I am not sure whether the Serpentine Galleries really knew what it was letting itself in for when it invited the Chapman brothers to take over its elegant new space in Kensington Gardens — the one designed by Zaha Hadid. The Serpentine is a refined and exquisite location that seems whiter than most galleries: cleaner, posher, better connected. If you are an art-loving princess and need somewhere to throw a garden party, you approach the Serpentine. The arrival of the Chapmans at such a location is like a takeover of the playing courts at Wimbledon by gypsies.

What a chaotic first impression this show makes. If there is an organising principle at work here, it’s the kind favoured by the organisers of a car boot sale. “Wot you sellin’, guv? Giant vitrine filled wiv Nazis? Plonk it down ’ere, next to the work bench covered in human brains. Wot’s that, then? Taxidermy from the children’s open day, wiv a fox rogering a rabbit and a rabbit rogering a rat and a rat rogering a mouse? That goes ’ere, in the kids’ biology section. And the crucified McDonald’s hamburger — put it there wiv the rest of the religious tat.” It’s grotesque, primitive, childish. And, reader, I’m lovin’ it.

You could easily spend an entire day rummaging among the countless drawings, sculptures, paintings, defaced books, anti-McDonald’s tapestries, films, installations, cooking displays and life-size mannequins — 36 of them, dressed as members of the Ku Klux Klan — that make up Come and See, the particularly disrespectful, and particularly brilliant, mini retrospective by the Chapmans. The show does lots of things, one of which is to mount an assault on that air of minimalist sanctity you get in typical white cubes. Yes, there’s plenty here that doesn’t work. But, more significantly, there’s plenty that does.

It’s clearer, too, than it has been at previous Chapman events that the real subject of their art isn’t their busy creativity, but ours. See that brutality, that infantilisation, that despoliation and desecration, that endless warfare, that emotional nihilism, that bottomless corruption — that’s us. It was the Jewish historian Hannah Arendt who coined the phrase “the banality of evil”. She was sent to Jerusalem by The New Yorker in 1961 to report on the trial of Adolf Eichmann and was struck by his unexpected ordinariness. The explanations he offered for the gassing of the Jews were neither dramatic nor demonic. Instead, they appeared, in Arendt’s searing adjective, “thoughtless”.

This idea that evil is the achievement not of fire-breathing demons, but of ordinary folk who aren’t thinking, seems to me to be what much of the Chapmans’ art is about. They rope in the Nazis at every step for Arendt-type reasons. Like their hero, Goya, they see evil everywhere. In Ronald McDonald. On the walls of children’s nurseries. In our ruination of nature. In our taste for “light entertainment”. From the moment I saw the four black banners that greet you — decorated with smiley faces, but arranged like swastikas at a Nuremberg rally — the phrase “the banality of evil” entered my thoughts and stayed there.

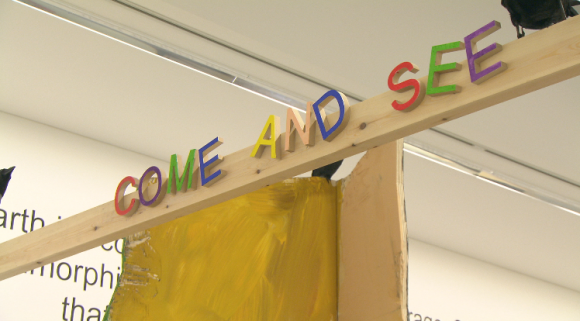

As for the title, Come and See — an echo of Elem Klimov’s harrowing film about Hitler’s invasion of Russia? — which is repeated here on a knocked-up wooden arch between some bunting, as if it were the greeting at a village fete in an episode of Midsomer Murders: never have I seen three sinister words feign this much innocence. Except, of course, at Auschwitz, where the sign over the gate says Arbeit Macht Frei — Work Makes You Free.

The most impressive exhibits in the overcrowded display that follows are the glass cases filled with scenes of mass carnage and cruelty perpetrated, in the main, by endless battalions of miniature Nazis. They rape, they sodomise, they crucify. As Arendt understood it, every one of them is potentially every one of us. To amplify that point, dotted about the show are the 36 life-sized hooded figures dressed as members of the Ku Klux Klan, who wander about the exhibits and peer into them with typical gallery-goer curiosity. They ought to be sinister, but they’re actually rather comic. Their grubby white gowns are too soiled to be properly sinister — “Eva, could you put my Klan clothes in the washer? There’s a meeting tomorrow.” “Wash them yourself, Adolf. I’ve got cheerleader rehearsals.” If you look down at their feet, you will see they are all wearing Peruvian rainbow socks, with sandals! Beneath the Ku Klux Klan outfits, they are just typical sandal-wearing gallery folk, like the rest of us.

One of the best things about the Chapmans is their hardcore work ethic. The show includes half a dozen of their brilliant Nazi death-camp vitrines, and the amount of effort and invention that has gone into each glass case is staggering. Having lost their first Nazi tableau masterpiece, Hell, in the Momart fire, they have since gone on to produce three more, each one taking four years to complete. By using zillions of toy Nazis to construct their scenes of terror, the Chapmans mix a note of unsettling Hamleys innocence into them. Then they add the sense of instructive live overview you get with an ant farm. Finally, there’s the sheer horror — the banal horror — of those glass cases you see in Auschwitz, filled with mountainous heaps of shoes and hair and spectacles.

The result isn’t just the most eloquent war art of our times. It’s some of the most eloquent war art ever made. Why has the Tate not purchased several roomfuls of these harsh and brilliant vitrines? They are our era’s masterpieces.

Nor does the show end there. In fact, there’s tons of it left. A hilarious installation called Shitrospective presents the best-known pieces from the Chapmans’ back catalogue as wonky cardboard models of the sort kids are encouraged to make in art classes. Children — or, rather, what we do to them — are a recurring theme. Poor Ronald McDonald comes in for a fearsome artistic crunching. A particularly hellish vitrine featuring an army of crucified Ronalds is merely the most savage attack. When the Chapmans are around, one thing you do not want to be is a banal corporate freebie aimed at kids.

Another standout set of exhibits features a set of Victorian portraits that the brothers have “improved” by adding horrible skin diseases, disfiguring scars, suppurating sores and protruding eyes. Once again, ordinary human presences have spewed up some extraordinary human rottenness.

With their wicked humour, their work ethic, their spectacular untamability, their Goya-like fearlessness and their mad inventiveness, the Chapmans are now Britain’s most important artists.