Plenty of creative types have been shouting down from their balconies recently about the benefits of isolation. How the new rules of living are helpful and fruitful. How the absence of social distraction has allowed them to bring fresh energy to their work.

It’s nice that people think these kinds of things. Even though I find all this positivity irritating — without misery, what am I? — it is absolutely true that conditions of enforced isolation have, in the past, conspired in the production of significant art. Lots of it. In fact, I can say with some certainty that among the most helpful things we can do to an artist is to lock them up in a small room and throw away the key.

The most convincing evidence of the beneficial effect of lockdowns — a cascade of evidence — is what happened to Van Gogh after he cut off his ear. Having taken to wandering through the streets of Arles, raving, spurned in love, spurned in art, poor Vincent was put away by his brother in a mental asylum at Saint-Rémy in Provence. He went in May 1889. He came out in May 1890. So that’s a full year of separation: the single most productive year of his career.

In the 12 months living in a cell, with only one barred window to look through, Van Gogh produced 130 paintings and heaven only knows how many sketches and dabs. The asylum wasn’t full, so they gave him a downstairs room for a studio. It was about the size of my shoe cupboard. No coffee. No alcohol. No one came to visit, not even his brother. At night the other inmates kept him awake with their howling.

There were a few setbacks — he tried to kill himself by eating his paints — but time worked its magic and eventually he was allowed out into the countryside, where the exercise triggered another burst of pictorial genius.

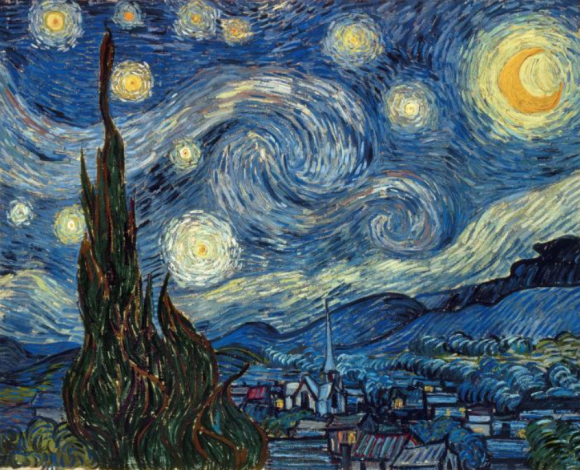

Among the paintings Van Gogh painted at Saint-Rémy are some of his best-known works. Starry Night is the view through his window at night, filled out and enlarged with ecstatic ideas about the cosmos. That’s how you think in isolation. Things seem bigger. More plangent. Irises, that gorgeous tribute to a swaying clump of blue flags, the most expensive painting ever sold when the Getty Museum acquired it in 1990, was painted in the asylum. So were the views through the window of the field outside his cell, which a gigantic south-of-France sun is showering with gold. For Van Gogh, isolation worked.

It obviously worked for the murderer Richard Dadd as well. Having killed his father, whom he suspected of being the devil, Dadd tried to escape to France, where he razored a passing local. So they locked him up, first in Bedlam, then in Broadmoor. What did he paint inside these notorious lock-ups? Fairies. The finest in British art! And the finest gnomes! Gathered in unruly crowds at the bottom of insanely detailed Harry Potter worlds.

A few months ago the Jewish Museum in London put on an exhibition of the work of Charlotte Salomon. It was a remarkable event. Salomon was a German Jew who died in Auschwitz, but who spent the first years of the war hiding in France, where she painted a secret autobiography called Life? Or Theatre?. It consisted of 769 paintings, dashed off at speed: a waterfall of anger, expression and invention.

Every page was dramatic, but the most dramatic was an astonishing pictorial admission that in France she had murdered her abusive grandfather, by poisoning him. Wow. The secret nature of the work, the isolation of its creation, gave it huge emotional heft. Isolation isn’t only an opportunity for freshness. It is a test of character, direction and substance.

One of the reasons I am a Picasso man in the great Picasso versus Matisse debate is because of how they spent the Second World War. Matisse, the older man, escaped to Nice, where he lived in the Hotel Regina. On a couple of occasions he appeared on the nationalist Vichy radio. Certainly he wasn’t a collaborator, like his one-time fauve allies Derain and de Vlaminck. And he wasn’t well. But unlike his wife and daughter, who stayed in Paris and joined the Resistance, he wasn’t a hero. Whenever I see a pretty Matisse stuck on a fridge with a magnet, I think of Vichy.

Picasso, meanwhile, stayed in Paris. At the time he was the most famous modern artist in the world. The occupying Nazis hated modern art enough to burn it and brand it decadent, but Picasso stayed, and taunted them with his presence. There’s a famous story, almost certainly apocryphal unfortunately, of a German soldier coming over to his studio and seeing Guernica, that great lament upon the fascist bombing of the Basques, propped up against the wall. “Did you do that?” the soldier asked. “No, you did,” Picasso shot back.

Compared with the isolation we are living through, his Parisian lockdown seems to have been a doddle. Somewhere or other he sourced the sea urchins, prickly as a crown of thorns, scattered on a plate in the magnificently glum Still Life with Skull, Urchins and Lamp, painted in Paris in 1943. It’s part of a powerful set of still lifes created during the occupation and soaked to the bones with its spirit.

Most still lifes in art are about what’s there. Picasso’s wartime still lifes are about what’s missing. Yes, he got a sea urchin somewhere and cut it into melancholy fragments, but everything in this insistently grey picture, from its bareness to its lighting, from its monochrome colour scheme to its black outlines, screams of captivity and deprivation. The lamp looks to be on its last legs. The skull is, was and always will be a premonition of death. Later on in his career as a political artist Picasso would make his opposition to war and fascism explicit. Here it’s done by implication. The spirit of his times has soaked into his art and made it great.

There’s a Matisse called The Lute, of a beautiful brunette in an ornate white dress, strumming a lute in a plush red salon. That was also painted in 1943.