An unexpected consequence of the Great Lockdown has been the opportunity to notice how much art there is on television. Not in actual art films, of course. Those are as scarce as ever. But in other places. Unexpected places. Especially murder films.

Last night I was watching a repeat of Endeavour, the prequel to Inspector Morse, and what should pop up at a crucial point in the butchery but Manet’s Olympia, repainted with a key suspect as the naked girl. Endeavour, the young Morse, tells us how the picture caused a fuss in the Paris Salon of 1865, how it affected Manet’s career and how Olympia was a popular name among prostitutes. Aha!

As the credits rolled, I grabbed the remote and headed for the 10 o’clock news. Something called Normal People was just finishing, with a shot of the central characters in an art gallery looking at an early Marcel Duchamp! It was that strange post-cubist painting from 1911, Nude (Study), Sad Young Man on a Train, which hangs in the Peggy Guggenheim gallery in Venice. Hah!

However, the apogee of TV’s unexpected ascent into art’s orbit during the Great Lockdown was an episode I caught among the repeats of a dark series called Vienna Blood. Set in Vienna at the turn of the 20th century, the world of Freud and Mahler, Schoenberg and Schiele, this laborious effort to transport the moods of Sherlock Holmes into central Europe featured a tall thin psychologist called Max Liebermann — just like the famous German impressionist painter! — and a short squat policeman called Oskar, as in Oskar Kokoschka. The two of them together were like the letter ‘l’ standing next to the letter ‘o’. But boy could they solve murders!

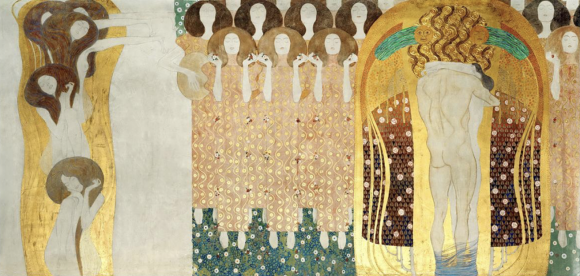

The key scene in the opening episode involved Max taking his fiancée, Clara, to an art opening at the Secession Building in Vienna, where they stroll towards a picture I had forgotten about: Gustav Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze, painted in 1901 to celebrate the composer. It’s Klimt’s most peculiar work, chiefly because so much of the centre is occupied by a cartoonish image of a gorilla with missing teeth. If anyone ever took a vote on the most unexpected presence in a modernist masterpiece, Klimt’s gorilla would surely be a leading contender.

In the programme, the painting starts suddenly to throb. Bits of it enlarge and zoom towards us, as if the gorilla has been chewing LSD. All of which is too much for another of the guests at the opening, a beautiful and distraught young woman, who starts howling and shuddering in a full-on mental collapse. Max rushes to her assistance and . . . you’ll have to watch the series. My ambition here is to stay with Klimt.

In my experience, he’s an artist who appeals to adolescent tastes. First you like him, then you grow out of him, like Salvador Dali, or art deco. In my early art history days, I was keen enough on his tubercular femmes fatales in their golden robes, the monkish moods, the theosophical babbling. It was only later that maturity prevailed. But the Beethoven Frieze was always in a league of its own.

It was painted for the 14th Secessionist Exhibition, which opened in Vienna in 1902. The event was devoted to the genius of Beethoven, and especially his great Ninth Symphony, which had been reworked by Wagner and Mahler. The sculptor Max Klinger made a huge sculpture of Beethoven, which sat at the centre of the show. I came across it once in the museum in Leipzig. It’s another ludicrous piece of Viennese over-the-top-ness — Beethoven with his shirt off, wearing Greek sandals and a wrap-around loincloth, sitting on a cloud surrounded by putti and a giant eagle. The Klinger was in one room. The Klimt was in the other.

In Vienna Blood you see the frieze on a set of screens in the middle of a gallery, but in real life it’s high up on the wall in the Secessionist Building, floating above us at divinity height. Also, it unfolds across three walls, with a strong sense of journey, though in Vienna Blood the focus is mainly on the gorilla scene in the middle.

It’s not actually a gorilla, although God knows it looks like one. It’s supposed to be the head of a giant serpentine monster called Typhoeus, the most wicked character in Greek mythology, an embodiment of evil. If you look carefully to the right of the gorilla you can see his giant wings and the abstracted coils of his snaking body. That’s the rest of him. As always with Klimt, anatomy isn’t a strong point. The dragon has broken into bits.

The three women to the left of Typhoeus are his daughters, the Gorgons, with Medusa and her snakes in the middle. Above them, looking like Cruella de Vil from One Hundred and One Dalmatians, are Sickness, Madness and Death. The three nudes on the right, meanwhile, embody Lasciviousness, Wantonness and Intemperance. Intemperance is the one with the fat stomach.

What, you are surely thinking, has this got to do with Beethoven? Good question. To understand — sort of — we need to look at the rest of the frieze as it unfolds around the walls of the Secession Building. On the left-hand wall there’s a line of wispy floating females drifting towards a tall knight in golden armour, who stands there with a huge sword. They are “genii”, embodiments of the human longing for happiness, and he is — yup — a knight in shining armour. They want happiness. He’s the guy who can deliver it.

Then comes the scene with the gorilla, depicting the terrible things that await us in life. Sickness, Death, Madness are ready to attack, with the toothy Typhoeus at the centre. Sickness is the hollow-eyed skull, top left. Madness, the crazy brunette with the dangling dugs.

So far it’s lots of bad news, and not much Beethoven. But that’s a wrong that the right-hand wall of the frieze sets out to righten with an ecstatic tribute to the Ode to Joy, the great climax of the Ninth Symphony. First, there’s a glorious chorus of singing angels. Then a golden couple locked in a volcanic embrace. What’s happening?

Klimt spells it out with a lyre-plucking nymph, representing poetry, and five big-haired dreamers, representing the other arts. Hang on everyone, he’s saying. The arts are coming to save us. Thus Vienna Blood delivers an artistic message I definitely wasn’t expecting.