Poor art. In times of conflict, it has been art’s fate to be the football that everybody wants to kick. Goodies, baddies, players, spectators — even the ref, on occasions — have had a swipe when words aren’t enough, and you need the rest of us to notice.

In my lifetime, the single most barbaric act of political football that has taken place involving art was the dynamiting of the Bamiyan Buddhas by the Taliban in Afghanistan in 2001. The beautiful giants had stood on their hillside for a millennium and a half, emitting an aura of transcendental calm and doing no harm to anyone. Yet still the spiteful logic of fanatical Islam found a way to argue for their destruction.

A memory of that grim extirpation popped into my head as I tiptoed through Soul of a Nation, a harsh and choleric event at Tate Modern devoted to the Black Power movement and the art that thundered out from it. It’s not a destructive show. Not at all. But it has moments of real spite in it, and features some artistic attitudes that no one ought to support.

“What is a pig?” asks a savage drawing in The Black Panther magazine of a blind and amputated porker surrounded by flies. “A creature that bites the hand that feeds it,” comes the answer. “A foul, depraved traducer.” A few pictures later, another pig is being throttled and told to “Get out of the ghetto. Get out of Asia. Get out of Africa.” Get out. Get out. Get out. There isn’t actually a sign outside the show saying “Fat middle-aged white men keep away”, butI did intuit quickly that I may not be the target audience.

In truth, the complications commence before you even reach the art, because playing on agenda-setting monitors outside the exhibition door is a selection of speeches delivered by key figures in the Black Power movement; and you could hardly ask for a starker contrast in style and message than the simultaneous presences of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X.

Dr King was centred, foursquare, noble, and his description of his great dream still feels history-changing and rousing. Malcolm X was magnetic but weaselly, a ranting demagogue of the kind who should never be listened to. Having called King a “chump” and a “religious Uncle Tom”, having branded white people as devils and demanded a violent separation between the races, he went on to become a Sunni Muslim and to change his mind about racial difference. We should all get on, he eventually advised. It was too late. In 1965, he was murdered by three of the activists whose violence he had stirred.

So there they are, contrasting starkly at the start of the journey: two ways of winning a fight. The powerful, noble, Martin Luther King way; or the ranting, unstable, mad and murderous way proposed by the useful idiot who was Malcolm X? Stillness or frenzy? In art, as in the world of political mouthpieces, stillness or frenzy is a contrast that counts.

We begin with the Spiral Group, a New York collective of black artists who came together in 1963 to add their voice to the fight for civil rights. They had a single show in which they insisted that all the exhibited work was black and white. Judging by the sample presented here, it was an effective idea that conveyed its stance through the mysterious process of optical osmosis with which art, and only art, communicates.

The best of the Spiral artists, Norman Lewis, shows us a patchwork of flickering whites on a black background that takes a moment to register as a scene of Ku Klux Klansmen rampaging through the night. It’s called America the Beautiful.

I would have liked more of Lewis — indeed, more Spiral art in general. Instead, an impressive length of curatorial paperwork on the opening walls outlines the thinking behind this event and the organisational thrust it follows. What did it mean to be a black artist in the US during the civil-rights movement and at the birth of Black Power? What was art’s purpose and who was its audience? Having asked the questions, the show ahead never feels especially determined to answer them.

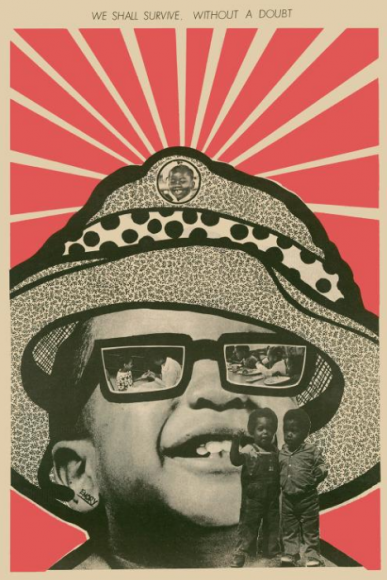

Instead, we get various clusters of artists brought together for assorted reasons, some accidental, some geographic. The AfriCOBRA artists in Chicago created eye-popping psychedelic portraiture in which Malcolm X is presented as a black prince in a pulsing cosmos of lurid colours borrowed from Kool-Aid soft drinks. The section entitled Los Angeles Assemblage gathers a group of LA sculptors who made their work out of scrap metal and quotidian discards. There are big hints of “outsider art” about their efforts, and a strong sense of wanting to operate outside the mainstream. I just wish the art was better.

What is good here is the avoidance of the usual art storylines. We are not watching the spread of pop art or the emergence of minimalism or the coming of postmodernism or any of the familiar plot developments American art is said to have followed. At different speeds, in different places, different groups of black artists are searching for an independent identity.

Alas, too many of them resort too bluntly to the listing of horrors. Archibald Motley packs a dark-blue night scene with Ku Klux Klansmen, skulls, rabid dogs, winged devils, screaming masks, burning crosses and white supremacist placards, a bursting catalogue of sins against the people painted in a stiff surrealist style that makes Paul Delvaux look fluent.

It is not until we get to the cluster entitled Three Graphic Artists that this urge to list slows sufficiently for stillness to triumph over frenzy. Charles White, a veteran of the interwar New Deal arts projects, honed his graphic skills in Mexico with Siqueiros and Rivera. His sepia portraits modelled on the wanted notices put out for runaway slaves in Civil War times are sad, solemn and haunting. White’s pupil in Los Angeles, David Hammons, the most impressive artist in the show, makes “body prints” with his own flesh, in which the accusatory imagery looms momentously out of the gloom.

The photographs of black faces by Roy DeCarava are another high point, and another triumph of extreme stillness. Indeed, photography fares well here, with Dawoud Bey, further along the show, adding a clutch of utterly tangible street characters.

And that’s almost it for the good news. A large gallery filled with abstract paintings argues that black artists could do all the styles, and that the politics of suppression could be purposefully forgotten. Thus William T Williams set out to capture the rhythms of jazz in a lively interweaving of strips and angles. And Virginia Jaramillo paints a beautiful minimalist square of dark forest green, across which skip a pair of pink firefly trails. But just when you believe the argument really has moved forward, a large, black triangular painting by Jack Whitten, called Homage to Malcolm, is described in its caption as a response to a trip to Egypt on which Malcolm X visited the pyramids. Silly.

A gallery devoted to Black Heroes is so unsure of its territory that it includes Andy Warhol’s famous silkscreen portrait of Muhammad Ali. In Brilliantly Endowed, Barkley Hendricks paints himself naked from the hat down, tackle dangling generously, prompted by a review in The New York Times in which the critic Hilton Kramer opined that Hendricks was “a brilliantly endowed painter who erred, perhaps, on the side of slickness”. Cue a painterly double entendre from the Sid James book of profundity.

The nadir is the room devoted to the voodoo assemblages of Betye Saar, inspired by her journeys to Haiti. On her return to LA, Saar began churning out shrine-sculptures fashioned from bones, shells, candles, feathers, dolls: a witch-doctor art copied directly from Haitian examples. Appropriating the magic of another culture is a cultural sin no matter who’s doing the stealing.

Soul of a Nation, Tate Modern, London SE1, until Oct 22