The Industrial Revolution had a disfiguring impact on many aspects of British life. Geographically, it ruined the countryside and filled our valleys with smoke. Socially, it tore apart families and communities. Morally, it created a new chasm between the haves and the have-nots. Artistically, it prompted the arrival of the pre-Raphaelites and — worse than that — resulted in the ridiculous and belated career of Edward Burne-Jones. That’s quite a crime sheet.

How Burne-Jones has managed to maintain his rare artistic popularity on these shores is a great British mystery not even his hero, Merlin, could solve. If you look at his dates, 1833-1898, you see he was an exact contemporary of Manet and only a bit older than Cézanne. But if you look at his art, rather than his dates, it scarcely seems possible he shared the same planet as these progressive giants, let alone the same timeframe. While Manet and Cézanne were making art that foregrounded contemporary reality, Burne-Jones was clinking in full armour in the opposite direction, dreaming ceaselessly of damsels in distress and the handsome Lancelots who turned up in Camelot to save them.

This flight from the facts has traditionally been understood as a reaction to an increasingly mechanised Britain: a nation ruined by industry and commerce. But that doesn’t explain the seances, the fairy chasing, the Merlin hugging and the occult drivel spouted by Burne-Jones and his “master”, the equally ludicrous Rossetti. Yet instead of curling its toes at this moment and pretending it never happened, Tate Britain has organised its first Burne-Jones monograph for 85 years. In the process, the gallery seems also to be breaking some sort of record for the imagining and depiction of wispy young virgins in need of masculine salvation and a square meal. Look carefully and you may be able to tell some of them apart. But it won’t be easy.

He was not, of course, born Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, 1st Baronet. That’s what he turned into. He was born plain Edward Jones from Birmingham. But as his determined social climbing took him higher and higher up the ladder of privilege, he enlarged the Burne, after his aunt, added the hyphen and finally grew a Coley, after his mum. To understand him properly, to feel immediately the width of the gap that separates his art from the dank realities that spawned it, I find it helps to think of him as Ted Jones. That’s who he really was.

Indeed, one of the earliest droopy damsels in the show, Clara von Bork 1560, who was actually painted in 1860, is signed “Jones pinxit” — painted by Jones. It depicts a character from Sidonia the Sorceress, a notorious gothic novel by Wilhelm Meinhold about a Pomeranian witch who murders the men who cross her and fraternises intimately with the devil. In Meinhold’s absurd book, the devil disguises himself as a black cat, which is also how he pops up in Burne-Jones’s ludicrous picture, snuggling against the cascading Renaissance robes of von Bork.

The Tate’s attempt to take all this seriously can fairly be described as a good show about a bad artist. More than that, its organisers deserve a medal for keeping a straight face as Burne-Jones’s pseudo-medieval silliness mounts and mounts. Containing all his best-known pictures, and climaxing at its centre with a gallery filled with his biggest biggies — King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid and The Golden Stairs just about fit under the roof — it’s an attempt to find some shape in a career that consisted mostly of having the same girl playing different costume parts in a smorgasbord of increasingly loony escapes into the past.

Icelandic myths, Arthurian legend, Shakespearean fantasies, gothic horror stories, Germanic ghost tales, Ovidian love trysts — the further his sources took him from the Victorian world, the better it suited Ted Jones. While leching obsessively over wispy females was his most insistent fault, the stiffness of his touch is the first artistic problem to be highlighted by the opening room. Having gone up to Oxford to study theology and become a priest, he fell under the spell of Rossetti and decided, instead, to become an artist, with his Oxford pal William Morris. The two of them duly formed a secret brotherhood — called the Brotherhood. When they turned to art, there was lots of disgust with the modern world to drive them, but not much in the way of actual talent.

Later, Burne-Jones would gain a measure of fluency in his drawings, but the first ones we see here are as dense as a bramble bush. Every millimetre of Ezekiel and the Boiling Pot is overworked and claustrophobic. Although he later learnt to edit out some of this horticultural detail and to pass himself off as a sure hand, he was never properly capable of convincing summation or inspired breadth. What a cheek, therefore, to find among his early drawings an attack on Rubens, caricatured by Burne-Jones as a squelchy painter of fat nudes. A single gram of Rubens’s fabulous fluency would easily outweigh all the scratchy Burne-Jones mark-making gathered here.

The claustrophobia never really lets up. The whole show feels as if it needs to have the window opened so some fresh air can enter. Set in the relentless twilight of a flickering candle — gloomy, morbid, obsessive — his collected output does not feature a single smile or one moment of uplifted spirit. Even the most colourful of the big pictures squashed into the central space, Laus Veneris — based on a hysterical poem by Swinburne about the knight Tannhäuser, enslaved by love — features a Venus so bleak and droopy, she might more easily be the widow at a medieval funeral.

The brighter colouring in the picture, so unusual for Burne-Jones, is said to have inspired Lord Leighton’s glorious Flaming June, but the bipolar lassitude of its mood is pure Ted. Send all his hopeless droopers to the gym, I say. Get their hearts pumping with a bit of circuit training.

Perhaps because he was so obviously not a fluent painter — the effortful mark-making reaches a nadir in some gloomy mythologies done with watercolours that try to look like oil paints — he was notoriously keen to sample a wide range of different media with which to express his “artistic catholicism”. The first examples here are his stained-glass windows, an art form that suited his melancholy and his regressiveness.

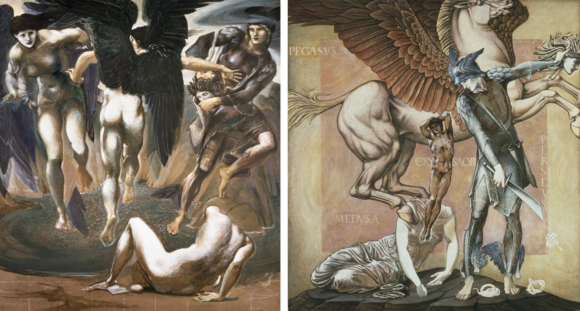

Today, there is barely a church in Britain that does not have some chancel illumination inside it by Morris & Co, where Burne-Jones was ecclesiastical designer in chief. A pair of windows from the V&A see him taking quickly to the world of simplified outlines and glum expressions. Later in the show, we see pianos decorated by him, and a set of Arthurian tapestries, lent by Jimmy Page from Led Zeppelin. The biggest decorative effort, however, went into the telling of the story of Perseus and Andromeda, recast here as a pair of Arthurian lovers taking on Medusa and the dragons in a sequence of panels commissioned for the drawing room of the future prime minister Arthur Balfour.

Although the central gallery, with its parade of greatest hits, is the show’s most spectacular room, the most revealing is surely the smaller gallery next door, filled, unexpectedly, with contemporary portraits. Hidden beneath the ornate details of his mythologies and legends, Burne-Jones’s shortcomings as an artist are easier to miss. With his portraits, everything becomes self-evident.

His poor wife, Georgiana, who spent their long marriage putting up with his lechery and his infidelities, looms up suddenly like Morticia from The Addams Family. Pale enough to be suffering from tuberculosis, or perhaps she has just seen a black cat, the poor woman holds up the book she was forced to read to him to soothe him while he painted.

Stripped of costumes, no longer pretending to be witches and sorceresses, the unfortunate women in Burne-Jones’s life are as convincingly human as the cutouts at a ghost train. Happy Halloween.

Edward Burne-Jones, Tate Britain, London SW1, until February 24