It is difficult to imagine a less helpful art book than this. Supposedly an exploration of the art of Edvard Munch, it is predominantly a ramble through the many aesthetic confusions of its notorious author. If you are interested in him, you might find things in here to savour. If you are interested in Munch, look him up on Wikipedia. It will be much more useful.

Knausgaard’s notoriety stems from the weighty six-volume autobiography he published between 2009 and 2011, which he self-effacingly entitled Min Kamp (Norwegian for My Struggle) and was, of course, an immediate auricular cousin of Hitler’s Mein Kampf. Begun in his late thirties, when he hadn’t actually done much yet, the sprawling Min Kamp was packed instead with harsh and unusually intimate portrayals of his wife and family, and it was their complaints about the betrayal of personal trusts that earned the series its notoriety. So popular was Min Kamp in Norway that 450,000 readers out of a population of 5m bought a copy. The international versions followed suit, with Zadie Smith insisting that she needed “the next instalment like crack”.

None of which bodes well. In any useful monograph about a great artist there is sprawling room for only one ego, and when an author is as determined as Knausgaard to force his own kamp into the spotlight, everything becomes a jostle for the microphone. The publisher of So Much Longing in So Little Space describes this effort as “art history, biography and memoir”, but even that jumbled shopping bag makes it sound more coherent than it is. A more accurate blurb would read: “Knausgaard follows his nose wherever he fancies, which is sometimes to Munch.”

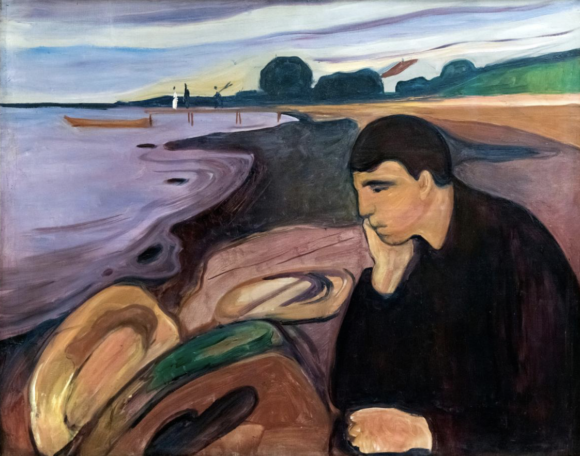

In any circumstance, Munch is elusive. Best known for the sequence of doomy symbolist paintings he produced in the 1890s, notably The Scream, one of the most famous images in the whole of art, Munch — born 1863, died 1944 — actually had a notably long career. The received wisdom is that after the fruitful decade of The Scream, his art fell into a repetitive decline and that the final 40 years of his contribution consisted mostly of what another of his Norwegian biographers, Stian Grogaard, describes on these pages as “basement drudges”.

Scrappy landscapes, messy portraits, slapdash nudes — anyone assigning themselves the rehabilitation of Munch’s late work has a battle on their hands. Putting it all in numbers, Knausgaard reckons that Munch’s posthumous reputation rests on 10 to 15 famous symbolist images from the 1890s, out of a lifetime ouevre of 1,789 paintings.

He has, therefore, taken on the occasional role of defender of Munch’s late work. It was in that capacity that he was asked to curate a Munch exhibition in Oslo in 2017, called Towards the Forest, in which he wanted to “exhibit unknown pictures on the premise that I believe it is possible for us to experience Munch as if viewing him for the first time”. It’s a decent ambition, and its implications dribble over intermittently into the present tome.

We begin with a lengthy description of a painting of a cabbage field, produced by Munch in 1915, a decade or so after his hot spell, in which we see some blue-green cabbages that are “almost sketch-like”, a dark horizon, some yellow flowers on the left, and that’s it. But for reasons that are never properly illuminated, Knausgaard insists that at the sight of this “magical” picture he sees “death”. “As if the painting intended a reconciliation with death, but a trace of something terrible remains.”

Hmm. Weakly reproduced on the next page, the painting in question surely intends nothing of the kind. I looked at it as Knausgaardedly as I could manage, with every fibre of my being hoping for flashes of Scandinavian angst, but nothing happened. It’s a poor painting, and everything that Knausgaard says he sees in it comes from him.

At least Cabbage Field, having successfully questioned the author’s eye, relates directly to Munch. Much of what happens from now on does not. Never missing an opportunity to go off on a tangent — any tangent — Knausgaard careers up mountain, down dale, on a chaotic journey directed, it feels, by that morning’s whims.

Suddenly, he’s in London, at the White Cube Gallery, where an exhibition has opened devoted to the German painter/sculptor Anselm Kiefer. Tracking Kiefer down to his studio outside Paris, Knausgaard is deflated to find the sprightly German dismissing 70% of Munch’s oeuvre as “weak”.

Suddenly, a handy Norwegian assortment of Toms, Dicks and Harrys — artists, writers and film-directors — pops up on the page to redirect the focus this way and that. In what I presume was an intentionally comic interlude, we learn about the time Knausgaard was invited to present a lecture on the occasion of Munch’s 150th birthday celebrations, and of the various delays caused by his children and his dog that stopped him from writing anything. Even the ticket collector on the train to the venue gets a mention, as does the chap installing fibre-optic at his house, who happened to call.

If you have not yet crack-piped your way through Min Kamp, this constantly distracted investigation of Munch can perhaps serve as a warning. It certainly gives you a sense of what to expect.

Harvill Secker £16.99 pp256