The other day, the last male northern white rhino in the world died in Africa. He was called Sudan. You probably saw the news report. His subspecies had been wiped out in the poaching boom of the 1980s and 1990s to make Chinese “medicine” and dagger handles in Yemen. A few months earlier, you might have watched Blue Planet II and seen the baby whale, killed by plastic waste, being carried hopelessly through the waters by its mourning mother. Like me, you would surely have shed a tear.

It is against this backdrop of animal diminution and human enlargement, where the humans commit the sins and the animals pay for them, that Turner Contemporary, in Margate, has chosen to mount Animals & Us, an exceptionally timely show that probes the way in which artists through the ages have depicted animals. Why they have depicted them. What they are trying to say with them.

I say “probes”. Modern curators are generally keener to find smart visual connections than to deepen our expertise. Today’s theme shows can more accurately be said to skim a subject than to probe it, a process I have described in the past — cruelly — as playing snap through the ages. That said, snap can be fun. And with the current round of animal troubles supplying a tragic and profound background to all this, Animals & Us stands out as an especially relevant display.

We begin with cave art and the important observation that the earliest paintings we know are depictions of animals traced onto the walls of our subterranean “temples” and underground shelters. No one is certain why they were put there. All we can be sure of is that it was a matter of life or death. Otherwise, why journey miles under the ground, deep into the unknown, in total darkness, risking so much danger, to paint a bison on the walls of Chauvet Cave? It must have been crucial.

The present organisers cannot, of course, get any actual cave art into Turner Contemporary — though Margate does have its mysterious Grotto! — so we have to make do here with a punchy wall text and a small vitrine filled with bits of early animal pottery from around the world. It’s the barest of indications, but at least the centrality of animal imagery in human art is immediately acknowledged.

The religious issue is also briskly addressed. From Egypt to China, when early artists imagined their gods, they gave them animal forms. A Chinese cat. An Indian horse. An Egyptian bird-man. It’s as if the animal kingdom was instinctively understood as a holier world than our own.

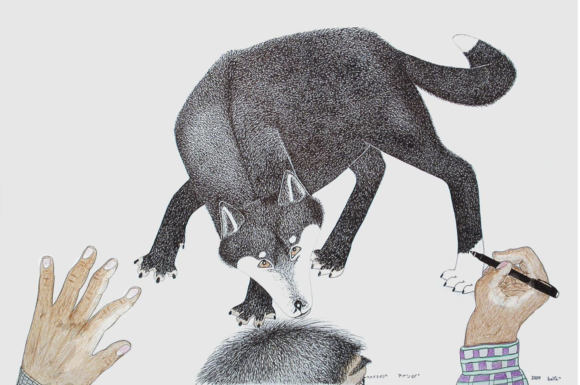

Heaven, however, needs a hell, and another of the demanding roles handed out to the poor old animal in art was to represent our basest and least controllable instincts. In Raqib Shaw’s gorgeous but crazy scene of a fantastical Indian palace being overrun by the Monkey King and his followers, it is clear that the monkey’s job here is to stand in for the regrettable lunacies of humanity. At the other end of the show, Paula Rego’s fierce and violent red monkey is a surrogate for an abusive husband in a fractured relationship.

So it’s all rather tricky. From the start, animals in art have been presented in a fashion that indicates both our dependence on them and our separation. Instead of seeing ourselves as part of a unified natural world, a glorious natural kingdom that we share, we have generally cast ourselves as the pashas and the animals as our back scratchers.

Which is why the undervalued baroque portraitist Gilbert Soest gave us such a fascinating portrayal of Sir Thomas Tipping and his dog c1660. The unpleasant Tipping looks down his nose at us, with typical Restoration haughtiness, while the dog he holds gets roped into the dog’s usual symbolic role in art, which is to represent fidelity. But there’s a twist. A dark one. The way Tipping clutches the spaniel’s head and points it at us is too firm. There’s an edge of cruelty to his gesture: a deliberate forcing. What looks like a typical baroque portrait has something nasty to say about the relationship between animals and humans. We control; they suffer. It’s the root of the tragedy.

The show is a typical Margate mix: art from the past, flooded out in the end by contemporary examples. The usual Margate locals are here, Turner from then, Tracey Emin from now, both giving us lovey-dovey depictions of cats. (I think it must be written into the contracts at Turner Contemporary that Joseph and Tracey appear in all the mixed shows.) Another local, Paul Hazelton, contributes a pair of beautiful drawings so small, you need to press your nose against them to decipher them. One shows Dürer’s famous rhinoceros in a ghostly distance. The other remembers Sudan in his final moments.

To its credit, contemporary art is the first art that has ever sought actively to criticise and adjust the exchange between animals and humans. After a short introductory section, in which we speed-read through the story so far, the exhibition settles down to its main task, which is to display how a variety of contemporary artists, celebrated and obscure, have tackled the subject.

Sprawled across the first room, slumped on the ground like a drunk in a doorway, is a giant giraffe, homemade by Laura Ford: stuffed, lumpy and sporting the absurd costume of a Regency dandy. She represents the first giraffe to be seen in Britain, a gift to George IV from the Pasha of Egypt, which arrived at Windsor Castle in 1827 having been carried across the desert strapped to a camel’s back, then chained up for the long sea voyage across the Mediterranean. The poor creature lasted two years in the king’s hopeless care before tragically expiring. Ford’s sculpture is both a lament on her fate and an accusation. The ghost of Georgian England — fat, gouty, impotent — looms over the fallen creature. You can’t see him, but he’s there.

It’s a powerful moment, as witty as it is piercing. Most of the contemporary art collected here is notably well chosen and feels genuinely restorative. Another triumph is the amusing video piece by Marcus Coates, produced in Fogo Island in Newfoundland, where the last great auks were hunted to extinction in 1844.

Coates travelled to Fogo in 2017 and persuaded its mayor to read out a public apology to the auks for engineering their extinction. The video cuts from the committee room in which the text is being agreed on — with lots of local prickliness about the wording — to the Fogo dock where the unlikely mayor with a megaphone blares out his apology across an empty sea. So it strikes a Dom Joly note, and there’s an air of absurdity about the hopeless apology, as there usually is with the excellent Coates.

Well done, Margate Contemporary. You have found a theme that matters and produced a show that is inventive, entertaining and emotional.

Animals & Us, Margate Contemporary, until Sept 30