Best loved. Enduring. Magical. Inventive. Unsettling. Finding adjectives to describe Alice in Wonderland is a piece of cake. If you threw a dart at a dictionary, the chances are it would spike something appropriate. In his introduction to the paperback edition of Lewis Carroll’s nursery classic, on sale in Tate Liverpool’s bookshop, the elongated novelist Will Self chooses “curious” as the adjective that best encapsulates the book. Having careered through the dissymmetric Tate display devoted to Alice’s discombobulating influence on art, blundering from one discrepant artwork to another, my own Alice word would be: useful. Just as a lot of adjectives fit Alice, so too do a lot of artistic impulses.

Building a show around Alice in Wonderland is a cunning bit of exhibition-making. Not only can the curators involve whatever they fancy in their event, because nothing is truly out of place in an Alice display, the gallery has found a way to pleasure all age groups simultaneously for Christmas. Nominally a children’s story, Alice’s underground odyssey began to trespass on adult territory as soon as it was published. As the LSD-munching 1960s artist Adrian Piper, whose contribution to this Alice fest consists of a set of migraine-inducing psychedelic throbbings, of the sort you used to find on Grateful Dead albums, puts it in her wall text: “Purports to be for children, but don’t be fooled.”

Since its first appearance in 1865, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland has never been out of print. The book has been translated into 98 languages and numbers more than a century of editions. The best foreign translation is said to be Nabokov’s. Kafka was changed by it. And Borges. Thus, a book that appears to us to be woven inextricably into the British childhood turns out to have a veritable United Nations of nationalities. From René Magritte to Walt Disney, from Salvador Dali to Max, an impressively international cast of artistic figures is presented here as victims of its influence.

Where, then, can an exhibition investigating Alice’s impact begin? At the end, is Tate Liverpool’s slippery answer. The first thing you encounter is an installation of the show’s newest artists. Luc Tuymans, the fashionable Belgian anaemic (nobody paints pictures as waxen as Tuymans’s), presents a typically pale landscape that in another context I would happily have understood as a snow scene set in Antarctica. Here, the ice formations and snow caves evoked by Tuymans are described as Wonderland. Going all the way round the gallery, meanwhile, is a thin black line, stuck there by the American conceptualist Mel Bochner. It turns out that the line encircles the room at exactly 9ft, the size Alice grew to when she ate the cake with Eat Me written on it.

Beyond proving that Alice’s adventures are an outrageously flexible prompt, nothing too tangible is achieved in these opening exchanges. Upstairs, however, the exhibition pops up again with a new beginning: an engrossing historical display that plunges us into the textures and time scales of Alice’s creation. Victorian photographs. Victorian display cases. Victorian paintings. Victorian moods. Reversing forwards through 150 years, the Tate show suddenly tackles the shadiest of Alice’s many realities: the first one. A twilit display bustles through the well-known tale of how the book came to be written: how the Rev Charles Lutwidge Dodgson took Alice Liddell and her two sisters on a boat trip up the Isis, in Oxford, and how he made up a story as they rowed about a little girl called Alice who followed a talking rabbit down a rabbit hole. Alice liked the story so much, she begged Dodgson to write it down. Which he did, adopting the pen name Lewis Carroll and attempting, initially, to illustrate the book himself.

Dodgson’s scratchy, spiky, weird Alice drawings, collected here in a rare showing, struck me as remarkably contemporary in mood and look. I doubt that Tracey Emin’s illustrations to Alice would be markedly different. Yet his own era was not ready to understand these nervy scratchings. John Tenniel was brought in to illustrate the book and give it its defining form. His celebrated drawings, which Dodgson apparently disliked, and which have been hidden here at the bottom of a display case, as if to allow the many surrounding Alices to express themselves, have a sinister quality to them, a sense of lurking psychology. More forcefully even than the text itself, they suggested to the Victorian imagination that this might be a tale with adult resonances.

