As China’s most celebrated dissident artist, Ai Weiwei has had to cope with appalling things. They put him in prison. They took away his passport. They put a ring of surveillance cameras around his studio and never turn them off. To have made art as good as Ai Weiwei’s in these grotesque circumstances is a remarkable achievement.

Yet, perversely, he can also count himself artistically fortunate. More artistically fortunate, I would say, than those happy hipsters you see wandering in and out of Chelsea School of Art when the fancy takes them. For the Chelsea hipsters, all the freedom in the world is a hindrance, not a help. Their fundamental problem is that they have nothing to make art about.

God: What have you done in life?

Student: I’ve been an art student.

God: What’s your new piece about?

Student: Well, er, I thought I might make a video work examining issues of desire in Lara Croft.

God: Oh.

No such pointlessness has been possible for Ai Weiwei. The circumstances that ruined his life have been the making of him as an artist. One thing he has never had to struggle with in his output is a sense of direction: an awareness of his creative task. His art is about his life, his land, his predicament and that of his countrymen. The toughest part of art-making — finding your subject matter — has been a given.

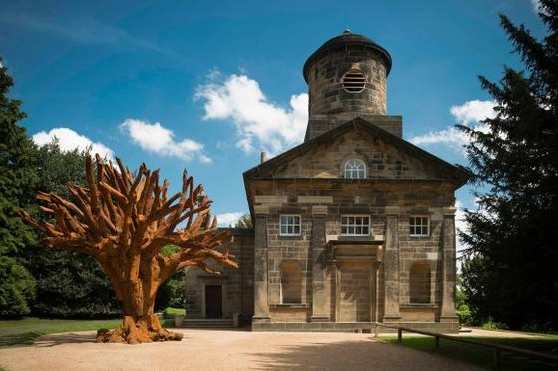

I thought about all this in the perfect thinking space that is the new Chapel gallery at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, where a selection of Ai Weiwei pieces created specially for this event has been unveiled. Built in 1744 from austere blocks of Georgian sandstone, the Chapel had the original purpose of providing a simple place of worship for the inhabitants of the surrounding Bretton estate. Now, after a £500,000 restoration, it has been opened as an exhibition space, with Ai Weiwei as the first exhibitor.

I mean it as no slight on him when I tell you the journey to see this opening display is worth making for the new gallery alone. These fine puritan spaces, with their resonant sparseness and lovely minimalist coloration of light striped with dark, have a contemplative power all of their own. Add Ai Weiwei to the mix, and you have a truly magical artistic moment.

With his passport taken away, Ai Weiwei could not travel to Yorkshire to install the show or familiarise himself beforehand with its location. All he had was some photographs and a set of dimensions. So the fact that it all looks so right, so measured and purposeful, tells us something important about his artistic intelligence. “Conceptual art” has become a well-nigh meaningless phrase, but Ai Weiwei’s ability to foresee and ensure a poetic confrontation between his art and his visitor is conceptualisation of a particularly brilliant variety.

Outside the Chapel, in the clearing at the front, he has placed a huge metal tree: a blasted oak, created out of hefty logs of iron cast from real branches, then bolted together, so their textures and outline feel immensely real. Six metres tall, leafless and looming, it’s a very powerful sight.

Although it feels like a blasted oak, it is actually a Frankenstein tree, assembled from different bits of many species. Apparently, street vendors in southern China sell ingenious wooden trees made in this way. But trees mean something important to every nation on earth, and the metal bole immediately triggers all kinds of plangent arboreal memories. It reminded me of those gnarled single oaks you find in the middle of Rembrandt etchings, standing in for the condition of man. Or the tall pines on the tops of hills that allude to the Crucifixion in the altarpieces of Caspar David Friedrich.

Its rusty iron surfaces, meanwhile, seem to expand the artistic conversation quickly to issues of ecology and the despoliation of the natural world. Placed perfectly outside a Yorkshire chapel, the metal tree has such a rich and insistent symbolic presence. Amazingly, it even manages to look completely at home, like one of those charming midsummer yews you see planted, so innocently, in a typical English churchyard.

Inside the Chapel, Ai Weiwei’s vigorously opportunist sense of place finds an even better location. It is many decades since anyone visited the Chapel at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park for religious reasons, but these kinds of stripped-down, puritan spaces never fully lose their air of sanctity: bare white walls, hard dark wood, a minimalist feel of discarded decoration. These are spaces that cut to the religious quick.

In this instance, instead of the expected lines of neat pews, we find an unexpected arrangement of antique Chinese chairs, 45 of them, all different, all dating from the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), arranged in rows, nine of them, five chairs per row. At first sight, the rows of chairs seem very ordered and neat: to form a united presence, like a marching army, or a singing choir. But you quickly realise that each one is, in fact, different: sometimes subtly so, sometimes obviously. What seems to be a united mass is actually a push-and-pull tussle for individuality. Thus the chairs are stand-ins for the individuals in the crowd, and, most specifically, for the Chinese individual in the Chinese crowd.

Ai Weiwei is certainly not the first artist to note the symbolic impact of an empty chair. When Luke Fildes painted his famous Victorian image of Dickens’s empty chair, he threw a hefty pebble in the pond. Van Gogh, a lover of Fildes’s pictures during his time in England, responded with his own empty chair, followed by Gauguin’s empty chair. Because empty chairs resonate powerfully with the presence of their missing owners.

With Ai Weiwei’s chairs, there is the extra joy that they are so beautifully made, in precise displays of ancient Chinese woodworking skills: skills that, you instinctively understand, have been lost to the world. As so often happens with Ai Weiwei’s work, a political meaning blurs quickly into a nostalgic one.

This, then, is an iceberg of a show in which the things you see conceal huge amounts of hidden meaning. And there’s more. If you turn up at the Chapel at the right times, you can also hear poetry readings from the work of Ai Qing, Ai Weiwei’s father, a famed revolutionary poet whose journey took him from the side of Mao Tse-tung to exile in a Chinese labour camp that lasted until Mao’s death. Reading his poems in the chapel, I was struck by how close the son’s way of thinking was to the father’s:

Trees

One tree, another tree,

Each standing alone and erect… But beneath the cover of earth

Their roots reach out

And at depths that cannot be seen

The roots of the trees intertwine.

Ai Weiwei, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield, until November 2