The death of Lou Reed in October was one of those rare musical deaths that feel genuinely profound: as if they mark out time. Elvis’s was another one. So was John Lennon’s. In Reed’s case, the level of international dismay that greeted the news of his passing was rather surprising. Considering he only had one proper hit record — the lugubrious Walk on the Wild Side, which got to number 10 in the British charts in 1973 — how exactly had he managed to become such a musical giant? Where had all this Lou-love been hiding?

One of the good things about Mick Wall’s Lou Reed, a biography rushed out with indecent haste for the Christmas market, is that it answers these questions without trying to. Wall, a seasoned rock writer with four decades of service in the court of the record company, confesses from the off that he is a Reed man, and nowhere in the 233 furious pages that follow does he leave you in any doubt that you are reading the outpourings of a besotted fan.

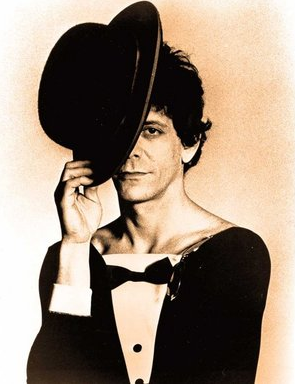

The Reed we find here is straight off the album cover — shades, leather jacket, bisexual, smart-talking, rude to journalists, cruising the streets of Manhattan on his motorbike, doping himself senseless and beating up his first wife. That is also, you feel, the Reed with whom Wall is besotted. It is not, of course, the real Lou Reed. He won’t appear until a more objective biography is written further down the line.

In the meantime, this “sincere speed-written, blood-spattered tribute” strings together the raciest anecdotes from the Reed section of the cuttings library, and does it rather well. He was born in Brooklyn in 1942 to a high-flying Jewish tax accountant, and a former beauty queen. When Lou (real name Lewis) was 17, his father — alerted by signs of fledgling homosexuality — had him confined to a psychiatric hospital where they gave him electric shocks, three times a week, to make him straight. It didn’t work. But it did affect his co-ordination, and for the rest of his life Reed never managed to write his signature the same way twice.

These bad-dad stories about the early days are well known, and could do with some enlargement. Until then, we are stuck with a classic father-doesn’t-understand-son thumbnail that pictures the son picking up a guitar and going off the rails. At Syracuse University, Reed studied English under the influential but wayward Delmore Schwartz, a benzedrine-gulping depression poet with whose persona the impressionable Reed developed a lifelong infatuation. This relationship with Schwartz was crucial. Not only did the old poet inspire a passion for words in his young charge, but also a magical faith in their power.

When I knew Reed, which was several decades later, he told me that his most notorious song, Heroin, the signature tune of the Velvet Underground, the music-changing band he formed in the 1960s with John Cale, was written long before he tried heroin. The entire song was a feat of literary imagining, à la Delmore Schwartz. This ability to conjure up other worlds, and imagine them in detail, was both the fountainhead of his musical greatness, and a reason to suspect him constantly. As Reed himself said: “I play Lou Reed really well.”

The other great mentor who helped shape the imaginary Lou Reed — the shades, the leather, the bisexuality — was Andy Warhol, who bankrolled the Velvet Underground and designed the famous banana cover of their first record, The Velvet Underground & Nico (1967). Warhol’s switch from a chubby Slovakian shoe illustrator, with no hair, into a silver-wigged giant of pop art, was an act of extraordinary self-creation, which provided Reed with an under-your-nose example of how to transform yourself into an imaginary persona.

Amusingly, Wall collects the comments of the real-life cast of wacky Warhol acolytes who appear so memorably in Walk on the Wild Side — Little Joe, Candy Darling, the Sugar Plum Fairy — and discovers they barely knew Reed. “I met him once at a party,” remembered Holly Woodlawn, who shaved her legs and then he was a she. Reed was envisaging their lives, not describing them.

The break-up of the Velvets was ugly. Reed got rid of Cale, the brilliant Welsh multi-instrumentalist who had made the band unique, and began a scary spiral into rock craziness. Heroin turned out to work exactly as he had imagined it would. The bouts of hepatitis that caused his liver to fail, and eventually killed him, date from the dark years of this “dyed-hair faggot junkie trip”.

At one point, hilariously, he gave up music and went to work for his father as a typist (“I type really well”). But that was never going to work. At home, he found himself a small-town wife, Bettye, remembered chiefly for the black eyes she began to sport. Like all the women in Reed’s life, she is little more than a name. The same goes for the men. In the case of “Rachel”, the bearded transvestite with whom he lived for three of his most chaotic years, we don’t even know what his/her name actually was.

Salvation came in the shape of another besotted Reed fan, David Bowie, who succeeded in getting him to record his most successful solo album, Transformer (1972), the one with Walk on the Wild Side on it. A few years later, Reed thanked Bowie in a London restaurant by launching himself at him across the tables and punching him on the nose.

All this is dramatically different from the Reed I knew, who was a pussycat: one of the sweetest people I ever worked with. I got to know him in the late 1980s when we made a television film of Songs for Drella, the posthumous opera about Warhol he wrote with Cale. In those days Reed was married to his second wife, the Latino designer Sylvia Morales, a powerful force for good in his life for a decade, but who barely rates a mention in this text. The Reed I knew never drank more than a glass of wine with his dinner, and was always moaning about the amount of butter I put on my bread.

Down the line, when that proper biography gets published, it will reveal a sensitive and damaged soul, who hid his shyness behind midnight shades. No such complication makes it into this book. The reason it remains a far better effort than most speed-rushed death tributes is because of the writer’s in-depth knowledge of the Lou Reed back catalogue. What we really have here is an extended discography, with lots of helpful footnotes.