The good news with the Royal Academy’s beginning-to-now survey of Australian art is that it’s a bright idea for a show, and probably a timely one. The Academy used to attempt these huge national surveys at regular intervals, and, in past exhibitions devoted to the art of Germany, Italy, Russia, gave us some useful big pictures. Yes, we all quibbled about missing artists, misread moments, misleading proportions and the rest, but they remained informative events that enabled us to trace the larger narratives that create a national art and recognise the shared impulses.

All that is true of the academy’s Australia fest, and there is the extra plus that dealing now with Australian art seems on the money as far as the zeitgeist is concerned. There’s a sense in art today that the old powers have faded and the new powers have arrived: that Germany, Italy, Russia have had their say, and it is time for the Nigerias, the Venezualas, the Irans and, yes, the Australias to grab the mike. So that’s the good news: it’s a useful show, and a pertinent one.

The bad news is the art itself, which isn’t impressive enough, often enough, to warrant such a weighty inspection. Every now and then something interesting comes along, but as an overall national achievement, the contents of this display feel lightweight and provincial. Considering how much power there is in the land itself — what a unique and fiery landscape we are dealing with here — the response of Australia’s artists has a tinny tone to it, a lack of muscularity, that feels wrong. Here is a nation, I ended up musing, in which the wrong people became artists. The stockmen should have grabbed the brushes from the chaps who went to Paris, or those who came to London to join the Royal Academy.

The display takes landscape as its central theme and looks back on the 200 years or so since a lucky dip of colonists, missionaries and convicts began their chaotic attempt to depict these thoroughly foreign climes. Their first artistic stumbles actually provide the show with one of its most intriguing stretches. Here was an arkload of different types of artist from Europe, transported to the other side of the world and forced to make visual sense of a landscape unlike any they had seen before.

George French Angas, from Newcastle, paints a fiery sunset in the desert with a trio of emus strolling across the front of it. John Glover, from Leicestershire, gives us a vast panorama of Tasmania with a dotting of kangaroos in the middle distance. These handily placed kangaroos, emus and dingoes have clearly been asked to perform the task that grazing cows generally perform in English landscape art: add some interest to an empty stretch.

The effort to turn Australia into somewhere familiar is even fiercer among the travelling German and Swiss Romantics, who search out mountains that look like the Alps and sunny bays that feel like Naples. Only occasionally do we encounter a landscape so fully different that not even the efficient vision of the German Romantics can make it look convincingly Alpine. I wouldn’t like to be lost at night in the Dandenong Ranges, painted by Eugene von Guerard in 1857. In a valley as primordial as this, there must surely be dinosaurs lurking under the ferns.

The German journeymen and the painting convicts were not, of course, the first artists in Australia. That sad honour goes to the indigenous Aboriginal peoples, who were shunted aside, murdered and betrayed. Their presence in this show continues to feel problematic and tokenistic. Having seen fragments of their ancient art in situ — carved onto rock faces, scratched into lofty overhangs — I know them to be the creators of a mighty artistic tradition that seems actually to be baked into this great land. Aborigine art, in situ, driven by the huge survivalist imperatives that created it, is an art of tremendous power and pertinence. Exactly what the show needs. Exactly what it doesn’t get.

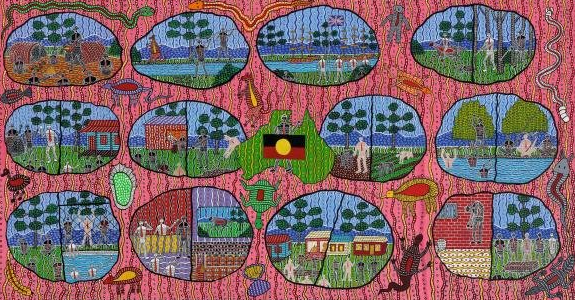

Instead, there are dull canvas approximations, knocked out in reduced dimensions, by a host of repetitive Aborigine artists making a buck. Out of a tremendous indigenous tradition, fired and inspired by an enormous natural landscape, the Australian art world has managed to create what amounts to a market in decorative rugs. Opening the show with a selection of these spotty meanderings, and discussing them in dramatically hallowed terms, cannot disguise the fact that in most cases the great art of the Aborigines has been turned into tourist tat. Only Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri, in a dense and undulating landscape of cosmic dots called Warlugulong, successfully evokes the vast rhythms of the outback.

