There were doubts to be had about the exhibition of Gauguin’s portraits that has arrived at the National Gallery: issues, small and large, sprinkled between the show and its reception. A tiny one was, why have it at the National Gallery? Wouldn’t the National Portrait Gallery have been a more natural choice?

Then there were the noisy doubts about exoticism and sex and syphilis that always pop up when Gauguin is involved. He’s easy to mistake for the least woke artist in the canon, and some frothers-at-the-mouth will always keep mistaking him.

But the most troublesome issue here — for the serious art lover, at least — is why pick on portraiture as the focus for a Gauguin show? The paperwork for this event makes a big thing of it being the first such show, but it’s only the first because no one has previously thought of him as a portraitist. The alarm bells ding, therefore, and we have reason to suspect that it’s all a gimmick, an artificial agenda, like those exhibitions that look at Van Gogh and the Toenail, shows determined to wrestle big names into the gallery with whatever it takes.

All these issues were swimming around my bloodstream, triggering hesitations, until I reached the first vista and, boom, it all got blown away by a tremendous event. The journey is delightful from beginning to end. The show is filled with pictorial marvels by a painter whose every petal is a bouquet of beautiful brushstrokes. As for portraiture — it’s the perfect subject. It hits scores of nails on the head in Gauguin’s oeuvre. And it makes you rethink what portraiture is and could be. So, hands down, brook no argument, show of the year.

What portraiture is remains the governing conundrum. Many will assume it is enough to achieve a likeness. Someone paints somebody and it looks just like them, so that’s good, no? Not really. That’s just a beginning. Indeed, in another article, on another occasion, I could determinedly argue that great portraiture has rarely depended on likeness. What counts is where you go beyond physical resemblance. That is what separates the decent portraitists from the great ones. That’s where Gauguin comes in.

We have not generally thought of him as a portraitist because what he brought to the task took it to new places. Redrew it. Gave it a fresh and gripping future. The first room here is filled with self-portraits and, frankly, it alone is worth the admission. What a gauntlet of achievement. They span 20 or so years, with a couple more scattered about the show, and what they achieve is nothing less than the proclamation of a scaled summit. We knew Dürer was a great self-portraitist. We knew it of Rembrandt, of course. We knew Van Gogh was the third of the trilogy. Now we know that Gauguin was in that league. Which is to say, right at the top.

What’s remarkable is how he manages to make every picture a different event, with different things happening for different reasons. So the earliest self-portrait here, from 1885, when he was in Copenhagen, trying to succeed as a tarpaulin salesman to appease his wife’s bourgeois family, is among the more straightforward presentations.

He’s sitting at his easel, still young, with a firm stare, but wrapped against the Scandinavian cold in a coat that belongs on the Eastern Front. Look how thick it is, how cumbersome. How can he paint in that? And that’s the point. Smuggled into this straightforward image is a sneaky conceptual lament upon his exile, a set of social and psychological complications that nudge the picture into the realms of symbolism.

Elsewhere in the exciting opening room, the laments are less subtle. In the self-portrait as Christ in the Garden of Olives, he gives himself the reddest shock of standout hair in the show, just in case we miss who the sufferer is. And, in his masterpiece as a self-portraitist, painted in the year he left for Tahiti, 1891, he shows himself between two of his own artworks, a painting and a ceramic: The Yellow Christ and a strange pot in which he sucks his own thumb, like some kind of demented gargoyle from the Middle Ages.

The exact direction in which he’s trying to prompt our thinking here nonplussed this particular viewer. But your nerves will tell you immediately it’s somewhere deep and inner. That thumb in the mouth: what a scarily inventive gesture; what fuzzy human territory it burrows into to trigger its frissons. A personal agenda is being announced that is unknowable because no artist has previously announced it.

This sense that every painting is its own event never lets up in the show ahead. The works, about 40 paintings, dotted also with sculptures and ceramics and prints, are arranged in helpful thematic clusters that manage to trace a loose chronology. We see him starting out. We see him being an impressionist. We see him in Brittany, becoming the trademark Gauguin. We see him leaving for Tahiti. We see him coming back. Then going again. And, finally, we see him waving goodbye: a sad old man, wearing glasses for the first time, aged 54, about to die, having cut himself off in the most faraway spot on Earth, but confronting us defiantly with a laser stare, as if to say, I’m still here.

Away from his own face, Gauguin’s adventures in portraiture remain absurdly fruitful. A gorgeous selection of early portraits of his family — his wife, two children — are among the most tender portrayals of family dynamics you will ever see. There are lots of children in art. There are almost none who feel as tangibly loved and hugged.

His son Clovis, a little boy with girly hair, has fallen asleep under a big wooden beer tankard that seems to be standing guard over him, protectively. His daughter Aline has taken a fruit from a bowl, and the innocent act appears to be loaded with huge implications. As I said, every picture seems to invent a new ambition.

His Danish wife, Mette, is treated to an elegant tribute, Mette in an Evening Dress, from 1884, featuring expanses of pink satin of which Gainsborough would have been proud. Knowing what we know — that it was precisely this elegance that disappeared from their lives when he stopped being a stockbroker and started being a painter, and that its absence was why her family kicked him out of Copenhagen — shoots arrows of sadness into the beautiful portrayal of Mette.

The Tahiti sections of the show are just as gripping. What they do not feature is a sense of luxury or escape. Instead they are jaggedly confrontational, as if an angry prizefighter is picking quarrels in a Buddhist retreat.

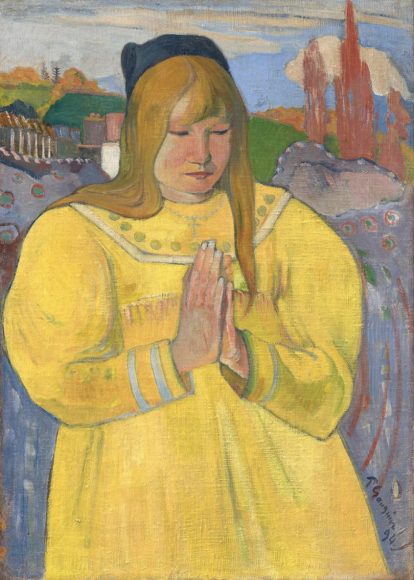

Tehamana, the first of his Tahitian “wives”, finds her face used to attack the French missionary system in a portrait that presents her in a shapeless Mother Hubbard dress of the kind imposed upon the natives by the missionaries. By surrounding her with fragments of her native religion, Gauguin is using clothing as a metaphor for colonial imposition. Portraiture has become a bullet fired at the church.

If you think that painting is confrontational, wait till you reach the carved wooden portrait of the local bishop, Monseigneur Martin, whom Gauguin casts as Père Paillard, the horned father of debauchery, devilish and scary, bestial and dumb. Martin’s crime was to criticise others for their liaisons while maintaining such liaisons himself. Gauguin, the volcano of creativity, the artist who worked in every medium, is using portraiture to exact a revenge. If you’ve ever doubted the power of art, feel the needles he sticks into his voodoo portrayal of Monseigneur Martin.

All this isn’t just gripping. It’s also a warning that we need to pay constant attention. What doesn’t look like a portrait with Gauguin is a portrait. And what is a portrait is also much more. The show has found a territory to mine that was always there, but never spotted. It’s full of gorgeous art. It’s a revelation on so many fronts.

Gauguin Portraits, National Gallery, London WC2, until January 26