How do you paint a war? You would have thought that by 1914 art would have known the answer. Look how much practice it had had. Ever since Homo erectus smudged his first handprint on a cave wall, the waging of wars had been a consistently popular human activity. And whether it was Trajan defeating the Dacians on that big column in the middle of Rome, or Napoleon crossing the Alps in the Palace of Versailles, art was around to applaud the moment.

But what if applause is not what’s called for? What if the war in question is so inglorious and murderous that none of the previous examples help? What if art’s task this time is not to record or glorify war, but to evoke and lament a new version of it?

As the Imperial War Museum prepares, finally, to do its bit in the centenary commemoration of the First World War with the largest display of war art seen in Britain for a century, the clearest point made by the pictures in its Truth and Memory exhibition is that there was no pattern to follow. A different type of war had broken out. It was bloodier, more mechanised, more lethal than any war before it. And to record it, art needed to do a lot of inventing.

The museum has only now joined in with the centenary commemorations because, for the past 18 months, it has been closed for a floor-to-ceiling renovation. Talk about bad timing. The gods of war are never going to be helpful in their watch-keeping, but to call in the builders at the nation’s chief site of commemoration for the best part of the past year really is divine wickedness. Instead, we have heard from Jeremy Paxman. From Ian Hislop. From shelf-loads of amateur Somme historians. From the National Portrait Gallery. From the BBC. And, lest we forget, from our secretary of state for education, Michael Gove, who kicked off the year by complaining about the “Blackadder myths” that were being peddled about the conflict by badly informed Cambridge professors. Everyone, it seems, has had their say about the war, except the institution founded in 1917 to memorialise it. If the topic wasn’t this topic, you’d have to laugh.

Another way of looking at it is to see this Blackadderish timing as typical of the territory. Chaos was the First World War’s defining condition; muddling through, its usual form of progress. How do we know that? Because the art tells us so. The First World War spawned more art than any previous battleground. And much of that art was created by the men in the trenches.

The briefest look into the ghastly field hospital in Dunkirk, drawn for us in 1916 by CRW Nevinson, tells you all you need to know about the conditions endured by injured troops. A young modernist, Nevinson was among those shipped out to France in 1914. He worked at the hospital as an orderly for the Red Cross. His father was a war correspondent and his mother a suffragette, so he knew, better than most, what governments get up to in times of stress. Among the inmates, he later recalled, the Dunkirk hospital was nicknamed “the Shambles”.

The fact that the Imperial War Museum exists at all is itself a triumph of chaotic muddling through. As you stride up to this commanding palace of war in south London, with its two 100-ton guns outside — salvaged from a pair of British battleships — pointing at you, it is worth remembering that the museum is located here by accident. No one was sure where to place it, or what to do with the art that might go in it.

The original idea was to build a new museum commemorating the war in Whitehall, but that proved too expensive. The art was initially put on show in the Crystal Palace, in Sydenham, where the glass walls proved thunderously inappropriate for the showing of pictures.

Next, they took it to South Kensington, to galleries adjoining the Imperial Institute, which stood where Imperial College stands now. Finally, after a further decade of muddling, the Imperial War Museum and its great collection of First World War art was installed in its present home, in the building that used to house the most notorious madhouse in the world, Bethlem Royal Hospital — “Bedlam”.

Having made an appointment to preview the art in the upcoming show, I needed to circle the former Bedlam a couple of times before I found the secret door that gets you in. When you have been inside as many museums as I have, the chaos of the out-of-view spaces does not surprise you. What surprised me here was the chaos of the in-view spaces. With just a few days to go before the official reopening, can these huge expanses of polythene and dust complete their transformation into the Imperial War Museum in time?

My guide, Richard Slocombe, senior curator at the Imperial War Museum, assures me that it’ll be all right on the night. He’s a calm chap, and it would be churlish to doubt him. But I cross my fingers anyway, and keep them crossed all the way round the fascinating loop on which he takes me.

Sometimes the lights work, sometimes they don’t. So we borrow some portable halogens from the builders. But the story that unfolds before us — the story of how British art responded to the First World War — is so darkly compelling that it grips in any light.

There was no original plan to make war art. But with every man in Britain who was vaguely able-bodied being conscripted from March 1916, there were, inevitably, artists among the soldiers sent to the trenches. And it is the eyewitness nature of their work that makes it different. For the first time in art we were viewing evidence from the front line.

The show devotes its opening rooms to Nevinson, who later remembered that the field hospital in Dunkirk smelt of “gangrene, urine and French cigarettes”. What he saw at the front burnt itself into his memory and jolted all his certainties. When his health failed, he was sent back to England, where he set about producing some of the most vivid and searing war art ever made.

