If you examine the edges of a painting by Lucas Cranach, the chances are you will see a tiny dragon buzzing around them. It’s not actually a dragon. It’s a winged snake. And if you peer really closely, you will find it is carrying a ruby ring in its teeth. “How strange,” you may think to yourself. I did.

It’s what they call a kleinod, a personal emblem, given by a monarch to thank its recipient for good service. Cranach (1472-1553) was given the winged snake as his kleinod by the Elector of Saxony in 1508 and in his subsequent art it took the place of a signature. Flying snakes behind every rock.

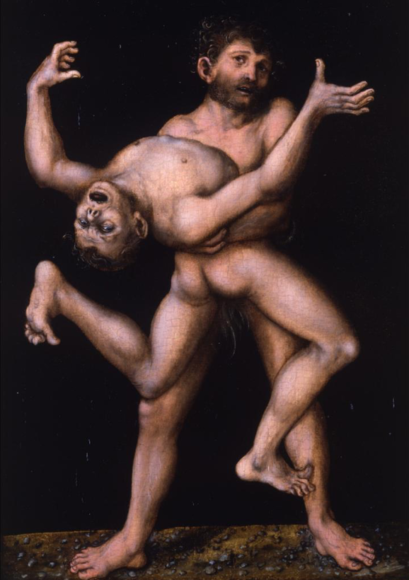

I mention it here to signal his unusualness. With Cranach, everything is slightly off-kilter. His figures are always weird. His mythologies are always peculiar. Even his portraits, the most anchored realm of his busy output, have a cartoonish flatness to them that pushes them closer to the world of symbols. The result is a Renaissance art that has one foot planted firmly in the Middle Ages: the hobgoblins have grabbed it and won’t let go.

It makes every Cranach show a must-go destination. However, the one at the stately home Compton Verney has the added attraction of being surrounded by a beautiful expanse of bucolic garden landscaped precisely with lakes, woods, meadows and buttercups by the great Capability Brown. Cranach v the perfect British summer is an unexpected skirmish.

The show has gathered its exhibits from British collections. Compton Verney owns four pictures by him. The National Gallery has also been generous. So has the Royal Collection. But you would expect that. What I did not expect was for the museum in Truro to have one. Or the Brighton Pavilion.

However, there are not enough of these surprising Cranachs in Britain to create a proper retrospective. Instead, we get a 100m race that speeds through his achievements and then gives itself a lengthy lap of honour with a part two that investigates his continuing influence on contemporary art. In truth, it doesn’t really hold together. But who cares? In my book, a single Cranach is worth a journey, so a dozen of them constitutes an entry in the bucket list.

Cranach: Artist and Innovator starts by placing its subject at the court of the Electors of Saxony, rulers of a slab of Renaissance Germany centred on Wittenberg. Cranach was their court artist from 1504 till his death in 1553. Perhaps these Saxon links explain his surprising popularity in Britain? Not only do his roots stretch back to our first Germanic invaders, but the present queen is descended from the Saxe-Coburgs, a subsequent branch of the Saxon royals. Brexiteers, take note.

During 50 years as a court artist, Cranach served three Saxon rulers and pictured all of them. These portrayals open the show. Frederick the Wise was Henry VIII-sized, with huge lamb-chop hair-work that made his face look as wide as it was tall. The next one, John the Steadfast, appears alongside his son, John Frederick the Magnanimous, in an intense diptych from the National Gallery. Two presences, one hefty and old, the other fragile and young, caged up by Cranach, side by side.

Finally there is Sybille of Cleves, John Frederick’s wife, swathed from head to toe in gold and pearls, and sporting one of those cartwheel-sized hats that became a Cranach trademark. However nude his Venuses, they never forget their big hats.

It’s skilled portraiture, but it doesn’t feel penetrative. You remember the clothes, not the characters. In matters of humanity, Cranach was no Dürer. Also, there’s a presence missing in these scene-setting salvos: Martin Luther.

Cranach was Luther’s closest friend in Wittenberg and his main portraitist. He churned out numerous likenesses of the great reformer. Alas, none are in British collections. So Luther’s gigantic presence has to infiltrate the show in other ways.

Alongside the paintings, there’s an engrossing selection of prints and folios. Cranach was an entrepreneur. His workshop employed more assistants than Damien Hirst, as it flooded the market with flying snakes. He owned various other businesses in Wittenberg: a chemist shop, a wine bar and, above all, a busy printing press. It is here that the “Innovator” named in the title pops into view.

The printing press churned out the works of Luther. The most startling example hereis a scary propagandist pamphlet in which the life of Jesus is compared with that of the Antichrist: the satanic pretender whose appearance on Earth was supposed to signal the countdown to the end of the world. Guess who plays the Antichrist in this apocalyptic leaflet? Yup, it’s the Pope in Rome, Julius II.

If you want to know why the Reformation really happened, forget all that stuff you were taught in school about a corrupt church and a return to basics. The scary literature pouring off Cranach’s press tells a different story. The end of the world was coming. And the Pope in Rome was its harbinger.

These curious conflicts give his art its peculiar flavour. He’s a loyal and busy court painter, yet he’s also a loyal and busy sidekick to one of history’s most radical reformers. The art seems to lurch from one side to another. It happens as well in the mythologies that come next.

Cranach is best known for his naked Venuses. They’re tall and wispy, and usually found in a forest, accompanied by a yelping Cupid. In the example here Cupid is crying because he has stolen a honeycomb and the bees are stinging him. Venus is completely and slyly nude, except for the aforementioned big hat. In a later version of the same composition, she covers herself half-heartedly with one of those see-through cloths that are a Cranach speciality. There’s something snakish too about her pose and the thrust of her head.

Modern audiences are keen to see only titillation in Cranach’s strange mythologies. But the artist was best friends with Luther. This cannot be eroticism. It has to be finger-wagging.

Cupid has put his hand in the honey pot and is now being punished. Venus looks more like a biblical Eve than a Roman goddess. The fruit tree above her head belongs in Paradise, not on Mt Parnassus. As for the big hat — it propels the action into the contemporary world. The sin of lust doesn’t belong to the past, says Cranach in his Venus and Cupid. It belongs to the here and now.

The final section of the show, the part dealing with modern reactions to Cranach, manages to ignore these moral complications. Instead, John Currin paraphrases the etiolated strangeness of Cranach’s nudes with an undressed housewife who belongs in a swingers’ party, while Raqib Shaw pays ornate tribute to Cranach’s ornateness with a trio of spangly pictures that feel like huge examples of posh jewellery in a shop window in Bond Street.

Perhaps Jenny Holzer, the word artist, should have been invited to produce something for the occasion. I’ve written a text for her already: They Just Don’t Get It.

Cranach: Artist and Innovator is at Compton Verney, Warwickshire, until Jan 3, 2021