Being able to describe the German painter Gerhard Richter as “the German painter Gerhard Richter” is a pleasant surprise. Until Tate Modern unveiled its engrossing Richter retrospective, I was unsure of what he actually was. He may be one of the most adored artists currently at work in the world, but most of us would previously have had difficulty knowing which box to put him in. He takes photographs. He presents installations. He makes sculptures with glass. He’s figurative. He’s abstract. He even designs stained-glass windows.

But now we know that, underlying all this furious conceptual skipping about, Richter is, at heart, a painter. And an old-fashioned one at that.

The clear identification achieved by this event is important because Richter is important. Most experienced art observers would have him in their top three of living artists. Indeed, now that Richard Hamilton and Lucian Freud have simultaneously departed in this awful summer of art deaths, many would place him at number one. That is the heft of the career we are surveying here. This is a show with a sense of anointment about it.

Certainly, it is hard to imagine a set of weightier origins than Richter’s. He was born in Dresden in 1932, the year before Hitler became chancellor. As a teenager, he watched the Nazis go to war, watched the bombing of Dresden, watched his own family involve itself directly in the madness. One of the spookiest of his early paintings is called, disingenuously, Uncle Rudi. It shows a Nazi soldier in full grey uniform smiling at us sweetly. That is Richter’s Uncle Rudi, on his way to the Russian front, where he was killed a few weeks later. Richter painted it from a snapshot 20 years after the event.

The relationship of his art to his country’s dark and momentous history is perhaps the most powerful force that shapes this retrospective. The most poignant of his early pictures shows little Gerhard himself, as a baby, in the arms of his pretty Aunt Marianne. She is blonde and happy. He is struggling and puzzled. Aunt Marianne had a history of mental problems. In 1945, she was executed by the Nazis as part of their eugenics programme. Thus, the past has clamped its teeth into Richter’s art like an angry bull terrier. Or is that a giant schnauzer?

As if growing up in Nazi Germany were not enough, the next dubious favour history granted him was to dump him in the middle of the cold war by turning his bombed-out homeland into a communist state. East Germany was an astonishingly bleak place to live. I had the misfortune to pass through it on numerous occasions on my way to my own betrayed homeland, Poland, and will never forget the smell and ugliness of the DDR. Or its colour scheme. It was the greyest place I ever saw. Everything — the towns, the trains, the people — was the colour of concrete dust.

Richter would later produce a large body of monochrome grey paintings. Perversely, they form one of the most beautiful stretches of this show. In this superbly subtle room, every grey feels varied: different tone, different texture, different aura. A connoisseur of greys, you feel, is displaying his expertise. Yet the refusal of Richter’s greys to feel bleak or dull or unsanctified tells us something important, too, about the transformative power of art. Richter’s output is shaped by history, yes, but not by the one-size-fits-all history you find in textbooks. Shaping this show are intricate ex-Nazi, ex-East German understandings that are peculiar to him.

All this needs considering because Richter’s origins have such a powerful impact on the art ahead. One of the reasons his career feels so weighty is because of the momentous history it spans. Another is the size of the historical questions his work seems to pose. Whose history is true, the conqueror’s or the vanquished’s? What is the difference between history as it is lived and history as it is remembered? What sort of society have I come from?

And how has that society been presented to me? Richter’s pictures never ask the questions as bluntly as that — they are far more subtle and strategic and sneaky — but these are the sorts of monster questions that appear to linger, unseen, beneath the deceptively tranquil surfaces of his output. The Loch Ness questions.