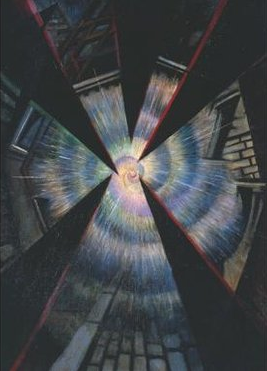

Before the war, Nevinson had studied at the Slade School of Art, in London, and had fallen in with the Vorticists, a gang of noisy British modernists who were championing an aggressively angular and pointy style of painting. Vorticists used rulers instead of compasses. It was a particularly appropriate style with which to record the savage, mechanised dynamics of the new war.

For Slocombe, Nevinson’s 1915 painting, Bursting Shell — a pulsing, driving jet of jagged lines and nuclear colours — is the first true evocation in art of the physical sensation of explosion. Prior to the arrival of Vorticism, there simply wasn’t a style in art that could convey the airborne violence of a bursting shell.

Paul Nash, a Slade School contemporary of Nevinson’s, also found himself on the Western Front. Having initially enlisted as a private for home service in the Artists’ Rifles, Nash retrained and ended up as a Second Lieutenant in the Hampshire Regiment, arriving at the front in 1917.

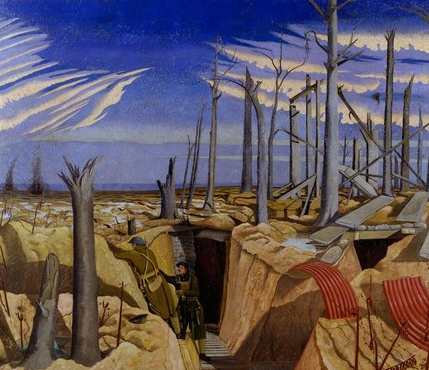

He admitted later to not being much good at figures; he preferred to let the landscape do the talking. And his views of the barren and devastated fields around Ypres and Passchendaele — broken trees rising out of the mud like burnt-out matches — are perhaps the most haunting landscapes in British art. Killing the people is one thing; killing the land is another. The spectacularly desolate primeval quagmire he painted in 1918 (the one he entitled, so Blackadderishly, We Are Making a New World) shows us what happens to justice, hope and patriotism once chaos, absurdity and tragedy have had their say. “I am no longer an artist interested and curious,” he wrote to his wife, in November 1917. “I am a messenger who will bring back word from the men who are fighting to those who want the war to go on for ever. Feeble, inarticulate, will be my message, but it will have a bitter truth, and may it burn their lousy souls.”

Nash’s brother, John, also served in the Artists’ Rifles. In his painting Oppy Wood he depicts two soldiers in the trenches gazing out at what’s left of nature once the war has trampled across it.

In 1917, after an initiative originally taken by John Buchan, author of The Thirty-Nine Steps, who had previously worked in the War Propaganda Bureau, the British government set up the War Memorials Committee. Its job was to allot the task of documenting the war to an officially selected battalion of artists, with Nevinson and Nash among them.

From the stories that Slocombe tells about the committee and their associates in the Censor’s Office, it’s clear that it wasn’t set up just to encourage artists. As their paymaster, it hoped also to control them.

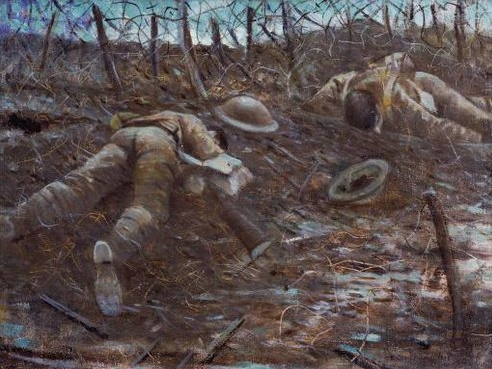

In 1917, when Nevinson painted one of the most controversial pictures of the war, a gruesome view of two dead soldiers lying face down in the mud, which he sarcastically entitled Paths of Glory (a lament borrowed from Thomas Gray’s Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard: “The paths of glory lead but to the grave”), the official censor for paintings and drawings in France, Lieutenant-Colonel AN Lee, refused to let him exhibit it, as showing dead bodies would “hinder the war effort”.

Nevinson would later show the painting in his one-man exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in 1918, but with a strip of brown paper across the offending dead bodies with the word “Censored” written on it.

Unfortunately, use of the word “censored” was also banned. So the Imperial War Museum bought the picture and put it in storage, removing it from sight. Nothing Blackadderish about that, then.

