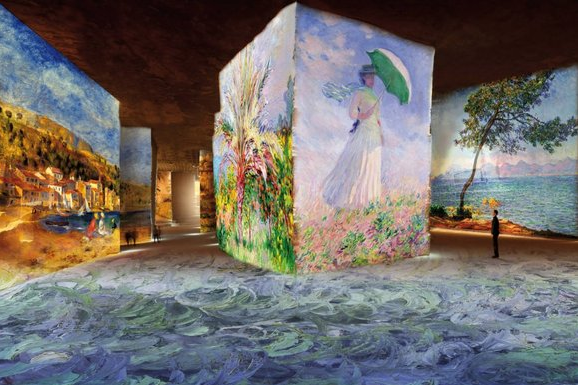

So there I was, deep underground in the south of France, surrounded by 50ft Monets and Renoirs the size of a football field, when the yawning began. More 50ft Monets: more yawns. More mega-Renoirs: still more yawns. I should have been noticing the impact of Mediterranean colour on the important artists enlarged so enormously down here — Matisse and Bonnard, Signac and Chagall, Derain and Dufy — but instead my thoughts began quickly to drift, to the topic that had vexed me for much of the summer: the awful state of the art world.

There’s been lots of grumbling on this matter of late. Various critical Cassandras have flounced in and out of print to announce their dismay at art’s condition. Several important voices have actually chucked in the towel. Chief among these refuseniks was the much admired American art writer Dave Hickey, who announced huffily last year that he wanted out. “What can I tell you?” he growled on the subject of the art world’s decay. “It’s nasty and it’s stupid. I’m an intellectual, and I don’t care if I’m not invited to the party. I quit.” Hickey, who teaches in Las Vegas, had the particular misfortune of having to deal full-on with that especially crass expanse of cultural tomfoolery that is the American art world. Things are bad everywhere, but they are truly tragic in the home of the brave, where the rise of the hedge-fund classes has had such a disfiguring effect on the values of art.

The extraordinary growth and survival of art in the current recession have placed it in a financial category of one. And some very rich cockroaches have been attracted to the fiscal fabulousness. Even our own Charles Saatchi, the man who can fairly be said to have started it all, rushed into print to complain about “the hideousness of the contemporary art world” with its “Eurotrashy, Hedgefundy Hamptonites”, its “trendy Oligarchs and Oiligarchs” and “the art dealers with masturbatory levels of self-regard”. Rarely can a pot have spied this much blackness in the surrounding kettles.

Saatchi is, of course, right. The mercantile thrust of the contemporary art world is ugly and inglorious. Top of my list of events to avoid this autumn is again the Frieze Art Fair, which is to the proper appreciation of art what speed-dating is to the lasting relationship. Where the Cassandras are wrong, however, is in heaping all the blame on the rich and shallow. Yes, the hedge-fund managers and the oiligarchs are a ghastly presence, but art has always attracted money and always managed to survive money’s terrible influence. Far more worrying is the shift in internal values engineered at the heart of the art world by that especially dangerous and unnecessary species: the curator.

Who the hell invented “curators”? For 5,000 years, art got on perfectly well without them. Now, suddenly, they are everywhere. I should immediately add that I am not thinking here of those learned bods at the British Museum or the National Gallery who specialise in particular stretches of the collection and whose wealth of knowledge, acquired over the years, is such a valuable cultural asset. Those curators are among art’s heroes. The ones doing the damage are the berks who run the biennales, who befuddle us with artspeak and “curate” events of ever-increasing unnecessariness, who busily privilege their creativity over that of the artist. Hickey’s complaint that anyone who has “read a Batman comic” would qualify for a career in the art industry holds especially true of the curator. They are the real villains of contemporary art.

I repeat all this here because these are the unwanted thoughts that began tumbling through my mind as I commenced my useless wandering among the giant Monets, the humongous Renoirs and the mega-giant-humongous Chagalls that currently surround you in the Carrières de Lumières (Quarries of Light), in the fiercely touristic Midi village of Les Baux de Provence. The quarries were created in the 19th century by miners ripping up the hillsides to reach the white limestone buried beneath. Van Gogh, who was confined in the nearby asylum of St Rémy, where he painted some of his most hallucinatory imagery, produced several pictures of the Provençal quarries: it’s another, and better, reason to visit them. His paintings notice something so unholy and violent in this frantic clawing at the landscape and the brutal slicing of the rocks.

These days, the quarries have been turned into a huge underground cinema, in which giant imagery is projected onto the quarry walls, accompanied by a soft musical soundtrack of jazz and Debussy. This display consists of seven sections, each of which focuses on a different artist, or group of artists, whose work was influenced by the Mediterranean coast. We begin with Joseph Vernet, an 18th-century sea painter commissioned to record the local ports. Next come the impressionists, the pointillists, the fauves and finally a big blue climax devoted to Marc Chagall.

The event is part of Marseilles’s spell as this year’s European Capital of Culture, and its curators have obviously set out to create an enveloping experience that drenches your horizon with colour and throbs massively all around you. What I was meant to feel, I suppose, was a sense of underground awe: sensations of uplift and colourific amazement. It is not every day, after all, that you find yourself looking up at Matisses the size of small cathedrals. At seemingly infinite expanses of Chagall. Or giant Suzanne Valadons who jump out of Renoir’s marvellous Dance in the City and start waltzing all over your head.

From my own busy clicking, I know all this photographs well. It’s the reason I was down here: I had seen the press pics, and they looked amazing. Indeed, the first glimpse of the extra-large underground impressionism is exciting enough. Yet how rapidly the pleasures fade. After a couple of optical sweeps, you know exactly what to expect next. The three quarters of an hour that remain begin to drag.

The problem here, as in so much contemporary art experience, is the lack of actual content. Something to think about or understand. Once you have gone “wow” a couple of times at the sight of all this virtual enlargement, nothing deeper awaits you. The paintings are already familiar and gain little from being hugely out of focus, while the constant shifting of the imagery allows nothing new to stick. Were they alive today, Monet, Renoir, Matisse and perhaps even Chagall would have recoiled with horror at the crude subterranean blurring of their intentions by these arrogant curators. And the moment you step out of the virtual darkness of the Quarries of Light and back into the genuine Provençal sunshine, the entire experience disappears from your memory faster than a darting lizard.