Mark Rothko said a good thing once. He said: “There is more power in telling little than in telling all.” Rothko wasn’t thinking of minimalism. Minimalism hadn’t been invented yet. He was thinking of his own sparse and silent fogs of paint. But the point was a salient one, and it held true for the art that came after. Throwing a small pebble into a big lake and watching the ripples radiate is a more fruitful artistic strategy than throwing a boulder into a puddle and standing back from the splash.

In truth, minimalism, which flourished from roughly 1960 to roughly 1970, has not been making any waves in recent times, big or small. It has been one of those parked art movements that we know is there, but that plays no meaningful role in contemporary aesthetics. No one quotes it. No one refers to it.

Instead, aesthetics today is obsessed with identity, gender, historical memory, celebrity, sexuality, political image — chatty subjects in which minimalism was spectacularly uninterested. Social media, a crucial shaping force in contemporary art, does not interest itself in minimalism because it cannot interest itself in minimalism. Minimalism had no points to make or handles to grasp; no accusations to hurl or #MeToos to join. There was only the art object itself: present, simple, actual.

Which is why, reader, this particular camel lapped up the superb minimalism show that has arrived at the Sprüth Magers gallery like a thirsty dromedary that has just crossed the Sahara. What a relief to be enjoying art for the reasons that art is surely meant to be enjoyed: for the colours, the shapes, the visual poetry.

Crossroads: Kauffman, Judd and Morris presents three masters of minimalism, two of whom are well known — Judd and Morris — while the third is not. Not in Britain, at least. In fact, Craig Kauffman’s work has not been presented in London since he appeared in a mixed show at the notorious Robert Fraser Gallery in 1967. Fraser, otherwise known as Groovy Bob, who can be seen handcuffed to Mick Jagger on drugs charges in Richard Hamilton’s archetypal 1960s pop painting Swingeing London 67, was the hippest art dealer in town. His tastes were zesty and urban, and the display at Sprüth Magers does indeed reveal Kauffman’s brand of minimalism to have been lighter and brighter than Judd’s or Morris’s.

One reason for that is that Kauffman (1932-2010) was from Los Angeles, whereas the other two preferred New York. The West Coast/East Coast divide in American art is easy to overstate, but that does not mean it never existed. From the moment you step into this stimulating show in the elegant Mayfair spaces of the Sprüth Magers gallery, it is obvious that Judd’s work is weighty, while Kauffman’s is sprightly; Judd’s colours are profound, but Kauffman’s are uplifting. In pop-music terms, it’s the Velvet Underground v the Beach Boys.

Both artists worked with Plexiglas, a material favoured by minimalists because of its industrial flexibility. Plexiglas did exactly what you told it to do. What is exciting is how different the effects could be.

Judd combines a deep blue Plexiglas with rectangles of galvanised iron in one of his famous Stacks, a minimalist shelving system that climbs the wall in perfect steps. It’s a work that taps into visual memories that are murkily ancient: the steppings of a ziggurat; the Greek system of proportions. There’s a feeling that what is being measured is a design eternal that has always worked. But the killer touch — the feature that stirs — is the blue of the Plexiglas. It’s a Parker ink blue, well on the way to being black, that you also find in the sky at night or the depths of the sea. Reproduced in unblemished industrial Plexiglas, it thrusts your thoughts in surprisingly cosmic directions. This may be hardcore minimalism, but its mood has about it some of the poetry of Van Gogh’s Starry Night.

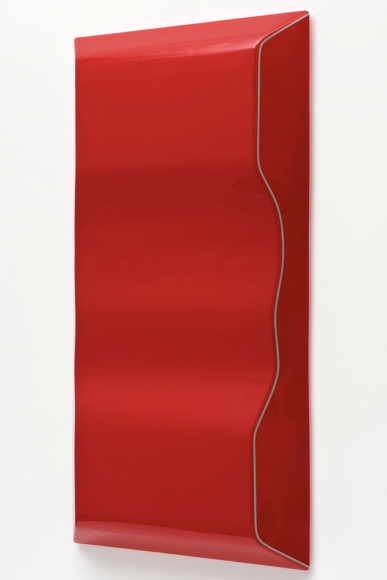

All this is very different from Kauffman’s use of Plexiglas. Where Judd’s colours feel as if they started out somewhere deep in the natural world, Kauffman’s seem to have been found in a bag of sweets bought on Venice Beach. Working with vacuum-formed shapes that are rounded and puffy, Kauffman’s Plexiglas reliefs look like giant jellies stuck to the wall. Unusually for art, they pleasure the mouth as well as the eyes, and struck me as powerfully lickable. You will be pleased to hear that I resisted the temptation to bite into the big orange one hanging opposite the deep blue Judd, but had I done so, it would surely have been tangy and fizzy.

Next to Kauffman’s fizzy orange jelly hangs one of his fluttering hoops, a rectangular sheet of Plexiglas, hand-coloured with vivid greens and tasty pinks, that falls like a curtain in front of the wall. The light shining through throws coloured shadows on the surfaces behind as the solids and the shadows have fun creating stained-glass effects together. When you stand in front of a Kauffman hoop, the delicate fogs of colour stack up in layers like a 3D Rothko.

Upstairs, the cast changes, and so do the moods, as Kauffman is paired with Robert Morris, an altogether grittier minimalist who makes work out of dark grey felt, a material that sags where Plexiglas soars. In one of his pieces, a cascade of felt, cut into strips, tumbles down a wall as if seeking to record the movement of a waterfall. In another, called Fountain, seven strips of grey felt have been carefully stacked into a diagrammatic approximation of spurting water. The result is a stern artwork that will appeal to visiting monks, but that sent me scuttling back to the lighter joys offered by Kauffman, who has saved his best till last with a gorgeous wall relief from his Washboard range.

The Washboards, from 1967, are rolling expanses of vanilla-coloured Plexiglas hanging on the wall like a picture. Think of a mattress of Cornish ice cream shaped into a mountain range. Once again, this is art that stimulates the mouth as well as the eyes. Yum yum. There is something also of the perfect 1960s car body about these rounded and shiny and creamy surfaces.

Collectively, the point made by all this is that there is nothing minimal about minimalism. Colour and shape — the essential building blocks of art — are a bottomless box of Lego that can be taken in a million directions. It’s a beautiful and refreshing lesson with which to begin a new year in art that I hope will be filled with less social history and more optical joy.

I came into art to see things that have not been shown before, not to be lectured by unhappy curators with identity issues or politics degrees or sociology diplomas or chips on their shoulder. Visual art is a “visual” art, and that’s how its messages need to be conveyed, not with cascades of explanatory text.

Crossroads: Kauffman, Judd and Morris, at Sprüth Magers, London W1, until Mar 31