There are different ways to be unknown in art. The most obvious involves working in solitude, so no one hears you or notices you. But you can also be unknown in the full glare of fame. However notable you are, if everyone thinks you are doing one thing, when actually you are doing something else, your artistic intentions remain unknown. This is what Tate Modern is suggesting has happened to Georgia O’Keeffe.

As the best-known woman artist in America, O’Keeffe (1887-1986) never had much difficulty getting noticed. For various reasons — which we’ll come to, as they are a feature of the show — her long career was spent mostly in the spotlight. Indeed, by the time of her passing, she was so much of an American national treasure that her work had acquired an ubiquity many found ghastly. Me included.

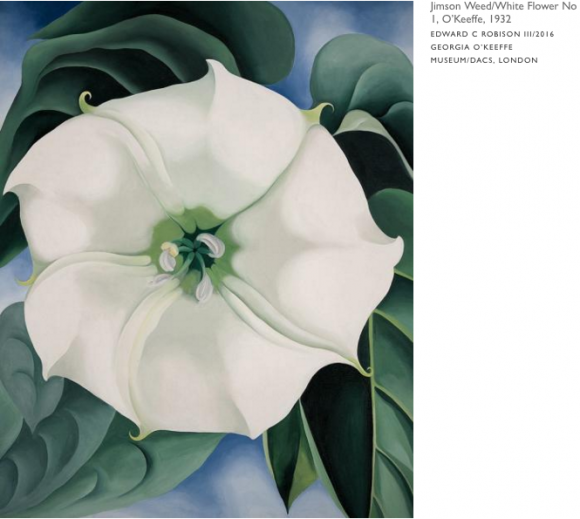

In particular, her flower paintings were familiar. So familiar that they had acquired the aura of very expensive tourist tat. In 2014, one of them, Jimson Weed, from 1932, was sold at Sotheby’s in New York for $44.4m — the highest price paid for a work by a woman artist. It’s in the show. And, like all her flower paintings, it would look fully at home pinned by a magnet to a fridge door.

This is the problematic backcloth against which Tate Modern has set out to examine O’Keeffe’s seven-decade career. It has had to cope with inordinate celebrity, with inordinate misunderstanding, with inordinate familiarity and with inordinate amounts of flower painting. To its enormous credit, it does all this remarkably well, in a show so elegant and thoughtful, we must rank it among Tate Modern’s best.

To come first to the flowers — there are hardly any here. Having set out to paint a radically different picture of O’Keeffe, the exhibition elbows out her bouquets with surprising brusqueness. A single alcove with half a dozen New Mexican blooms in it, including the big white record-breaker, is all that has survived the censorship.

In this new exhibition light, however, even the horticulture appears vital. Along one of the alcove walls, a beautiful set of dark purple irises twist cubistically through the dimensions, so you are not sure if they are flower-sized or sky-sized. Where most flowers in art sit politely in a vase and ask to be admired from a distance, O’Keeffe’s are pushed impolitely into our faces, so we have no choice but to bury our noses in them.

That’s one of her modes. She has many. In the same alcove, a tiny triptych of vegetable still lifes — a pear, some figs, an eggplant, all set against something white — reveals a set of minimalist pictorial ambitions that are as condensed and poetic as a haiku. Small or big, there’s a sense of ecstasy to everything she paints, a pleasure in seeing that communicates itself to us with high excitement. And that, finally, is what the show is about, O’Keeffe’s exciting way of seeing.

Back at the beginning, the display jumps into action with a recreation of her artistic debut in New York in 1916, in an exhibition organised by Alfred Stieglitz, the pioneering modernist photographer whom she went on to marry. Held in Stieglitz’s 291 gallery, this first show consisted mostly of black-and-white drawings in which she explored the foggy border zone that separates abstraction from figuration: it’s what she always did.

