Good luck or bad luck? It’s a toss-up which of these two assessments best describes Bill Viola’s fortunes as he finds himself sharing an exhibition at the Royal Academy with the divine Michelangelo. Viola’s videos versus the drawings of Michelangelo. Is that one magpie or two?

The fact that this event is happening at all would seem to place it on the positive side for Viola. Michelangelo is probably the greatest artist who has ever lived. To share a stage with him is beyond the dreams of most. On the other hand, he was so brilliant, so powerful, such a dazzling draughtsman, that he cannot help but diminish anyone with whom he shares a platform. It even happened to the redoubtable Renaissance painter Sebastiano del Piombo when he popped up next to the master at the National Gallery a couple of years ago. Michelangelo chews up his co-exhibitors. Does he do it again to Viola?

I suspect you can intuit the answer. But, in the spirit of fairness, let us prolong the hesitation. In the past three decades, Viola has carved out a profitable niche for himself as a maker of uber-serious video art. His stentorious video epiphanies have weighty moods and seem always to address the biggest themes. The subtitle for the present RA show is Life Death Rebirth, and themes don’t get bigger than that. For those who accuse contemporary art of slightness, Viola’s contribution is a looming exception.

The first work you see here, towering above you in the grand upper galleries of the Royal Academy, is The Messenger, a blurry, naked figure materialising slowly in a gurgling expanse of dark blue water. Slowly it rises to the surface. Up, up, up. When it finally gets there, it takes a noisy gulp of air before slowly disappearing again, back into the flood, whence the whole cycle slowly recommences. Did I mention all this happens slowly?

I saw The Messenger when it was first installed in the nave of Durham Cathedral in the 1990s. In Durham, the lofty expanse of ecstatic water, with its air of baptismal sanctity, seemed to sing from the same hymnbook as the gothic spaces that surrounded it. Viola’s electronic blues rhymed with the stained glass in the windows, and a few lines of Philip Larkin forced themselves quickly into my thoughts: “If I were called in/ To construct a religion/I should make use of water/… My liturgy would employ/Images of sousing/A furious devout drench.” Viola in a nutshell.

Unfortunately, Viola doesn’t do nutshells. He goes for the whole War and Peace. The Messenger takes half an hour to complete its baptismal drench, and, removed from a sacred environment, the endless ascent and descent had me twiddling my thumbs after a couple of minutes, wishing desperately for something to happen. In a church, where the location does most of the work for it, Viola’s art can lease some profundity from its surroundings. In an art gallery, left to its own devices, it feels melodramatic, grimly pious and exceptionally long.

The next piece, a three-part video called the Nantes Triptych, lasts another 30 minutes, during which the slo-mo birth of a baby on the left is mirrored by the slo-mo death of an old lady on the right. In the middle, another floaty figure billows blurrily in a trademark douse of Viola waters.

If I were making a list of the least original symbols for the journey of life, I would pick as number one the pairing of a newborn baby with an expiring elder. It was already a cliché by the Middle Ages. Heaven only knows what that makes it today. The old lady, by the way, is Viola’s mother. They say never marry a writer, because sooner or later your life will appear in print, but, more seriously still, never have a son who is a video artist, in case he’s there at your passing, filming the departure.

An hour passed, two works down, and there are still 10 installations to go. It is simply not a good idea to show this many Violas in a row. The mood never shifts. Everything takes for ever. Summoning the concentration and sympathy that each piece demands becomes increasingly tough. By the time we reach the huge central gallery, where a canyon-sized installation called Five Angels for the Millennium wastes five screens and many acres of darkness on five brief pop-ups from the water, I have long since completed my own transformation into a Viola doubter.

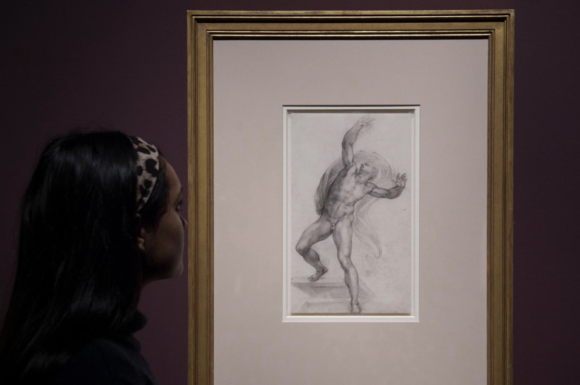

You’ll be wondering where Michelangelo fits into all this. Well, his most tangible task here is to offer an occasional respite from the tedium. Represented by just 16 drawings, which you happen across unexpectedly, he brings instantly superior levels of skill and humanity to these unbalanced proceedings. The organisers are keen to insist that they are not seeking to put the two artists on the same set of scales. Their hope is that Viola’s “spirituality” can help illuminate Michelangelo’s, and vice versa. Alas, what actually happens is that Michelangelo’s 16 drawings steal the show and successfully embarrass Viola’s 12 room-sized installations.

The first example of this is found on the wall opposite the Nantes Triptych, where a beautiful drawing of Mary holding the infant Jesus conveys in a few strokes what 30 minutes of heavy breathing, a live birth, a live death and three huge screens pulsing with portentous seriousness fail to convey on the Viola side of the meeting: the dark paradox of life.

Michelangelo’s infant Jesus, in a beautifully observed kiddie twist, wriggles round on his mother’s lap to look at her. She, however, stares past him, lost in private thoughts that we, on our side of the drawing, immediately sense pertain to the upcoming death of her son on the cross. The beginning and the end, the journey from birth to death, brilliantly implied, in a perfectly observed human moment.

This human understanding — lower-cased, born of sensitivity and watchfulness — is what Viola’s work lacks. His video melodramas are ponderously upper-cased: big, booming, glum and dark. There’s no range of tones. And where Michelangelo’s busy drawing of a Children’s Bacchanal is full of humorous details and wriggly human activity, Viola’s monotonous ripostes are always slo-mo, always stentorious.

As I said, the organisers here are keen not to compare Viola directly with Michelangelo. But they have made such comparisons inevitable. And sunk their guy in the process.

Bill Viola/Michelangelo, Royal Academy, London W1, until March 31