The full scale and depth of an artist’s achievement can take time to grow obvious. Yes, you get noisy geniuses who are never anything other than a noisy genius. But you can count those artists on two fingers: Picasso and Michelangelo. The other giants of art grew more slowly to their eventual size. And to this second group, I now feel, on the strength of the mightily impressive look back across his career that has opened at Tate Modern, we should add Richard Hamilton (1922-2011).

No, I’m not saying Hamilton is up there with the Picassos and Michelangelos. But I would now place him just a couple of rungs down the ladder. Certainly, he was Britain’s most important artist of the postwar years. Certainly, his example changed the course of British art and gave it a future.

A particularly impressive aspect of this engrossing Tate event is its constant sense of change. Hamilton was always experimenting. The first room here is such a surprise. It features an exact re-creation of an exhibition called Growth and Form, mounted at the ICA in 1951. We’ve always known Hamilton was supposed to have invented pop art — it’s one of the few givens about him — but who suspected he was a pioneering natural-history enthusiast?

Growth and Form was a room-wide investigation of nature’s vacillation between structures and blobs, molecules and amoebae. Over here: a glass case full of birds’ eggs. Over there: a test tube bubbling scientifically. In front of you: a white modular framework sitting on the floor. Behind you: an octopus in a light box. Nowadays, we’d call this an installation. At the time, installations were not supposed to have been invented.

Frankly, I could spend the rest of this article discussing all the developments predicted by Growth and Form. From installations to Damien Hirst, from video art to geek art, from minimalism to, believe it or not, the taxidermy craze. Even the way Tate Modern is laid out — thematically, with an emphasis on blundering investigation — is being foretold.

What Hamilton had from the start, and what the other giants of his era — Bacon, Moore — did not, was an understanding of the modern world: its rhythms, textures, thrusts. But he was also less of a celebrator than we usually imagine. Growth and Form is saying something big about Britain’s postwar state: the destruction of the old certainties; the return to a molecular ground zero; the essential meaninglessness of it all. As this show goes on to reveal, lurking beneath Hamilton’s sexy surfaces, there was usually a dark underpinning of nihilism.

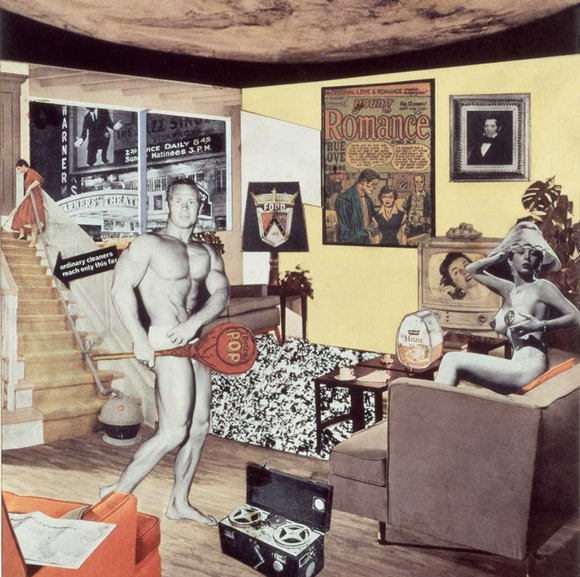

It’s even true of his pop art. It, too, was tinged with sarcasm. Your standard modern-art textbook will tell you British pop art differed from the American variety in being driven by intense transatlantic yearnings: we wanted the cars and the Coke bottles, but they were over there, not over here. The Tate show picks expertly through various aspects of Hamilton’s pioneering pop phase and, joy of joys, actually includes a full-size re-creation of the famously significant This Is Tomorrow installation that he mounted at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1956.

You can walk through this celebrated piece of artistic futurology, noting not only the prescience that saw Hamilton making art about Marilyn Monroe and Marlon Brando, jukeboxes and beer bottles, a decade before Warhol, but also the sense of send-up that frames the little green men who are also included, and the wonky spaceships in which they fly. There was much about Hamilton that was astonishingly modern, but in his mocking of America’s Cold War dumbness, he was old-school and European.

Also impressive are the pale paintings he continued to produce in these fertile years. A beautiful abstraction from 1950, called Chromatic Spiral, is as much about the spaces between the shapes as it is about the shapes themselves: imagine a box of nails emptied onto snow.

During the war, he had been a technical draughtsman, and a taste for tiny moments of accuracy set in lots of white paper continued into his painting. Even when the pop imagery starts creeping in, it has such a fragmentary presence. You never see the full car, the full girl, the full fridge: just desirable bits of them, scattered about the whiteness, as if a concrete poet had taken up painting.

All this time, he was also a teacher at Newcastle School of Art, and one of the modules from which this display is assembled celebrates his pioneering support for Marcel Duchamp. These days, for better or for worse, Duchamp is recognised as a crucial influence on conceptual art. If you want to know how that influence affected Newcastle first, then the rest of contemporary art, it’s made clear here: Hamilton was to blame.

As if inventing pop art and conceptual art were not enough, he also played a seminal role in the history of neo-geo. Remember the exquisite product displays of Haim Steinbach, Ashley Bickerton, Jeff Koons? They are all prefigured by Hamilton’s fetishistic obsession with the sleek silver presence of the Braun toaster.

This whole show has a relentless sense of invention about it: it just gets better and better. By employing new methods of printing, computing, visualisation, Hamilton kept pushing British art into fresh, modern territories. And what a marvellous generosity there was to his civilisational world-view. You cannot imagine Henry Moore ever deigning to design a cover for a pop record. But there was Hamilton, in 1968, lavishing more of his trademark paleness on the Beatles’ White Album.

Another of his most famous works is that curiously powerful image from 1968 of Mick Jagger and Robert Fraser handcuffed together in the back of a car. An inconsequential newspaper snap of a drive to court has been turned into a powerful encapsulation of the spirit of Swinging London.

Round about 1970, there was a big shift in Hamilton’s tone. Until then, his politics had largely remained disguised. Suddenly, they become explicit. From 1970 until his death, much of his artistic energy was devoted to mocking the antics of our leaders: Hamilton, it turns out, was a bit of a Hogarth.

Thus, a television image of an overbearing Margaret Thatcher lecturing her audience on the need for austerity looms up over an empty bed in an empty NHS ward. A few wars later, Tony Blair is given a fearful slapping in a darkly hilarious image of him presiding over the invasion of Iraq in his best cowboy gear: Two-Gun Tony, the fastest draw in the west of London.

Having all this near the end of the show has the effect of adding retrospective weight and meaning to the beginning. Hamilton, we are encouraged to remember, was a signed-up Ban the Bomber, whose career began in a world threatened with atomic destruction. Nihilism was his generational inheritance. So he wasn’t really that different from Bacon after all. Not on the molecular level. See this show. It’s brilliant and important.