Hilma af Klint ought to be a household name. When people speak or write of the pioneering moments in modern art, the first steps, they ought to have her near the top of the list. But they don’t. They applaud Kandinsky, Malevich, Delaunay. The better-educated ones even nominate Frantisek Kupka. But nobody mentions Hilma af Klint. At least, they never used to.

Why this is so is made clear by a remarkable show that has loomed up at the Serpentine Gallery. It looms because the spaces are filled with huge pictures of a sort you will not have encountered before — wall-sized enfoldings of girly pinks — but also because it asks towering questions of art history. The unveiling of Hilma af Klint is more than a correction to the story we were taught at school. This is a whole chapter torn out of the book, crumpled into a ball and kicked into the bin.

Although this is the most ambitious selection of her work to reach Britain, her actual unveiling can be backdated to 1986, when an event called The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985 opened at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. It included 16 of her works and was one of those rare shows that rewrite things. But not everyone took its revelations seriously. Especially not the self-appointed arbiters on matters of 20th-century progressiveness — the snobs who run the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Having come up with the narrative of modernity that is habitually passed down to us, MoMa wasn’t about to be challenged by a crazy Swedish occultist nobody had heard of and whose work was employed in a madcap search for thes-word. MoMA doesn’t do spiritual. And it certainly wasn’t going to be lectured on the subject by a bunch of West Coast hippies from Scientology Town with a taste for new-age psychedelics. I exaggerate. But those were the dynamics of the situation.

Born in 1862, Hilma af Klint was the daughter of a Swedish admiral who, with excellent Swedish freedom of thought, encouraged her to study art in Stockholm in the 1880s. Her training was conventional. But somewhere along the line, she encountered the esoteric doctrine of theosophy and fell for its ceaseless confusions. She thus joins the impressive roster of artists — Gauguin, Pollock, Mondrian, Malevich, Kandinsky — whose work was transformed by the pseudoreligious ramblings of Madame Blavatsky. Theosophy was nonsense, but it was a nonsense that liberated the imagination and made you paint things that had never been painted before. Its big gift to art was the notion that differences are unimportant, because underlying them all is a bigger and better cosmic order. And that’s what af Klint was trying to paint.

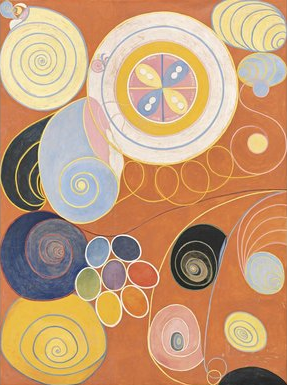

I can’t remember the last time I walked into a show as original and as, yes, weird as this one. The strange pictures collected for us by the Serpentine are unlike anything you will have seen before. This is art from another planet. And just look at the dates. That huge pink painting with the blue spirals cascading down it and the whirling yellow windmills in the corner was done in 1907. In a blind test, I would have placed it in the 1990s.

The year 1907 was also the one in which Picasso was said to have invented the first modern ism, cubism, by painting the revolutionary Demoiselles d’Avignon. But in terms of pictorial progressiveness, af Klint’s towering pink abstracts, gathered in a circle of blink-inducing colour in the Serpentine’s central space, make the Demoiselles d’Avignon look like something Picasso might have given to his granny. In the next room, a series of sparse circles and targets from 1914 — with gorgeous colour schemes of trademark pink, pastel blue, shocking yellow — are the best pictures here. When reason leaves its post at the gates of the imagination, and the gates swing open, extraordinary things come conga-ing out.

It wasn’t just theosophy that freed af Klint’s hand. In 1886, she joined four like-minded women artists in a group called the Five, who jointly worshipped a ring of deities known as the High Masters. The Five held séances together and — 30 years before the surrealists — produced automatic drawings for which they held the pencils while the High Masters supplied the directions. It’s bonkers stuff. But it differs not a jot from the imaginings of, say, Fra Angelico, the exquisite painter of Renaissance madonnas, who never altered his art because God had painted it, not him.

The Serpentine’s show is centred on a body of work that af Klint began in 1906 called the Paintings for the Temple. It was intended for a new temple the Five were hoping to build to Amaliel, one of the High Masters. The temple was to take the form of a giant spiral — a theosophical Guggenheim — whose walls were to be lined with af Klint’s remarkable images. Or, rather, Amaliel’s images, which she was painting for him.

The Serpentine’s central space has always had something of the temple about it, and the suite of huge paintings from 1907 that now fills it with spirals, flower patterns, bulging seed pods, suns that become moons, moons that become suns, unknowable diagrams and mysterious mystic scrawlings can never have had a better location. Done on paper, The Ten Largest, as the suite is called, is so lofty that af Klint needed to make the pictures on the floor, prowling their perimeter, Pollock-style. Their new-age imagery is unarguably wacky, but there’s a freshness and a beauty to it, too, that’s unique.

Elsewhere in the show, Amaliel is worshipped in a sequence of square paintings called The Swan, in whichaf Klint switches dizzily from swans you can just about recognise by their outlines to entirely abstract evocations of their binary spirit, recorded in circles and targets. Even the way she slips effortlessly from figuration to abstraction is revolutionary. None of the old art-historical divides — the MoMA divides — slows her down or limits her.

Like much that is here, the trilogy of big pictures called Altarpiece that greets you with coloured pyramids and golden suns is guilty of a preternatural new-ageism that will make some visitors queasy. I haven’t been inside the Scientology HQ, but I fear it must feel a bit like this. And it isn’t only abstraction that is being invented here. The cute pinks and flowing girly script of The Ten Largest are the aesthetics of Hello Kitty, arriving on Earth a century early.

Af Klint died in 1944, and in her will she specified that her art was not to go on show until 20 years after her death. Before then, she foresaw, the world would not be ready for it. She was right. In fact, this strange mix of beautiful abstraction and dotty symbolism is so out there that the time when it feels commonplace may never arrive.

Hilma af Klint: Painting the Unseen, Serpentine Gallery, London W2, until May 15