The Royal Academy feels like a different place. The opening of all the new galleries in the big rebuild has made it seem less like a single destination and more like a hub. The strong sense of artistic past that used to flavour the institution, the feeling Joshua Reynolds was watching you, has disappeared. These days, visiting the RA is less a pilgrimage to the fountainhead of British art and more a sampling of the duty-frees at Heathrow.

Certainly, the collection of drawings by Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele that has turned up in the Sackler Galleries brings a foreign taste to the shelves. Working together in Vienna in the opening decades of the 20th century — the great Viennese decades of the Secession, Mahler, Freud — here are two miserable talents who were miserable in different ways.

Klimt, the older man,was essentially a miserable romantic, one of those overwrought lovers of the past for whom the present would never seem good enough. In the first photograph we see of him here, he is wandering through an ornate garden in a kaftan: heavily bearded in the Byzantine manner and immediately difficult to take seriously. No artist, ever, should wear a kaftan.

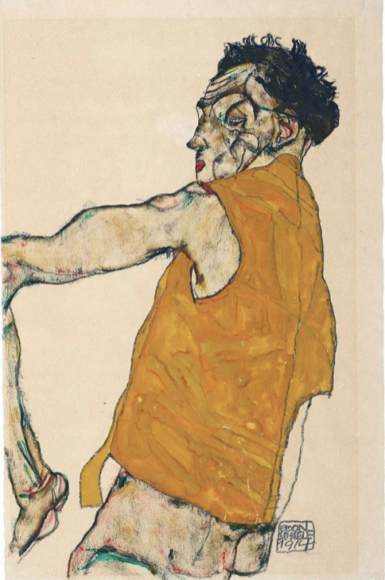

Schiele, by contrast, sports a crisp white shirt and tie, and stares out at us aggressively while twisting his hands into a claw. If you saw him in a documentary about serial killers, it wouldn’t surprise you. In Schiele’s case, misery is something he wants to share with us by targeting our nervous systems with his art.

The show ahead, of drawings lent by the Albertina Museum, in Vienna — the greatest collection of Teutonic graphics — confirms what the opening photographs suggest. Klimt spends the event in a dreamy state, imagining a world in which the clocks have stopped. Even the typefaces he chooses for the magazines he publishes look as if they began life as inscriptions on a Roman sarcophagus. Big capital letters. A sense of being cut into stone.

As a draughtsman, he was ostentatiously skilled. Among the early drawings we find here, mixed up with early Schieles, is a close-up of a dead Romeo from a Viennese production of Shakespeare. It’s just a head, slumped on its side, but the foreshortening is exquisitely right, and the strange angle we approach from seems to propel us into Romeo’s dying dreams. Klimt could draw like an angel, that’s for sure.

Most often, his subject was women, usually nude, usually as preparation for a portentous allegory he was planning. An old woman, drawn for The Three Ages of Woman, stands droopy and naked, a neat tuft of pubic hair poking out from beneath her stomach. I think it’s his mother. The beautiful line, with its touch of hesitation, makes something delicate and precious of her nakedness: a treasuring, not a stripping. It’s loving and lovely.

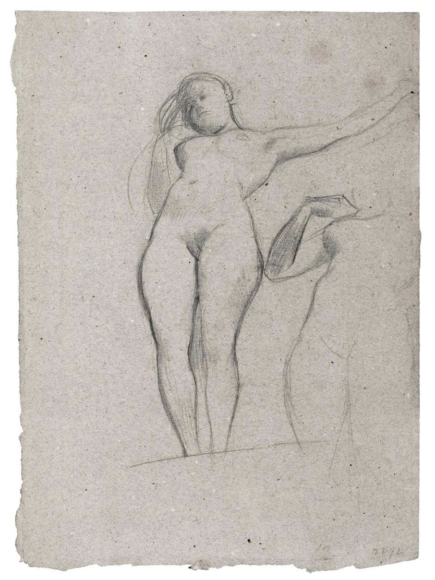

This same ambition to find a perfect line through a female body sees him tackling and retackling and re-retackling a nude slumped on her back with her arms outstretched who will eventually appear among the details of a pompous ceiling he was painting for Vienna University on the theme of Philosophy, Medicine and Jurisprudence. With Klimt, the draughtsmanship is usually impeccable. The thinking is usually dodgy.

A few walls later, after he had completed an inglorious transformation into a churner-out of society portraits of the rich wives of Vienna, even the exquisite line deserts him. The characterless wives he begins mass-producing, unhappy heads poking up from fluttering kaftans, become thoroughly interchangeable: kaftan-shaped mannequins.

All of which leaves the stage clear for Schiele to take this event by the nuts and give it a serious shaking. From the moment he bursts through the exhibition doors, Schiele is a one-man storm of rage, desire, cruelty, perversion and toxic psychology. Put him on a thousand couches, attended by a thousand Freuds, and you still couldn’t bring him peace. What an agitated presence.

You do not often see body hair in art. Since the Greeks, it has generally been a taboo detail. But both these Viennese bedroom-haunters are determined to display it: not as an admission of reality, but as an attack on propriety. Whereas Klimt’s pubic hair is sweet and coiffured, however, Schiele’s is as black and itchy as an infestation of spiders.

The first of his nudes we encounter here — probably a prostitute hired for the day — looks as if she has been thrown on a concrete floor. Her eyes are closed. Her nakedness is sprawled. She’s lost an arm and both her legs, a real-life Venus de Milo, butchered artistically for the nervy delectation of Egon the Ripper.

He was shockingly direct. Black-Haired Nude Girl, Standing (1910) shows a scrawny child-woman who looks about 15 — the Viennese age of consent at the time was 14, the caption tells us — whose Biafran thinness seems to accuse us of starving her. It’s a watercolour, painted mostly in blacks and whites, but, in a wicked touch, a touch of evil genius, Schiele smears four splashes of red onto her emaciated body: one for her lips, two for her nipples and the reddest splash for her labia.

He’s a spectacularly harsh depicter of women. And a spectacularly harsh depicter of himself. A series of self-portraits, done between 1909 and 1918 — the year he died, aged just 28 — thrusts us into the presence of a self-harmer with a mirror. As scrawny and angular as any of the women he painted, Schiele, in his self-portraits, seems to torture himself to save us the trouble. In a spooky close-up, he pulls down weirdly on an eyelid. In a full-length, he stands there screaming in a white robe, shaking his fists, a lunatic escaped from an asylum. As his finale, he sprawls in front of us, naked, and forces us to examine his bits.

I came out of the show feeling slapped about and targeted. It’s a rare feeling in art. But not a bad feeling. Indeed, it was bracing to be reminded of art’s potency as a conveyor of rage. It’s something we don’t get enough of these days.

Klimt and Schiele, Royal Academy, London W1, until February 3