Paintings such as Nevinson’s clumsy, lumpen A Group of Soldiers, also from 1917, showing a gang of glum squaddies in trench coats — “British working man in khaki”, as the artist saw it — were deemed guilty of ignoring the glory of our military achievement. These ugly troops, thundered the censor, would be seen by the Germans “as evidence of British degeneration”. The Saturday Review chimed in with the opinion that Nevinson’s canvas showed “a crew of dummy hooligans”. It prompted an immediate riposte from a serving soldier, who wrote: “Show it to any fellow who has inhabited a dugout … You will hear ‘Good Heavens! He has got home there right enough’.”

All this I learn from my guide, who seems to have no whitewashing ambitions of his own. Richard Slocombe has divided the exhibition into two halves: Truth and Memory. The first seeks to show us what really happened in the war, as witnessed by the artists; the second foregrounds the official attempts to memorialise the conflict. As he shows me round, it isn’t always easy to tell the two approaches apart. To me, it looks like the war gatecrashed your vision violently, whoever you were.

William Orpen was already a successful society portraitist when he was made a war artist in 1917. Admitted into the Dublin School of Art at the ridiculous age of 11, Orpen was so gifted that he had built himself a career from painting and knowing the well-to-do while still a teenager. Because of his connections he entered the army as a Major, and fetched up in France expecting to glorify the allied effort. But, as the extraordinary room devoted to him makes clear, that is not what happened.

According to Slocombe, Orpen had some sort of epiphany at the Somme. His art, having been smooth and effortless until now, suddenly became strange and twisted. In an eerie view of two dead Germans, slumped like discarded puppets in a trench, the glowing blue of the sky and the whiteness of what you assume must be the surrounding snow create an absurdly pretty impressionist colour scheme. Only when you read Orpen’s explanation do these weird colours begin to make sense: “The dreary dismal mud was baked white and pure — dazzling white … The sky was a pure dark blue, and the whole air… thick with white butterflies. It was like an enchanted land; but in place of fairies there were thousands of white crosses, marked ‘Unknown British Soldier’.”

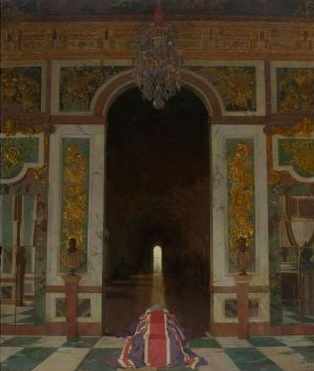

Orpen was later dispatched to Versailles, to record the negotiations for a postwar peace. So appalled was he by the machinations of the vainglorious and self-serving politicians gathered in the famous Hall of Mirrors that he parodied the occasion and its setting in the painting entitled To the Unknown British Soldier in France. It shows a simple coffin draped in a union flag, framed by a plush doorway in Versailles. Originally, the coffin was attended by the wretched ghosts of a pair of Tommies, but the War Office didn’t approve of their presence and Orpen painted out the apparitions, creating a pictorial accusation of even starker simplicity.

A few years later, he gave most of his war art, 138 pictures in all, to the Imperial War Museum, on the understanding that it would always be kept and shown together.

The last time this many perspectives on the conflict were put on display together was at the Royal Academy, in 1919. One newspaper headline of the day complained loudly of the “Bolshevism in art”. Another shouted: “Heroes made to look like clowns.” A critic for the Daily Mirror said he now knew what was meant by “the horrors of war”, adding “it’s the pictures”.

One of the targets of press outrage was a painting of a British gun battery being shelled by the Germans, by the former leader of the Vorticists, Percy Wyndham Lewis. Having served on the Western Front as a Second Lieutenant in the Royal Artillery, Lewis had witnessed a mechanised death raining down on a degraded humanity: the sudden lethal explosions; the soldiers scurrying underground. All this he recorded with a Vorticist spikiness that seems somehow to have a smirk on its lips.

No one knows for certain who the three figures are in the foreground of Lewis’s A Battery Shelled — the ones who seem to be greeting the exploding shells with such surprising nonchalance. To me, they have the look of the officer class about them. So embarrassed was the museum by the painting that it sent it out on long-term loan to the Tate, in the hope that it would pass for a piece of modernism. And not war art.

Thus these pictures of the First World War tell a story that is fascinating, exciting and inglorious. Thank heavens the Imperial War Museum has arrived on the scene in the nick of time to tell it.

The generals and the propaganda chiefs would have us believe that muddling through is no way to fight a war. But the museum probably deserves a medal for making so clear that sometimes muddling through is the only path to glory.

Truth and Memory: British Art of the First World War is at the Imperial War Museum, London, from July 19