Special No 12, from 1916, looks like the uncoiling of a fern, or perhaps the trembling scroll of a cello whose lower half is playing Schubert. A sculpture nearby, called Abstraction, has the same sense of thrusting gently upwards. O’Keeffe explained that she was actually searching for a pictorial representation of “something like a kiss”. But when you deal in pictorial ambiguity, you enfranchise all opinions, and Stieglitz, immersed fully in Freud at the time, understood abstraction as an erect phallus. To make his view unmissable, he placed it next to a dark hole in the clouds that O’Keeffe had also drawn, and which could pass handily for a vagina. Thus was born the sexual understanding of her work that prompted the first spurts of her enormous fame.

Being a woman artist in modernist America was pioneering enough. Being a woman whose work described a sublimated Freudian rutting really got the saliva spouting. O’Keeffe herself argued consistently against these macho understandings, and the present organisers take her side by focusing on the lyrical and floaty nature of her earliest abstractions. What she was really trying to do, the show says, was to find an artistic equivalent of music: to paint pictures that achieve with colours and forms what music achieves with rhythms and melodies.

It’s an argument that is mostly convincing, though I must say the sense of intimate female anatomy emanating from the picture called Grey Lines with Black Blue and Yellow, from 1923, is so tangible that it is no surprise Judy Chicago, the radical feminist artist, based an entire creative campaign of the 1970s around the certainty that O’Keeffe had painted a giant multicoloured vagina. Which is certainly what it looks like.

It’s also clear that Stieglitz’s passion for her had a powerful erotic tang to it. The photographs he took of her naked are the handiwork of a man transfixed by a big, bold, beautiful body. The oversexed O’Keeffe may have been a caricature, but so, surely, is the unsexed one. Happily, the sexual content of her work is always gentle and intimate, never strident and shouty.

This isn’t just a show about her paintings. Her relationship with Stieglitz exposed her as well to modernist developments in photography, and among the exhibition’s many bonuses are the stretches devoted to the work of Stieglitz, Paul Strand and Ansel Adams. All left a mark on O’Keeffe’s painting, from Stieglitz’s billowing views of clouds to Strand’s ambiguous details magnified into dramatic abstraction.

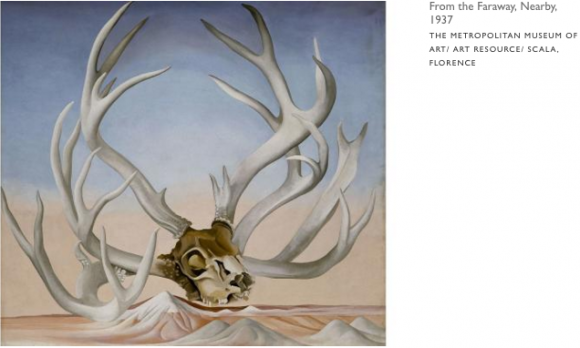

By looking at work produced from 1916 to 1960, the show concentrates on O’Keeffe’s most fertile years and is able to avoid the sense of repetition that affected her final phase: the tourist-tat era. In most instances, the pictures are presented in like-minded clusters — the flowers get an alcove, as do the skulls and the early views of New York — creating a sense of jumping from theme to theme that makes for a lively viewing experience, but is, perhaps, mildly misleading.

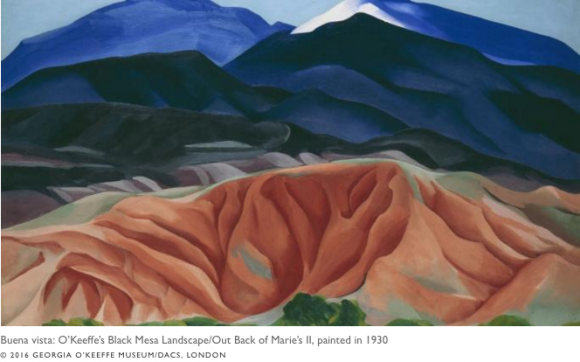

It’s less of an issue after her move to New Mexico, which she first visited in 1929 and which soon became her home. There, everything she needed was viewable from her porch, and the show becomes a tribute to the dry, bony, twisty beauty of the New Mexican landscape.

There’s a charge to every vista she paints, as if the lightning strikes have left their electricity behind in the ground. It isn’t just the skulls of dead steers, picked up in the desert, that exude this air of charged surrealism. The entire landscape seems full of it.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Tate Modern, London SE1, until Oct 30