Children, if you stopped on this page because of the big cartoons and you thought this must be the Funday Times, trust me, it isn’t. This article is about grown-up stuff. Stuff that mummy and daddy do. A lot. So if you’re under 18, stop reading now and hand this magazine back to them. Off you go. No peeking. Actually, if you’re any age under 35, it’s probably best to flick to the next article. I doubt your mum and dad will want you reading about shunga, just yet.

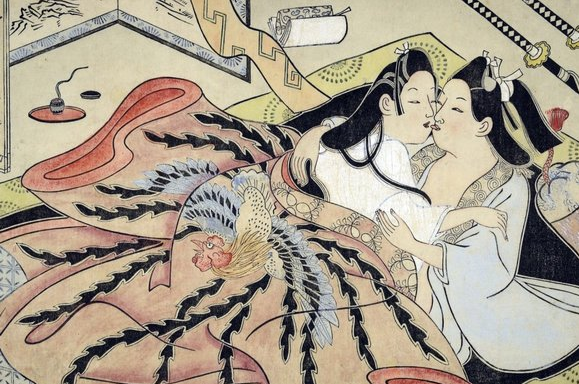

So, over-35s, it’s me and you! What have we got here? What is shunga? And why am I writing about it now? The first thing to clear up is the difference between shunga and bunga bunga. Yes, they both sound foreign and naughty, but bunga bunga is a specifically Italian form of naughtiness involving corrupt prime ministers and young girls called Ruby, while shunga is specifically Japanese and involves everyone, everywhere. Another big difference is that bunga bunga is sordid, while shunga is not. A uniquely Japanese form of erotic art, featuring some of the most inventive intertwining ever attempted by two, three or four people — they don’t even have to be people; octopuses can get involved as well — shunga has recently been the subject of much scholarly enquiry, and is, these days, considered to be a mightily important cultural topic. So un-sordid is it that the British Museum is about to open a big exhibition celebrating its history and presenting shunga as great art. Under-16s will need to be accompanied by an adult. Personally, I’d be more concerned about the over-75s. Perhaps they could list the numbers of some handy cardiac specialists in the catalogue.

Anyway, we will soon be needing to deal with shunga in an adult fashion, so I thought it a good idea to confront this prickly subject early with a spot of pre-emptive penetration. Sorry, maybe penetration isn’t the right word. We’re going to come at this from a different angle. What I mean is we’re just going to dive in.

Shunga originated in Japan around the 10th century. The word means “pictures of spring” in Japanese, although spring in this context appears to involve an oriental double entendre relating to conjugal behaviour. The first shunga-like images were inspired by Chinese medical books, and in particular the sex guides given to emperors to teach them the positions in which yin could be connected fully with yang. As the Maiden explains to the Yellow Emperor in an important Chinese text called the Koso Myoron, which was translated into Japanese in about 1536: “Yin–yang intercourse between heaven and earth brings into being all things in the universe. The lack of yin–yang relations between a man and a woman results in ruin.” In short, the more shunga, the better.

Although its origins are ancient, shunga’s heyday was the Edo period, between 1603 and 1868, when Japan cut itself off from the rest of the world with a series of remarkable laws designed to separate it from us. The Closed Country Edict of 1635 forbade Japanese nationals from travelling abroad, or from returning if they managed somehow to leave. All foreigners were banned from visiting Japan, except for a small number of Dutch traders allowed access to the tiny island of Dejima in Nagasaki harbour, which wasn’t considered to be Japanese soil because the island had been created artificially by advanced Japanese engineering. Any foreigners who arrived elsewhere in Japan were executed without trial.

This is the extraordinary epoch on which the British Museum show will focus.

Separated from the rest of the world for 2½ centuries, encircled by water, unwilling to interact with anywhere else, Edo-period Japan developed a unique cultural ecosystem in which shunga grew and thrived. It’s a bit like Galapagos tortoises, related to tortoises everywhere but enlarged by unique circumstances into a spectacular endemic form.

When I say spectacular, I mean spectacular. Enlarged forms do not grow much more enlarged than the huge oriental todgers that get waved around in shunga. Those of us who have imagined the Japanese to be lightly built in the lunchbox department will need to begin re-imagining furiously after this display. What is being described here in these busy scenes of round-the-clock fornication is a nation of well-endowed studs who appear, on this evidence, to spend all their waking hours ensuring that the yin-yang equilibrium is fully maintained. To make sure that we spot the member in all the furious intertwining that characterises shunga, the artists of the Edo period even added helpful bits of colour-coding to their imagery. See that dark tree trunk being sucked helplessly into the centre of that swirling red whirlpool? That’s not a tree trunk. And that’s not a whirlpool.

The British Museum will be including various ancient fertility objects in its display to remind us of the sheer oldness of this territory: portable wooden penises and the like, which we used to carry around and worship in our untrousered past. There are some erotic netsuke too, Japanese belt toggles made of ivory, which open up to reveal energetic couples busily maintaining the yin-yang equilibrium. The bigger point the show will seek to make is that, for most of human history, sex has been a central subject for art — the force that makes the world go round — and it is only in our own deviant times that this ancient linkage between human existence and art has been broken. No arguments there. You only have to look at the cover of Nuts magazine to see how deviant we have become.

Interestingly, most of the more curious exhibits on show were originally deposited within something called the Secretum. Did you know the British Museum had a Secretum? Me neither. It seems that as long ago as 1865, a keen British collector of erotica called George Witt, a former mayor of Bedford, physician and banker, donated his collection to the British Museum where it was hastily shoved under the mattress and kept from public view for the best part of a century. So secret was the Secretum that only trusted BM curators were allowed access to it. Nowadays, its contents have been divided up among the various cultural territories from whence they were plucked, but it remains true that the British Museum has kept all this very quiet for a very long time.

Timothy Clark, the head of the Japanese department at the British Museum and the curator responsible for Shunga: sex and pleasure in Japanese art, occupies a secretum of his own hidden away behind a couple of doorways at the far end of the Japanese section. Neat and bespectacled, Clark displays no outward sign of being passionate about the orient; whatever it is that fascinates him about shunga is kept out of sight beneath a dusty academic exterior — this is a man who clearly ranks the pursuit of knowledge above all the rest of life’s myriad pleasures. Somewhere inside, shunga must have given his Englishness a furious shaking.