Until I swooned my way round the Thomas Cole exhibition at the National Gallery, glued to the walls and recurrently in ecstasy, I never suspected that Bolton, Lancashire, was such an important location for American art. In matters of art, folks, Bolton made America great.

Cole was born among the failing satanic mills in 1801, and when his desperate father packed the family onto a transatlantic packet in Liverpool in 1818 and set sail for the Promised Land, it triggered a set of circumstances that were to fill American art with thunderous hopes and yawning disappointments. In matters of art, Bolton made America troubled, complex and mystical.

Cole is renowned as the founder of the Hudson River School, a gang of 19th-century painters who worshipped the new landscape and recorded it with religious fervour. Hudson River School pictures are never content to collect the thrilling vistas of America. God seems always to be watching as well, and judging.

The show opens with a couple of unfair rooms in which some early pictures by Cole are joined by a superb selection of whoppers by Turner and Constable. I say “joined”. “Overwhelmed” would be more accurate. Turner’s Snow Storm: Hannibal and His Army Crossing the Alps is one of the master’s greatest moments, a huge, swirling blizzard of climatic action in which the entire sky appears to be being sucked down a cosmic plughole.

Constable’s Hadleigh Castle shows the old ruin waking up in the morning after a mighty storm. All around, the white light of dawn is trying effortfully to force its way through duvets of thick cloud, like an unsteady weightlifter swaying at the top of a clean-and-jerk. What a tremendous capturing of a devilishly difficult atmospheric effect.

This is Constable and Turner at their very best. In reply, poor Cole, at the start of his artistic journey, can only manage a gnarled drawing of a tree and a view of the Catskill Mountains on a Sunday morning in which the Hudson River winds its way towards the horizon through patches of mist. Sizewise, compared with the Turners and the Constables, it’s a modest thing. But in terms of big emotions and religious heft, it is trying desperately hard to be a descendant.

Having been brought up a Calvinist, Cole saw nature as God’s miraculous gift to us wretched humans, and the spoiling of that gift became his chief American subject. As a teenager, he had witnessed the Luddite fires with which a freshly unemployed factory class in Lancashire sought to wreak revenge on the satanic machinery taking its jobs. By upper-casing the Bolton origins of his world-view, this resonant show explains that prickly feeling you get in front of the best American landscapes of Thomas Cole. This is art speaking the international Esperanto of despair and the universal sign language of broken hopes.

It leads to some weird imagery. The Garden of Eden, painted in 1828, transports the biblical story of the Fall of Man to somewhere that looks exactly like New Hampshire, with the famous White Mountains looming in the distance. In the foreground, surrounded by pink crystals and displaced hummingbirds, an unlikely Adam and Eve, naked and trembling, beg God for forgiveness for the terrible sin they are about to commit.

An extraordinary painting called Titan’s Goblet, from 1833, is even stranger. It shows a gigantic stone cup perched on the top of a rock that once belonged, we are encouraged to surmise, to a race of giants living in these same New Hampshire hills. All that remains of them today, according to Cole, is the oversized goblet, which nature is busily repurposing as a mountain lake. That’s what happens to decadent civilisations. They rise. They fall. Nature reclaims them.

Cole’s masterpiece in this despondent genre is a series of five large paintings called The Course of Empire, which tell the unfolding story of a civilisation that comes and goes. It all happens, symbolically, in a single day across the same landscape. In the early morning, the pioneering civilisation builds itself a Stonehenge to thank the gods for their bounty. By mid-morning, there’s a town there, waiting to grow. By noon, the town, has become a frantic metropolis crowded with orgiastic fun-lovers. By teatime, the skies have turned black and the disappointed gods are destroying the city with cosmic storms and Luddite fires. In the final scene, nature has regained the ruins and everything is peaceful again.

It’s a spectacularly bleak vision. And it could not have been aimed more directly at America had I Love New York been scratched onto one of its broken columns.

Cole’s pessimism turns out to have had artistic legs. It isn’t only Francis Fukuyama who learnt to fear the future from him. That smart contemporary American painter Ed Ruscha can also style himself a disciple. Inspired by The Course of Empire, Ruscha has produced a set of views of modern Los Angeles animated by the same civilisational fears and doubts. And, in a nimble move, the National Gallery has put them on show in a separate but pertinent display.

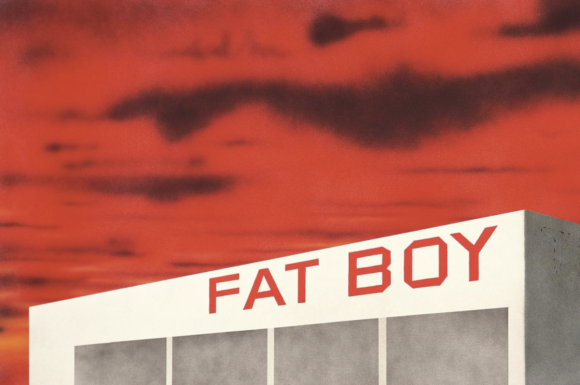

Ruscha’s response is in two parts. In 1992, he painted five thriving LA businesses — a hardware store, a telephone exchange, a chemical lab, a business school, a tyre shop — in his trademark minimalist style. So minimalist are the picturings that all you see is the tops of the buildings and the signage advertising their purpose. To make them even sparer, they were done in black-and-white, with only the sky above supplying some organic relief from the harsh geometry of the city.

In 2005, in part two of his effort, Ruscha returned to the same locations and produced five more pictures, in colour this time, but the same size. All are now being shown together, one above the other, like the TV presentation of University Challenge, a display strategy that forces us to compare them. And I’m afraid it’s all bad news.

The business school has become a faceless office with a barbed-wire fence around it. The chemical lab has become a clothing store called Fat Boy, and the sky above has turned an apocalyptic red. The hardware store is now something Korean, covered in urban graffiti. While the telephone exchange isn’t even there any more. It’s been knocked down. A dying tree and a harsh concrete pylon mark the spot. Hello, modern America. And goodbye.

On the Serpentine Lake, in Hyde Park, London, the notorious land artist Christo is also supplying us with concrete proof of a terrible decline: in his case, in the quality of his art.

Back in the 1980s and 1990s, Christo’s outrageous plans to wrap entire buildings in bright fabrics, or to span impossible lengths of canyon with coloured curtains, resulted in some truly spectacular sights. There was something genuinely ambitious and hardcore about his efforts. In particular, the wrapping of the Reichstag in white cloth, in Berlin in 1995, was an act of creative chutzpah with huge political resonance.

That was then. Today, Christo has become a novelty act pumping out cheerful sights for summer visitors to London. For his Serpentine show, he has erected what appears to be a ziggurat of pink oil barrels in the middle of the lake. It’s actually a pre-constructed scaffold, clad in a layer of fake barrels, made to order. So it’s just a jaunty illusion, with the artistic heft of a bouncy castle.

Thomas Cole and Ed Ruscha, National Gallery, London WC2, until Oct 7; Christo’s Mastaba, Serpentine, London W2, until Sept 23