I have lost sight of what is and what is not part of the Cultural Olympiad. So many surprisingly good exhibitions with a British slant have opened this year that it is difficult to tell if they belong in the Olympic lane or not. Britain may be a world-class nation when it comes to synchronised jingoism (lurking group jingoism that sits just beneath the surface), but it’s not a leading nation when it comes to shot-put jingoism (big, heavy jingoism that lands at your feet with a thud). That kind of display we leave to the French, the Chinese and the Hungarians.

The discreet nature of British jingoism has proved to be a surprising force for good in the difficult sport of exhibition-making. Not one of the official Olympic shows so far has suffered from flag-waving obviousness or a lack of complication. All have delivered more than might have been expected. That is particularly true of the revelatory British Museum display that is Shakespeare: Staging the World.

The event does not begin discreetly. The first words you see here, on the opening wall, describe Shakespeare as “Britain’s greatest cultural contribution to the world”. It’s a big claim that few would dispute. But his enormous international reach is a testament to the power of his words. About the man himself, we know absurdly little. His work may be a bottomless pit, but his human presence is one-dimensional. Who, therefore, would have expected the current display to feel as relentlessly revelatory as it does?

The show begins by evoking Shakespeare’s London. One of the first objects we encounter is a bear’s skull, dug out of the mud at Southwark. It belongs to one of the ursine unfortunates set upon by dogs for the entertainment of the London crowd. The poor bear has had its teeth ground down so that its torture might last longer. Next to the skull is a rare surviving poster announcing the pleasures of bear-baiting. No similar poster has survived advertising the pleasures of Shakespeare.

Southwark was the capital’s entertainment quarter. It was where the brothels were, the drinking dens, the gambling houses and the theatres. These days, we watch Shakespeare in state-of-the-art architectural masterpieces with perfect acoustics, but his first audiences carried about two-ended forks: one end for removing ear wax, the other for picking your teeth. To get to Southwark, you had to be rowed across the Thames by one of the gangster boatmen who plied their trade on the river. The reason we know so much about the textures and habits of the Southwark visitors is because so much stuff fell out of their drunken pockets, to be washed up, centuries later, on the Thames foreshore and to end up, eventually, in the British Museum.

Shakespeare’s London was strikingly cosmopolitan. Not only was all the world a stage, a good many of its actors were over here, taking our jobs. As long ago as 1517, St Paul’s churchyard was the location for a riot in which rampaging crowds set fire to streetfuls of small businesses while demanding an end to immigration. Shakespeare would certainly have known the Moroccan ambassador, who appears here in an anonymous portrait from 1600, exotically costumed in robes and turban. This same ambassador, says the show, would have played a role in the imagining of Othello.

The organisers have clearly set out to draw constant parallels between Shakespeare’s Britain and our own. The visceral impact of the objects that convey this message is something no literature, however fine, can match. Having successfully brought Shakespeare’s London to life, the display goes on to tackle an assortment of the imaginative worlds his work inhabits, and here, too, it succeeds in plucking them out of the distance, Venice, where Othello pined for Desdemona and where Shylock made his fateful bargain with Antonio, is the subject of what we might call a Shakespearian exhibition device: a show within a show. A series of pertinent Jewish texts, a set of scales, a heap of ducats conjure up the potent Jewish presence in the city of sails and sales.

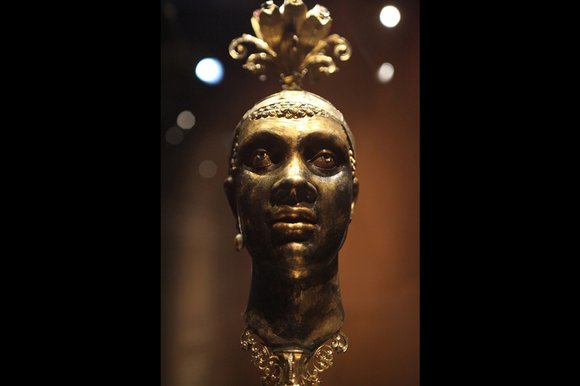

Nearby, an assortment of exotic Venetian sculptures and some blingy German drinking vessels featuring staring black faces make equally evident the otherness with which every European Othello has always been freighted. Throughout the show, a succession of notable British actors attached to the RSC pop up on video to present key matching moments of Shakespearian text. My, how well they work. Antony Sher’s 30 seconds of Shylock asking if he would not bleed if we pricked him are an astonishingly effective morsel of drama; so is the mature questioning of Harriet Walter’s Cleopatra, raising her voice in forlorn hope to beckon Mark Antony for one final lusting. You get not only Brutus’s famous agonising over the assassination of Caesar, but the actual gold coin he minted to commemorate the event.

All this makes Shakespeare’s imaginings tangible, and has the effect, also, of blowing away some of the divine fog that surrounds his own presence. When I say the show marches Shakespeare down from Olympus, I mean it as a compliment. He grows here into a recognisable inhabitant of a recognisable world, a figure of substance.

The insights that are provided into the genesis of his plays also struck me with the force of a revelation. Thus, the most plangent stretch of a plangent show is the section dealing with Macbeth. Against the backcloth of James I’s accession to the English throne — the coming of a Scottish king — the display picks its way compellingly through the real-life dramas that accompanied James’s arrival. Macbeth’s witches are traced back to their origins in the real witches of whom the king was notoriously scared, and about whom he wrote a curious pamphlet. A grotesque metal collar and mouth guard, in which Stuart witches were chained up, brings home the terror with which they were regarded; while a collection of eerie Scottish amulets, preserved from the clans, pinpoints the devilish contribution of Scottish thinking to the newly united kingdom.

Another superbly informative section deals with exploration and travel at the time, and their impact on King Lear and The Tempest. Caliban was almost a credible creation of nature when compared with some of the horrible island monsters imagined or half-witnessed by the voyagers who returned from faraway places in Shakespeare’s time. Over there is yanked to over here. And Shakespeare descends a few score yards from the summit to which his adorers have banished him, and stands before us less withered by age, his variety less stale. If not pricked, cut and bleeding, then certainly poked about and examined. Not yet a mortal — not even the British Museum could achieve that — but, rather excitingly, a man of his times.