely, the best art of the conflict was produced by the other side: by the German expressionists, represented here by a jagged Kirchner self-portrait from 1915, in which he imagines himself with his hand blown off.

After all the pretence and preening, the positioning and role-playing, here at last is art with a simple ambition: to capture the true and terrible spirit of the war.