A few times in my life, I have felt so cold that it hurt. There was that trip to Kazakhstan, in 2006, where the temperature dropped to -44C and the contents of my nose began snowing onto the microphone as I tried to present a film about performance art. There was New York, where the January wind that comes razoring down Lexington Avenue cut me in half as I tried to get to an interview at Grand Central station. And then there was Margate, where I went recently to see Tracey Emin’s new home. Blimey, Margate is nippy.

As I came onto the seafront, a giant icicle of wind slammed me against an amusement arcade and began drilling into my forehead. The beach was on the move, too, and got into my eyes. Why would anyone move here, I fretted, as I struggled from doorway to doorway, searching for Union Crescent.

Emin’s new gaff is opposite an Anglican church that has been turned into a mosque. The cross has been taken off the spire, and all exterior signs of Christianity have been brusquely redacted. Opposite the mosque, in what used to be a printworks, a legion of hi-vis workers is busily turning 30,000 sq ft of industrial ruin into Emin’s new studio, and her dinky new abode.

Having yanked myself along the seafront railings, I get there 10 minutes late, only to see Emin herself clambering unsteadily out of a big black 4×4. I know that gait. That’s her day-after-the-night-before walk. What happened? Through slitted eyes she recalls that she was at an opening last night, at the White Cube gallery, and that today she is feeling a little peaky. The new place is this way. Through that large wooden gate.

Inside, in what will be Emin’s huge sculpture studio, an important meeting is taking place involving the construction team, her production manager and the architect, all of whom are arguing about the position of a manhole cover. The meeting is supposed to involve Emin as well, but having found a warm corner of the table, and laid her head down on her hands, she falls into a coma and is with us only in spirit. An assistant suggests I do the tour instead, and off we stomp in hi-vis yellow to explore Emin’s summer palace.

At the back, a pigeon-splattered factory floor is being converted into a painting studio: tall, be-columned, with that ecclesiastical vibe you get in cool warehouse conversions. On the other side of this fabulous space, the London art dealer Carl Freedman is going to open a new gallery. Is that the same Carl Freedman who used to be Emin’s lover? It sure is. Later that week, when we reconvene in London and the conversation switches to old boyfriends, Emin cheerfully insists she is still on excellent terms with all of them. What? Even with Billy Childish, whom she accused of being stuck, stuck, stuck, and in so doing christened the Stuckists, that demented gang of artistic losers who love bashing modern art? “Yeah, me and Billy are still in touch.”

Up the stairs, on the left, is a double-height vestibule that is going to be the main entrance to the gallery complex. “That’s your wow factor.” Over there is a new drawing space. And that bit here, the Georgian bit with a courtyard in the middle, that is where the sultana of Margate is going to live. Her new home.

With Emin still snoozing, and so much still to see, it is suggested I should go and grab a cup of coffee, take a look around Margate, and come back later to finish my tour of all this battered concrete. So off I stumble, toes ready to crack from the cold, to a place in the old town that looks like the inside of a ship’s cabin. I have barely had time to order a crab sandwich when the phone goes. Emin’s awake. She’s having her photo done. Come right back.

The sleep has done her a power of good. Her gypsy eyes are twinkling. The words are cascading out. And getting a question in edgeways is a test as she leads me through the dripping maze of her new empire. This is going to be her library. Double height, like a gentleman’s library, with books at the top of a ladder. These are the guest quarters, for visiting artists. That’s the Juliet balcony, which will look down on the courtyard. And underneath, that’s going to be a winter garden, dedicated to her dad, who was Turkish Cypriot. It’s going to be tiled in the Turkish manner, with orange trees and water features. A mini Alhambra, no less.

All this will be ready in 72 weeks. You mean 100 weeks, I interject, having had plenty of experience of builders. No, 72 weeks. Everything is precisely on schedule. But now that she has come back to life, she is noticing scores of things that need to be dealt with. Why don’t I get the train back to London, and we can meet later that afternoon in her studio in Spitalfields?

But I haven’t found out yet why she’s leaving London. That will happen, right? Yes, it will.

Later, the assistant calls again. Would I mind making it another day? Emin has so much to discuss with the construction team. Of course she does.

This is Wednesday. Fast-forward to Friday and we’re finally ensconced in her London studio, warm as toast, surrounded by a ring of new paintings she’s working on. She may have turned up in Margate like the Emin of old, reeling from the drink, but I thought I noticed an unexpected maturity in her. I’ve been trying to work out why she seemed different. Whatever the Margate move is about, it seems to involve a lurch into wisdom.