The display actually begins in 1961, the year he decamped to the West. He was already 29, so the psychological baggage he brought with him from Dresden was surely indestructible. I would have liked to see examples here of the art he made in East Germany before his escape. As an official state mural painter, Richter was a privileged insider. He worked on the murals at the Deutsches Hygiene-Museum, on assorted East German kinder gartens and even on the headquarters of the Socialist Unity party in Dresden. Yet this show embarks on a bit of Deutsches hygiene of its own by ignoring this early life entirely. By the time we catch up with him, Richter has shed all obvious traces of his former identity and become a sort of German pop artist — a painter of Ferraris and holiday brochures, sex scenes and kitchen equipment. A butterfly has left its chrysalis. It’s an illusion, of course. It takes more than a move to the West to get the smell of East Germany out of your pores. The most insistent attitude Richter brought with him from the East was doubt, a refusal ever to believe what he saw. His grim 1960s pop art is far too pessimistic and smart ever to pass for a celebration of consumerism. A speeding Ferrari he painted in 1964 is such a troubling and sinister presence. Battleship grey in colour, driven by an anonymous Stig hiding behind dark windows, this is a Ferrari with the vehicular ambitions of an armoured car or a guided missile.

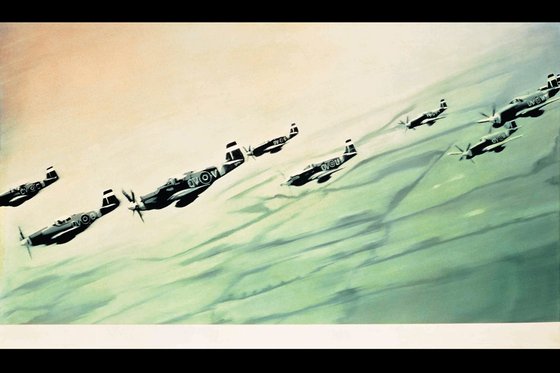

The sinister grey Ferrari was painted from a picture in a lifestyle magazine. Richter has left a telltale band of text at the painting’s edge to make this clear. He does the same with his paintings of porn stars, and with his neat clusters of American bombers passing over Dresden. This is not actual history that is being probed and examined here, but the ways in which that history was repackaged and disseminated by the consumer society Richter encountered in the West. This entire retrospective amounts to an exhibition-long investigation of the difference between what is presented to you and what is actually there.

Before you even enter the show, in the foyer, the Tate’s designers propose another mind-messing Richter conundrum: is he figurative or is he abstract? One huge agenda-setting work depicts 48 of the world’s greatest artists, scientists and thinkers, from Einstein to Wilde, gathered together like the portraits in a school yearbook. On the other side of the entrance, another huge agenda-setting painting features a close-up of a single yellow brushstroke that continues along half the length of the Turbine Hall, until it reaches the sort of distance that Usain Bolt runs. Which is more important — 48 of the biggest contributors to civilisation? Or a single brushstroke? By the time you reach the other end of the show, you have learnt the answer is: neither. Both are painterly illusions.

The display is arranged in sections that are simultaneously self-contained and chronological. Richter’s main concerns are tidied up into helpful clusters, but the overall shape of his career also emerges. And the battle between image and paintwork, reality and illusion, shapes the entire journey. Thus, the Ferrari picture in the cynical pop section at the beginning acquires its questioning mood because it is copied from a magazine, and because Richter, in what is to become a trademark gesture, combs a dry brush over the painted likeness to disrupt its outlines, blur its focus and give the image a sense of added movement, like the lines you get on a cartoon. Later on, a cluster of cityscapes feel as energetically abstract, close up, as a good Pollock, but when you draw back from them, they gradually reveal their other identity as tragic views of Dresden after the bombing.

The organisers have made a conspicuous effort to mix figurative Richter with abstract Richter, and to present both as different sides of the same coin. As the show progresses, though, abstract Richter seems to take over. If there are disguised political concerns hidden somewhere within the giant squeegee symphonies and Shrek-sized brushstrokes that begin to dominate the show, they are well hidden. My feeling was that his art was increasingly reaching beyond the grim German history he was born into and trying to connect with a bigger, older German past: with Wagnerian issues of landscape and the sublime, spirituality and destiny. In the end, paint’s old-fashioned ability to evoke and move is being explored here.

This is such a beautifully shaped retrospective. Where most careers move forward in spurts and leaps, Richter’s feels like one of those Michelangelo sculptures that start out as a rough block and end up as a finished image. Everything was there from the start. It just needed revealing.