Had you asked me in 2012 which of Britain’s great art institutions would kick off 2013 with the loudest bit of hype, I would have predicted the Royal Academy. It’s that sort of place, and its current supremo, Charles Saumarez Smith, has previous as a hype-meister. It was Smith who was director of the National Gallery during that toe-clenchingly base era when its most famous paintings were repackaged for us in the style of Hello! magazine.

Yet it isn’t the Royal Academy that has opened art’s annual innings with the noisiest claims. Smith’s former employer, the National Gallery, has beaten it to the punch with the announcement that a new Titian portrait has been discovered in its basement, and that the subject of this new Titian is Girolamo Fracastoro, the Renaissance polymath who identified and named syphilis! “Priceless Titian Painting of Syphilis Doctor Rediscovered in National Gallery Basement” trumpeted the resulting headline in the International Business Times.

The news was broken in an article in the Burlington Magazine, the celebrated art-historical journal that has long had close contacts with the National Gallery. Neil MacGregor, the National’s greatest director of recent years, is a former editor of the Burlington. And the current director, Nicholas Penny, is quoted at the top of the magazine’s website, insisting: “Art historians will still be reading and consulting this month’s Burlington Magazine fifty and even a hundred years from now.” It’s a confident shout, and pertinent because this month’s Burlington is the issue that carries the Titian attribution.

The Burlington article is thoughtful and detailed, but it is also highly speculative. Most of its conclusions about the artist’s technique are undermined by the picture’s poor condition. And the identification of the sitter is just as hopeful. Fracastoro was an astronomer as well as a doctor. He studied with Copernicus. But these days he is remembered best for his epic poem of 1530, Syphilis, or the French Disease, in which he gave the great pox its name.

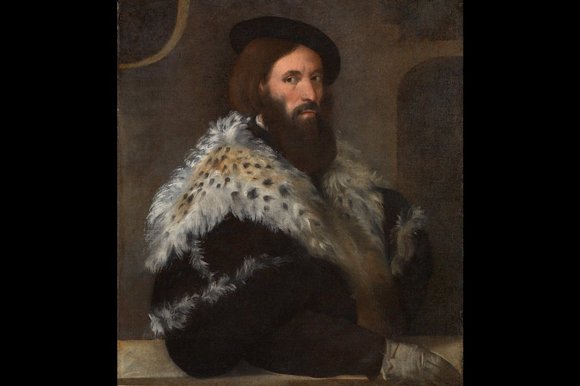

Apparently, the rediscovered portrait bears a 19th-century label on the back naming Fracastoro. The man in the picture, however, looks noticeably younger than Fracastoro would have been in 1530. And, though the only contemporary description of him tells us that “his face was round and his nose snub”, the man in the putative Titian has a long, thin face and an angular, bony nose.

So there’s certainly room for doubt. Yet see how thoroughly the news has already circulated that the new Titian shows Fracastoro! Look him up on Wikipedia and there is the Burlington portrait, freshly pasted in, with the news that “a recently authenticated portrait in the National Gallery has been determined to be that of Fracastoro, painted by the renowned Italian painter Titian”. Blimey, that was quick. Even the BBC’s Your Paintings website now has it down as a Titian.

So enticing is the possibility that the newly identified portrait portrays the doctor who named syphilis that even the generally level-headed Jonathan Jones, in The Guardian, was moved to imagine a scenario in which the notoriously fun-loving Titian consults Fracastoro about his syphilis, then pays the doctor for his treatment with this portrait. “Now at last,” Jones continues at the ecstatic climax of his wanderings among the National Gallery’s Titians, in the company of Penny, “the scientific hero Girolamo Fracastoro, liberated from the neglect that saw his portrait sentenced to oblivion, takes his place among the gods and goddesses, patricians and prostitutes painted by one of the most beguiling magicians ever to wield a brush in what I, for one, believe is the greatest collection on earth of Titian’s paintings”.

All this gush would be forgivable if the painting in question were as impressive in the flesh as the claims made for it are on paper. But it isn’t. Rescued from its dark banishment in the basement, it now hangs in Room 10 of the National Gallery, surrounded by other Titians and further fine examples of Venetian painting, looking distinctly underwhelming and overpromoted. If this is a Titian, then it is not a very good one.

The first problem is the sitter’s presence, which seems small and standard when compared with the other Titian sitters in the National’s collection. There is none of the psychological force that glues you to the thoughts of the marvellous Man with a Glove on the opposite wall; and none of that fabulously brave picture-making that thrusts an elbow in your face in the nearby Man with a Quilted Sleeve.

The Burlington article admits the painting is in poor condition, which may explain a lot. Much is made of the skill shown by the artist in capturing the textures of the big fur coat, made of lynx, that the putative Fracastoro is wearing. It’s definitely the best bit of the picture. But in the next gallery, in Titian’s superb group portrait of the Vendramin family, the leading Vendramin also sports a coat lined with lynx, and in that instance the painting of the fur is beyond good — it is actually breathtaking. So swift and subtle and nuanced.

The single most un-Titiany thing about the new Titian is its background. The putative Fracastoro seems to be standing in front of a grey wall in which we see two peculiar openings: a circular one above his right shoulder and a kind of rectangular doorway above his left. This weird architectural arrangement appears nowhere else in Titian. The Burlington admits that it cannot be explained by recent overpainting. So why would Titian add such a strange background to what is otherwise an unambitious image?

Before it was hauled out of the basement, the painting was attributed to Francesco Tobido, known as Il Moro, who studied under Giorgione in Venice and worked in Fracastoro’s home town, Verona. Though he is largely forgotten today, we know that he, too, painted the syphilis doctor. Indeed, the only time I have seen a background like this before was in Il Moro’s portrait of a couple — one of whom is wearing thick fur — that hangs in the Doris Ulmann Galleries at Berea College, Kentucky.

The other much-hyped portrait of the year so far is the first painted likeness of the Duchess of Cambridge, by Paul Emsley, unveiled last week by the National Portrait Gallery. Some of you must have seen me disliking it on the BBC news, because you have kindly written in to point out that I, too, am no oil painting. No arguments there.

Yet I realise it was wrong of me to describe it as “disappointing”. I apologise unreservedly. It is substantially worse than that. It’s not just that the composition has been crudely borrowed from a passport photograph, or that the lack of proper texture gives Kate the complexion of an embalmed corpse. The very worst thing about the picture is that Emsley has managed to make Kate Middleton look like Edwina Currie.