At first, the conversation goes swimmingly, and we make small talk about her plans. But then I make the mistake of asking her about sex. And of doing it in a blokish fashion, with the hint of a smirk on my lips, because we blokes are not very good at talking maturely about sex. In the past, Tracey, your work seemed usually to be about sex. Has that changed? Have you now entered a post-sex phase?

It’s like prodding a cobra with a sharp stick. Her eyes narrow. Her voice lowers. And she goes for me.

“I don’t think that is very funny. When you get to 55, after you’ve had your menopause, things are different. The world is different. I do not have to be poked by someone. Because I’m not married. I’m not in love. I’m not there to make someone happy. I’m not there to fulfil someone’s needs. I’m there to fulfil my own needs. And shagging someone, just because I can’t cope with being on my own, would not make me feel good. I prefer to be alone, within my own sovereignty, within my own environment, choosing what I do and how I do it.”

The lecture concludes with a noisy silence.

“That’s told me,” I mumble in sheepish apology.

“Yes, it has,” she agrees, like a matron in a boarding school chastising a naughty schoolboy.

Dark-eyed and olive-skinned, still youthful, still glistening with gypsy gold — she’s Romani on her mother’s side, as we found out when she appeared on Who Do You Think You Are? — Tracey Emin, 2018, has a new softness to her. I’m not going to call her matronly, because she would get her gypsy ancestors to kill me for that, but there’s a fraction more of her, and the tiny widenings have created a more welcoming air. On the surface, at least, she is not as fierce as she used to be.

That said, it is only now, when she is not here — as I write this, she is flying to Australia to unveil an ambitious public sculpture commissioned from her by the city of Sydney — that I feel my nerve returning and want briefly to return to this question of sex.

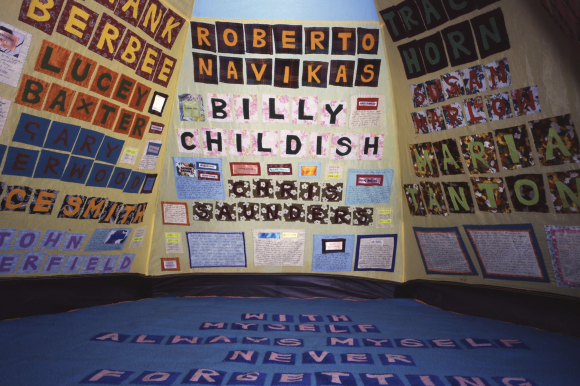

The studio we are sitting in is packed with nude versions of her — painted, sculpted, photographed. In her art, she has never had any difficulty getting her kit off. And her best-known works have a definite sexual presence to them. There was that infamous tent embroidered with the names of everyone she had ever slept with. And the unmade bed at the Tate with its crumpled panties and its used condoms. So yes, I think it is fair to say that issues of sex have played a notable role in the shaping of our perception of Tracey Emin.

But — and this is a big but — it is also fair to say that with Emin people see what they want to see. The tent was not actually embroidered with a list of 100 lovers. Her lovers were named, but so was her grandmother, twin brother, sleepover friends and other children. Ultimately, it was a work about warmth and intimacy.

I first saw it in a big show of YBA art in Minneapolis, of all places, where you had to crawl into the tent with a torch. You shone your light around and the names would loom out of the darkness like cave drawings. Also embroidered onto the walls were references to the twin foetuses she had lost in an abortion.

So no. It wasn’t a work about sex. It was about snuggling up and feeling safe, about intimacy and closeness, about lying in the dark imagining things and remembering people. Tracey Emin is important not because she is shocking, but because she speaks from the heart. And the fact that people who recall the tent usually do so with a smirk — it was destroyed in the Momart fire of 2004 — tells you more about the world we live in than it does about her.

Speaking of the world we live in, why is she really going back to Margate? What happened?

It all goes back to the sabbatical she took in 2015. She had been planning a break for years. There had been too much travelling. Too many distractions. So she decided to go down to her house in France for a year and paint. No exhibitions. No interviews. Just art. Unfortunately, the fates, chiennes méchantes that they are, were having none of it.

In May 2015, a month before she was due to start her break, her mother, Pam, was diagnosed with cancer. The fates had decreed that her mum’s fatal illness, and her rejuvenative year, should coincide perfectly. “So there you are. Couldn’t get it more spot-on.”

