It’s been a big week for Manchester in contemporary art. This is unusual. Manchester is renowned for many things, but contemporary art isn’t one of them. While most of the great metropolises of Britain — Liverpool, Glasgow, Newcastle, Cardiff, Nottingham — realised long ago that art has the power to turn nowhere into somewhere, and that this power can be harnessed to achieve remarkable transformations, Manchester has lagged behind. In my spell as a critic, the city has produced nothing of note. No great artists. No great shows. No great movements.

I should add that this failure to engage properly with contemporary art has personal meaning for me. Manchester is where I studied the history of art. It’s where I got my first chance as an art critic. And where I first realised that as far as most folk in Lancashire were concerned, contemporary art was a con being perpetrated on a gullible public by them idiots in the south. The miserable shadow of LS Lowry has loomed over the city ever since, muttering darkly about modern roobish and advising the council to have nowt to do with it.

It is, therefore, with a sense of relief that I can officially declare those days over. After all the decades of stubborn canalside resistance, Manchester has finally become an art town again. At the start of this month, the newly refurbished Whitworth Art Gallery was officially named Britain’s Museum of the Year. And this past fortnight has seen the city’s very own biennale — the Manchester International Festival — sending bright and plentiful sparks into Britain’s artistic cosmos.

In my day, the Whitworth Art Gallery was attached firmly to the university. From the outside, it looked as bricked up and impenetrable as a Victorian boarding school. The interior, meanwhile, offered a building-wide celebration of beige, with hessian walls and low ceilings, oat-coloured matting and camel-tone carpets. It boasted not a single iota of drama and felt more like a bedsit than an art gallery.

A three-year rebuild has put paid to all that. The reconditioned Whitworth that has emerged from the clean-out isn’t merely a new building, it’s a new mood. True, the front has barely changed and still looks implacably bricky. But at the back, the gallery has been extended deep into the gardens with an exciting thrust of glass and openness. Bigger, brighter, taller, immeasurably more dramatic: these are spaces in which art can now be felt as well as studied.

I also enjoyed the higgledy-pigglediness of the layout. It makes finding things an adventure. Asked to draw a map of the route you need to follow to see all the displays available in the Whitworth’s busy opening hang, I doubt many visitors would get much past the entrance hall. This emphasis on audience adventure finds a natural ally in the Manchester International Festival, a biennale devoted specifically to the commissioning of new works and the blurring of the divides between different art forms.

The Whitworth is hosting one of the festival’s blue-ribbon events, a collaboration between two of the grandest grandmasters of the arts, Gerhard Richter and Arvo Pärt. Richter is in many people’s eyes the greatest living artist. Pärt is in many people’s eyes the greatest contemporary composer. On paper, the union ought to work magnificently.

Richter was born in Germany just before the Second World War, and Pärt in Estonia, so they are also highly compatible in mood. Both their young lives were stained immovably with loss, fate, sadness and memory. Two great tragedians. Two great art forms. One new collaboration. It has to work, no?

No. Pärt gets his bit right, with an exquisite choral cycle based on a few sad lines from the Psalms about the truth that comes “out of the mouths of babes and sucklings”, sung in the gallery by an invisible choir scattered among the gallery-goers. That isn’t another visitor standing next to you in the room. That’s a singer whose unexpected Hallelujahs are about to float mysteriously into the air. It’s a gallery trick borrowed very obviously from Tino Sehgal, but it works well.

The disappointment is Richter, whose contribution looks phoned in. On one set of walls, he has arranged a sequence of minimalist grey rectangles, created with mirrored enamels that reflect the action in the room. On the other side, a set of photographs of the concentration camp at Birkenau have been turned into paintings, which were then turned into abstracts, which have finally been photographed again. The results look like the fuzz you get on TV screens when the picture fails.

Conceptually, this complex mix of eradications may well add up to a telling set of losses. Visually, it does nothing much. Where Pärt’s music affects the room immediately, Richter’s deliberate facelessness has almost no visceral impact. And by the time you’ve finished understanding it, Pärt’s part has come and gone.

Elsewhere at the Whitworth, a handy survey of Chinese art from the 1970s until today has been lent by the pioneering Swiss collector Uli Sigg, who donated an extraction of his collection to the M+ museum, due to complete in 2018 in Hong Kong. The four decades under consideration here were certainly tumultuous. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that they witnessed the most rapid transformation ever seen in Chinese art.

The helter-skelter ride begins with a generation of artists who were trained in communist schools to be realistic and loyal, but who turned into madly grinning satirists the moment the freedom button was pressed. Has anyone ever painted a less sane set of grins than the ones exploding out of the face of Geng Jianyi in 1987?

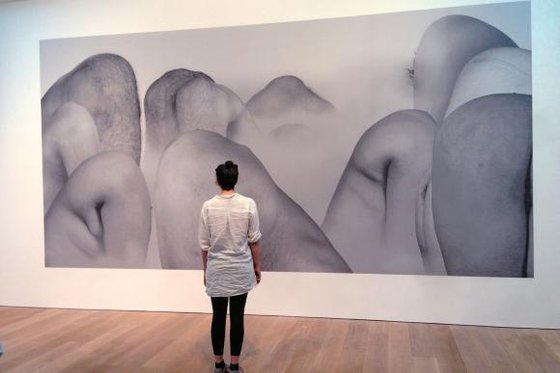

Modern China’s relationship with the past is a recurring theme. Ai Weiwei gives us a selection of 4,000 axe heads, dating back to 6,000BC, laid out carefully on the gallery floor in a work that feels immediately as if it is lamenting the eradication of history. The cleverest work in the show is Liu Wei’s giant mountainscape covered with fog, which looks at first sight like a traditional Chinese landscape, but turns out to show a row of bent-over nudes sticking out their bottoms. No, madam, that thick black clump emerging between the two hills is not a tangle of trees.

In my days at the Whitworth, the gallery was known principally for its collection of English watercolours — works by Blake, Turner, Girtin and Cozens. These have been shortchanged in the opening display, crammed together, row upon row, in what the gallery hopefully describes as “a salon hang”. Basically, you can’t see any of them properly. To view the top row, you need to be 15ft tall.

I hope the new Whitworth doesn’t repeat the mistakes of Tate Britain and become so enamoured of contemporary art that it loses sights of its scholarly responsibilities to the art of the past. Indeed, the Whitworth’s newly ennobled director, Maria Balshaw, who got a CBE in the most recent honours list, is one of the names whispered most often as the hunt gathers momentum for a new director of Tate Britain. Personally, I suspect she has bigger fish to fry.

When Nick Serota, the Tate Obergruppenführer, retires next year— as he surely will after the opening of Tate Modern’s final extension — Balshaw, who has shown herself to be a dab hand at fundraising as well as a superb gallery strategist, will surely be the leading contender to succeed him. She’ll certainly get my vote.

But these are distractions for the future. The big truth now is that Manchester has finally caught up.