Another dip in the show showcases the efforts of the so-called Australian impressionists to capture the rhythms and tones of fin de siècle Australia. As the 19th century turned into the 20th, Tom Roberts, Charles Conder, Arthur Streeton and the particularly awful Sydney Long set about creating a “national school of Australian art” by once again re-employing European methods in Australian locations. With much overuse of Courbet’s palette knife, the Dorset-born Roberts manages to make the coast at Mentone look passably like the landscape near Weymouth; while an artist’s camp in the bush becomes a scout camp in the New Forest. A huge triptych by Frederick McCubbin called The Pioneer — a woodcutter, his wife, a baby, their sense of destiny — is as fully sentimental as any of the Victorian poverty porn that so obviously inspired it.

It’s not until we reach the 1930s and 1940s that a group of painters finally emerges whose work seems fully Australian. Among the light-bleached portrayals of the Australian landscape, the most convincing are by Albert Namatjira, an Aboriginal artist trained in European techniques, whose glowing watercolours capture perfectly the shifting light of the desert. Full of insider knowledge, they are the most sensitive works in the entire show.

Sidney Nolan was not a sensitive artist — strewth, cobber, but he wasn’t sensitive! — yet his powerful mix of folk-art directness and from-the-tube Australian colour give this parade its most emblematic pictures. Nolan’s famous portrayal of the story of Ned Kelly is a Rake’s Progress set in the bush. Riding into the outback on a wobbly brown horse, a bent rifle for a lance, a homemade suit of armour on his back, Kelly is the fearless Arthurian hero, Australian style.

While the first European artists to arrive on these faraway shores excitedly explored lots of different types of landscape — mountains, rainforests, coastal bays, valleys filled with ferns — more recent stretches of Australian art have been dominated by visions of the outback. It’s as if the rest of the country has ceased to matter and only the sun-baked emptiness of the bush constitutes a proper Australia.

Fred Williams, a particularly mannered member of the less-is-more school, splatters the delicate emptiness of the desert with thick cowpats of minimalism. As the show grows ever browner and yellower, John Olsen’s Sydney Sun, a giant panel of art installed above your head, successfully evokes the sensation of standing under a cascade of diarrhoea. I think he was actually trying to record the harsh tangibility of the Australian sun.

The crassness that characterises these repetitive responses to the Australian landscape is also in evidence, alas, in the figure paintings of the times. I take the point that Albert Tucker was seeking to portray the sunbathers on an Australian beach in 1944 as lumps of sun-baked meat — no arms, no legs, no heads — for existential wartime reasons, but, jeez, what an ugly painting. And for a complete absence of grace or sensitivity, you would be hard pushed to find an image that could overtake Arthur Boyd’s horrible black studio scene in which a flaying figure with a paintbrush jack-knifes across the canvas like a man being thrown out of a bar.

It’s not until the show enters its final stretches, and we reach the contemporary world, that Australian art becomes properly varied again, and a whole new range of moods and tonalities pop up. In a set of exquisitely crafted sardine-tin sculptures by Fiona Hall, the tin has been cut and twisted into delicate examples of Australian flora on the outside, and energetic episodes of Australian porn on the inside. In a pictorial reprise of Mad Max’s post-apocalyptic feral world, Danie Mellor gives us an ancient Greek necropolis overrun by koalas, kangaroos and Aboriginals. The imported European civilisation is in black and white. The rightful inhabitants of Australia are in colour.