Frida Kahlo’s favourite lipstick was a shade called Everything’s Rosy, produced by Revlon. She also used Revlon nail varnish, especially Raven Red, which is basically the colour of dried human blood. For skin care, she chose Pond’s Dry Skin Cream, “preferred by beautiful women in all parts of the world”. And that famous batwing monobrow of hers was enhanced and shaped with a Revlon eyebrow pencil in a bat-black shade called Ebony.

I share this with you to give you an immediate blast of the remarkable sense of intimacy that glues you to Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up, at the V&A. I am not sure I have ever felt quite as spookily close to an important artist. In the bigger world, Kahlo is a feminist icon, the queen of Mexican art, patron saint of identity hunters everywhere, but at this event she’s the woman under your nose, as close as any lover you’ve ever had.

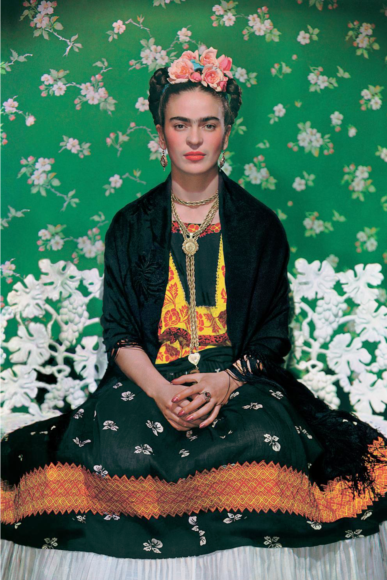

The lipstick and the eyebrow pencil are pointers, too, to an elephant-sized paradox that haunts this event. If ever an artist was adored for being “true to herself”, it is Kahlo: the monobrow, the moustache, the insistently Mexican clothing. Yet, in her case, being “true to herself” actually involved the creation of an elaborate fictitious persona. With Raven Red and Everything’s Rosy, she turned herself into the fantasy Frida we adore today.

It’s a story told in detail by an undies drawer of a show whose contents have literally been snatched from her bedroom. All her life (1907-54), she lived in La Casa Azul, the famous Blue House, in Coyoacan, on the edge of Mexico City, which is now the Frida Kahlo Museum. It’s where she grew up. It’s where she remained with her equally notorious husband, the great Mexican muralist Diego Rivera. It’s where she had her unlikely affair with Trotsky.

But La Casa Azul had another secret. Locked away in the bathroom after her death was a cupboard no one was allowed to enter. For 50 years, the contents of this cupboard — sealed by Rivera — remained a mystery. Not until 2004 did the curators of the Frida Kahlo Museum pluck up the courage to open it. Inside they found a treasure trove of her personal effects — her clothes, her jewellery, her cosmetics, her medical equipment, the corsets she wore after her accident, her letters, the photographs she kept from her youth: the true Frida Kahlo, neatly folded up and preserved.

The V&A has now put a generous selection of these intimate contents on show, amplifying them with films of her in action, more photographs, her jewellery, her costumes and a small but gripping array of her fiery self-portraits: the ones that track you down on the other side of the room and shoot laser-guided stares at you.

She was born Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderon. The simplification into Frida Kahlo was an early bit of topiary. Her father, Guillermo Kahlo, was German and her mother a mestiza — half Mexican, half Spanish — so the Fates toyed with her identity from the off, and the doubts were in-built. In other ways, however, the Fates were kinder, because they made her father a photographer in Mexico City who specialised in architectural studies, but who also took an unusual number of superb early portraits of his beloved Frida.

Not many 20th-century creatives can boast the smouldering, intense, varied record of their young selves that Frida Kahlo could. Guillermo was a good enough photographer to recognise that his unusual daughter, with her spectacular monobrow and her moustache, her perfect neck, her huge eyes, had something about her that the camera loved. So he kept pointing it at her. Posing, presenting herself to a public eye, was part of Kahlo’s inheritance. It’s what she always did and was particularly skilled at.

When she was six, the Fates got nasty again and struck her down with polio, leaving her with a withered leg. When she was 18, the tram she was taking home from college was hit by a bus, breaking a handful of her important bones. The resulting pain tormented her for the rest of her life. Also in the cupboard were the corsets she wore to keep herself upright. They look like something the Inquisition might whip out for a troublesome heretic. To dampen this sinister presence, she painted wild designs on them or, sometimes, in typical outbursts of Mexican outrageousness, a hammer and sickle.

Like everything else here, the corsets have the atmosphere of a relic: sacred mementos you want to touch. The sense of religious intimacy reaches a climax in the prosthetic leg she had made after her own was amputated, shortly before her death. In a final burst of artistic optimism, she ordered up a pair of bright red Mexican booties, with one for the false peg, then attached silver bells to them, so everyone could hear her coming. If you’ve ever wondered why medieval churches were full of saints’ teeth and martyrs’ hair, come to the V&A and shiver in the edgy presence of Frida Kahlo.

What makes this a clever show, as well as a riveting one, is the connections made continuously between her possessions and her paintings. It culminates in a spectacular room full of her dresses, ringed by a gallery of self-portraits and drawings in which she wears the same items, and stares at us with that black-eyed intensity of hers. Andre Breton described her art as “a ribbon about a bomb”. That hits it on the head.

The dresses have an interesting story to tell. The familiar image of Kahlo in full-on Mexican costume, monobrow proudly bristling, has left the impression that she was especially keen to foreground her Mexican origins. What we learn here, though, is that the Tehuana costume she began to sport circa 1929 was a creative confection. She never actually went to Tehuana. Far from being traditional costume, what she wore was a wild assortment of far-flung bits.

So the cosplay was about something deeper than nation signalling. It was, we learn, the upper-casing of the power of clothes to transform and signify: a crazy, artistic search for beauty; a sartorial war against time and tragedy. And what marvellous courage she showed in her hopeless rage against the dying of the light. If modern exhibitions let you touch things, I’d be kissing her prosthetic leg and smearing her lipstick onto my mouth in the mad hope that some of that indomitable spirit might rub off on me. Sube a tu caballo, gringo, and hurry to this fabulous show.

At Sprüth Magers, Cindy Sherman, who we might fairly call an heir to Kahlo’s legacy, also has a new exhibition, and it, too, is spectacularly good. What’s more, it, too, rages against the dying of the light, and does so in a manner that tugs at your heart.

It consists of what appear to be a set of promotion stills from the golden days of Hollywood — the 1930s and 1940s — except this chorus of glamorous leading ladies are at what we might politely describe as a certain age.

They are all, of course, Sherman herself, dressed up to the nines as Carole Lombard or Jane Russell, not in their younger forms, but at the far end of their careers, fading and hollow. The glamour, the pouting, the actorly emoting — pinpointed with astonishing accuracy by Sherman — is but a sad masquerade. You can put on all the haute couture you want, but time will eat your beauty, as it eats everything else.

Frida Kahlo, V&A, London SW7, until Nov 4; Cindy Sherman, Sprüth Magers, London W1, until Sept 1