As it happens I know a bit about Tracey’s mum. Back in 1999, around the time the notorious bed was being shown for the Turner prize, I produced a film called Mad Tracey from Margate, and in the making of it I met the entire Emin clan. Her dad. Her twin brother, Paul. Her mum. Pam would turn up at shoots oozing a delightful mix of acceptance and excitement. Whatever her daughter was up to, however shocked everyone else was by it, it was just Tracey being Tracey. So that was fine.

Before I even met Pam, she played a significant role in my own TV career, because in 1997 I was asked to make a short film for Channel 4 to be shown on the night of the Turner prize. It was prompted by an article I had written for this paper in which I argued that painting was no longer the only way to make art, and that other methods — installation, neon-work, performance — were also valid. It was intended as a defence of Tracey Emin.

I made sure, therefore, that she was invited onto the panel of art-world worthies assembled by Channel 4 to discuss the matter, live on the telly, after my film was shown. The great and the good were there — the philosopher Roger Scruton, the art historian David Sylvester. To mark the seriousness of the occasion, I even wore a yellow bow tie for the first time.

For a few minutes, we talked earnestly about the death or otherwise of painting. Then Emin, who had managed to get herself well and truly pissed on Channel 4 hospitality before she sat down, began clawing at her microphone. “I’m leaving now,” she hiccuped. “I wanna be with my friends. I wanna be with my mum … You people aren’t relating to me now. You’ve lost me.” And out she struggled. It was brilliant TV. But having floated the argument about painting specifically to defend her way of working, it was galling to have it shipwrecked so spectacularly. If you watch the clip you’ll hear me plaintively whispering “Bye, Tracey” as she leaves.

So yes, I know about her mother. And to get back to the events at hand, I know how pressingly Pam’s illness would have affected Emin, and how black those months in France must have been. But having defended her right to make art in any way she chose, it was surprising to see her becoming the ever-so-painterly painter, whose work, in various stages of unfinish, now surrounds us in her London studio.

In France, in her sabbatical year, all she did was paint. “It’s in the middle of a nature reserve,” she explains of the house she bought 10 years ago in the hills of Provence between St Tropez and Toulon. “There are no neighbours. I don’t speak any French. I don’t have any social life at all. None. I just paint all day in my pyjamas.”

Also in France, she realised she needed to refocus and take her work more seriously. “My God, have I f***** around. I said this to Nick Serota. I said I can’t believe that people like Nick have had faith in me. When I think about when I was younger … what were we doing!” So she immersed herself in painting and lifted the phone for no one. Every two weeks, she went back to Margate to hold her mum’s hand and watch the illness progressing. A painting on the wall depicts a Victorian-looking woman carrying a box. The woman is Emin and the box contains her mother’s ashes.

Pam died in 2016. Emin was there, holding her hand. After the funeral, she went home with her mother’s remains. “Have you ever carried a box of ashes?” she says. “It’s so f****** heavy.”

Often in her paintings, she covers up the first image. “It could end up with 10 layers of paint.” But sometimes she cannot bring herself to touch them. “It might not be any good as a painting, but I just can’t paint over it. It can tell me something I didn’t know. So it’s like going to a fortune teller.”

Her mother died at 1am. She came straight back to London, had a couple of hours of sleep, packed a bag and took a train to Paris, where she checked in at the poshest hotel in town, the George V. “The bed was enormous. All night long I could feel my mum holding my hand and all I kept thinking was that my mum would be so proud of me being in the George V, instead of being curled up at home in a ball, crying on my own.”

She went to the Rodin Museum. The Louvre. All the shows. “Art is my partner. And in a time of grief, you want to be with what is closest to you. Because I’m alone, I had to go to what I wanted.”

It was then she decided to move back to Margate. The visits to the hospital to see her dying mother had woken up an attachment to her home town. Going back to reminisce was not enough. “I think going home, in philosophical terms, is one of the most humble things you can do. When my mum was still there, Margate was still home in my head. And I suddenly realised that wasn’t there for me any more. And I didn’t like it.”

As an artist, the idea of waking up in Margate and going for a walk by the sea appeals as much to Emin as it did once to Turner, who spent many a happy January shivering on Margate sands. “The skies over Thanet,” Turner wrote to Ruskin, “are the loveliest in all Europe.”

Besides, Spitalfields isn’t what it used to be. “You know how, two days before Christmas, you’re still running around trying to buy everyone presents? Well, London is like that. And that’s not what I bought into 20 years ago when I came into this area. If I want that, I’ll go up to Bond Street.”

I hear you, Tracey. And I think I understand. But for heaven’s sake make sure you pack your long johns.

Tracey Emin’s I Want My Time with You, 2018, will be unveiled at St Pancras International station on April 10