To its credit, the exhibition avoids joining in with all that nasty recent speculation about Dodgson’s paedophile interest in Alice Liddell. None of his more suggestive photographs of her is included, and the focus is maintained on his endearingly wonky attempts to record her sweetness. The inclusion of method-acting children in off-the-shoulder tunics, photographed by Julia Margaret Cameron, makes it simultaneously clear that photography, in these shadowy early days, was desperate to mimic the range of painting.

Dodgson’s photographs of his artistic friends, the pre-Raphaelites, are decent rather than brilliant, but they give the show an excuse to display Holman Hunt’s preposterous Triumph of the Innocents, which I welcome for entirely childish reasons. This spectacularly silly picture shows the souls of the babies murdered by Herod accompanying Mary and Jesus on their flight into Egypt, dressed in what appear to be space helmets.

Also included is Arthur Hughes’s embarrassingly bad Lady with the Lilacs, supposedly Dodgson’s favourite painting, an anatomically disastrous portrayal of a girl in a garden, in which desire to protect an innocent, and desire pure and simple, have mixed themselves into a quintessentially Victorian form that certainly cannot be discounted in any consideration of the impact of Alice in Wonderland.

One of the best things about having Alice’s adventures as the inspiration for a show is the freedom it gives you to skip from chapter to chapter without needing to explain the leaps in your narrative. Having made a reasonable attempt to understand Alice’s origins, the display lurches next onto the entirely different terrain of Alice’s influence on the surrealists. Which was colossal. Surrealism thrived on making unexpected connections, and the view that all surface realities hide hidden, deeper ones is a surrealist truism. Dorothea Tanning’s spooky Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, painted in 1943, in which two doll-like little girls are confronted by a giant sunflower in a hotel corridor, must have been influenced by the corridor with many doors in which Alice finds herself in her first moments in Wonderland; while the huge disruptions of scale that Alice soon experienced, growing tiny and then huge, were just as clearly an influence on the giant apples that Magritte jammed into his small rooms.

My own evidence for the huge impact of Alice on the surrealists is the complaint about Alice’s appearance voiced by Humpty Dumpty in Through the Looking-Glass: “Your face is the same as everybody has — two eyes… nose in the middle, mouth under… Now if you had the two eyes on the same side of the nose, for instance — or the mouth at the top — that would be some help.” Yup, Carroll invented Picasso.

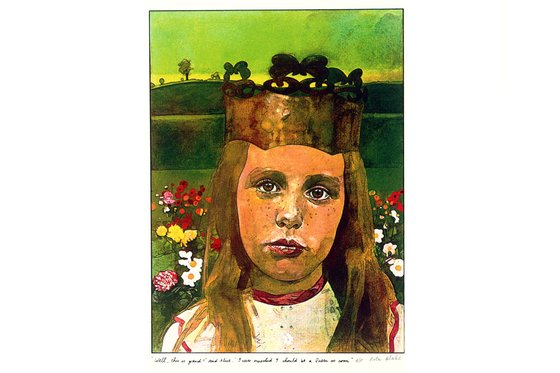

Until now, the exhibition has had a passable sense of purpose to it. In its next phase, though, Alice’s journey through post-war and contemporary art, things grow chaotic. Piper’s psychedelic doodlings make it fully obvious that, by the 1960s, Alice had become the patron saint of anything goes. I particularly enjoyed the Alice happening that Yayoi Kusama organised in Central Park in 1968, for which everyone stripped off and covered themselves in polka dots. Peter Blake’s illustrations for Through the Looking-Glass, on the other hand, which I have previously underestimated, return to Tenniel territory and present Alice’s journey as an anxious awakening.

In the 1990s, various women artists, mostly American, used the basic prototype of a little girl wandering about in a dark world as the excuse to present Exorcist-style self-portraiture. While the steamy blow-by-blow description of the action in a porn film called Arsewoman in Wonderland, transcribed for us by Fiona Banner, reminds us of the pre-Freudian meanings that were there from the beginning in this eerie tale of a little girl disappearing down a dark hole. So it’s a show that pulls us in many directions. But there is a final consensus. Because, once Alice’s adventures had revealed to us the rabbit warren of other realities that lay beneath the everyday, who among us could ever again believe the far-fetched, fantastical notion that everyday reality is all there is?