Disease, insanity and death were the angels that attended my cradle,” Edvard Munch wrote, with typical cheerfulness, of his dark and poisonous childhood. Everything went wrong. His mother died when he was five. His sister, whom he adored, died when he was 13. Another sister went mad. His father was a religious lunatic who frightened him with tales of hell and the stories of Edgar Allan Poe. Why is his show at the British Museum so intense, nervy and unhappy? Because of all the above.

It’s called Edvard Munch: Love and Angst, but you’ll need to bring along a magnifying glass to find the speckles of love floating in the sea of angst. There are women everywhere, but love seems never to be the reason. Instead, it’s the emotions of infatuation that keep being aired: anger, jealousy, guilt, fear, possessiveness.

This is actually a print show. Its ambition is to celebrate Munch’s originality as a printmaker, and, in that field, there is much to laud. We see him first as a suspended head, staring straight at us out of the pitch blackness, like a sudden sight on a ghost train. It’s 1895. He’s 32. Yet lying across the bottom of the print, striking a vanitas note, is the arm of a skeleton. Only 32, yet already he fears death.

The skeleton, the blackness, the ghostly whiteness of his face, are obviously doomy. But what makes this such a gripping image is the eerie normality of the painter’s features. Short-haired and thoughtful, he could be a bank clerk or an insurance salesman. And it is precisely this lack of exaggeration that makes the self-portrait so haunting. Nothing is as spooky as the monster within.

The Bible blackness of the surrounding dark, meanwhile, reveals this to be a lithograph: only lithographs get as black as this. But the show’s opening display also includes woodcuts, etchings, drypoints, even mezzotints, the hardest technique of all. This sense of wild exploration is the event’s best gift. And it allows us to ignore the sometimes foolish imaginings about women that brand him, paradoxically, as a man of his times.

Munch churned out prints for 60 years. These days, it’s fashionable to appreciate his late work, and to seek to elevate it. Fortunately, the current show is old-fashioned enough to disagree, and focuses instead on his best work, the art he produced between 1895 and 1910.

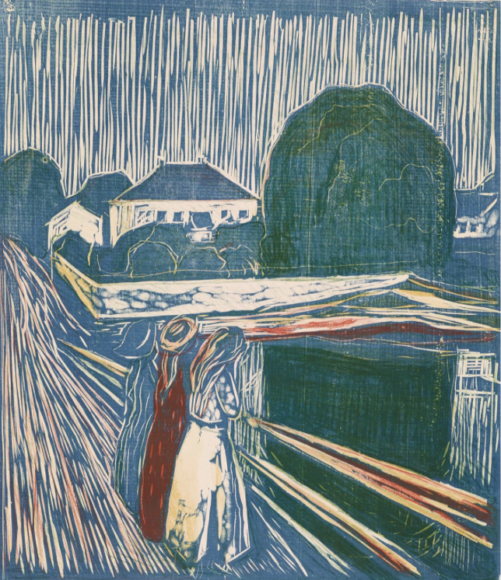

The Scream is here, of course. All his best-known images are here: Puberty, Madonna, Jealousy, The Kiss. All are presented in different printing techniques, because another of his pioneering impulses was to experiment with the emotional impact of colour by making different versions of the same image.

The version of The Scream we see here is another black-and-white lithograph, made in 1895. It was this widely disseminated print, rather than the original painting, that secured Munch’s fame as an international expressionist and a world-class pessimist. Interestingly, the text accompanying the lithograph makes clear that the skeletal figure on the bridge is hearing the scream, rather than producing it.

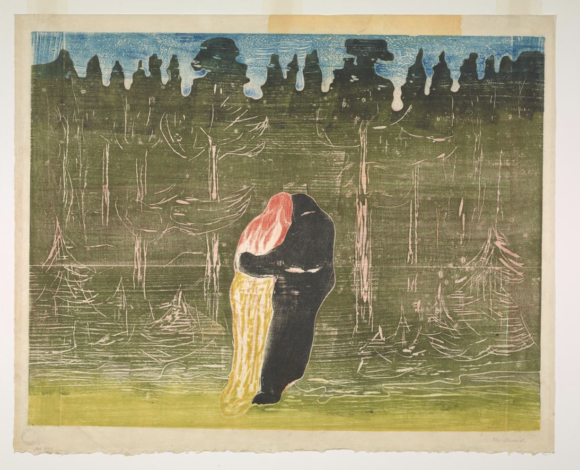

Jumping forward to his most adventurous print, the gripping image with the misleading name Vampire, we see a man burying his head in a woman’s chest. Her red hair cascades around him, trapping him, like alien plant life in an episode of Doctor Who. She’s naked, he’s not. So it’s an image of amorous despair, but the misleading title, added later by a tremulous pal, directs us towards the gothic horror when it ought to direct us towards the Freudian fear.

What’s really worth focusing on here is the technique. It’s so brave and inventive. Starting out as a lithograph, Vampire has also had a jigsaw of coloured woodcuts printed onto it in a medley of brusque techniques, all of which search for a sense of emotional rawness.

Another of the show’s welcome decisions is to display the original plates from which Munch made his different versions. Seeing these original plates — wood, stone, copper — prompts the kind of response that pilgrims must presumably have felt with relics. Something faraway and divine becomes tangible and touchable.

The original woodblock for Madonna is accompanied by two versions of the print: one in black-and-white, the other with added colour. It’s this added colour, the splash of red around the dreaming nude, that turns a harsh image into an intoxicating one.

The show is packed with invention. On most of its levels, it’s a fascinating journey. In its obsession with the femme fatale, it’s old-fashioned, immature and occasionally regrettable. But as a display of rule-breaking and artistic experiment, it’s exciting and revealing.