It’s appropriate that an investigation of Picasso’s relationship with British art should arrive in Diamond Jubilee year, because Picasso had a lot in common with diamonds. He sparkled. He cost plenty. Girls liked him. His most diamond-like quality, however, was an ability to appear different from every angle. Whichever way you turn him, he always presents another facet. That is why bad Picasso exhibitions are so difficult to achieve, and why even a show as unpromising-sounding as Picasso and Modern British Art manages to end up as a thrilling event.

The show was unpromising because it is one of a pack of jingoistic openings this year that owe their arrival to the Olympics. With the eyes of the world upon us, our galleries have simultaneously developed a shared propagandist ambition. Did somebody send a memo? Is that why Hockney has arrived at the Royal Academy, Freud at the National Portrait Gallery; why Turner is on his way to the National Gallery, Damien Hirst to Tate Modern? However it was done, the patriotic command has prompted a fine cluster of displays, of which Picasso and Modern British Art is probably the most surprising. A survey that ought to have felt dutiful doesn’t. Indeed, Picasso and Modern British Art is a misnomer. The show should really be called Picasso v British Art. And I’m afraid he wipes the floor with us.

Picasso’s relationship with Britain had many aspects, all of which are investigated in chronological order, starting with the first sighting of his work in 1910 in a pioneering postimpressionist display organised by the critic Roger Fry. By 1910, Picasso had already been through his Toulouse-Lautrec phase, his blue period, his rose period and his expressionist tribal period; he was three years into full-blown cubism. So the showing of two small works in Fry’s exhibition could only hint at his achievements so far. But that did not stop Colonel Blimp from picking up his pen. In GK Chesterton’s opinion, cubism was “a piece of paper on which Mr Picasso has had the misfortune to upset the ink and tried to dry it with his boots”. More than any other foreign artist, Picasso had the knack of stinging Colonel Blimps on the nose. It’s a talent he never lost.

He wasn’t lucky, either, in the quality of the British admirers he did manage to persuade. The first of the obvious groupies included here, Duncan Grant, a key member of Fry’s Bloomsbury group, was a truly dismal painter. What Picasso did naturally, Grant does as effortfully as a man following the instructions on an Ikea flatpack. A vase of flowers has been redone, ludicrously, in Picasso’s tribal style; a Bloomsbury nude attempts an African pose in colours imported from Morocco.

Remarkably, Grant turns out to have been a more sensitive Picasso copyist than Wyndham Lewis. From a distance, vorticism, of which Lewis was a founder, passes for a brave reworking of cubist discoveries, but, when you get closer, you encounter a set of paint surfaces as inert as a garage floor. As for the crazily grimacing figure studies prompted by Lewis’s misreading of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, not only is his touch jarring, the element of mockery he adds to the recipe takes us back into Blimp territory. Sticking a Picasso next to a Wyndham Lewis is like putting a Michelangelo next to an Andy Capp cartoon.

This show looks also at the wider question of Britain’s national taste and how it lagged behind. The first Picasso to enter a national collection was a vase of flowers, from 1901, bought by the Tate in 1933! It’s the most conservative Picasso in the show, and the only one that might pass for the work of a run-of-the-mill painter. With our national institutions at the back of the field, it was left to a clutch of inspired collectors to race ahead. The exciting central gallery is filled with examples from all of Picasso’s phases acquired by Douglas Cooper, Hugh Willoughby and Peter Watson. The result is a one-room retrospective that is all the better for featuring no British art whatsoever.

Cubism is easy to mistake for a dull and monkish aesthetic when there is a lot of it on show at once, but the few fine examples displayed here allow you to admire it in perfect quantities. The magnificent Man with a Clarinet (1911-12), which belonged to Douglas Cooper and is now, alas, in the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection in Madrid, is surprisingly full of colour: just subtle indoor colours, not sunny outdoor ones. In 1932, the obscure economist Oswald T Falk bought the gorgeous portrait of Marie-Thérèse Walter sitting naked in an armchair while it was still wet on the artist’s easel. The next year, the Dutch collector Frank Stoop donated a definitive example of Picasso’s classical style to the Tate: the lovely Seated Woman in a Chemise. All of which constitutes inspired, ballsy collecting.

The insouciance with which Picasso changed styles is, in itself, thoroughly un-British behaviour. Our artists tend to follow a single path to its bitter end. Picasso jumped where he fancied. And he did it successfully because all his many styles were built on the same infallible touch. He really was incapable of a graceless or ugly mark. It’s uncanny. When Picasso traces a secret profile of a loved one deep in the clutter of a cubist assemblage, the secret profile is perfectly positioned. When Ben Nicholson tries the same pictorial trick to record his love for Barbara Hepworth, the inserted face feels as crudely imported as a Venus at a garden centre.

Nicholson is actually this display’s most successful British contributor. His attempts to borrow Picasso’s extra-quick profiles don’t quite work, but the fully abstract paintings featuring carefully positioned rectangles and interconnected colour planes are beautifully composed. To my eyes, they have little in common with Picasso. Which is probably why they work.

Elsewhere in the display, artist after artist is shown up badly. Henry Moore, whom Picasso himself dismissed as a “petit maître”, is proved to have been a dramatically imitative petit maître. The basic proposition of Moore’s entire career — that the human body can be reduced to a series of suggestive reclining swellings and roundels — is fully instigated by Picasso in his short-lived surrealist phase. It’s all there: the tiny heads, the insistent echoes of genitalia, the dinosaur-ish air of lumpen primitivism. Francis Bacon’s art feasts on a similar helping of influences, but manages, in the rabid Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, to add a note of open-mouthed terror that you never find in Picasso.

The gallery that focuses on the Weeping Woman theme and Picasso’s spiky and committed art from the years 1937-39 is another highlight. In a show devoted from start to finish to the search for a new symbolic vocabulary in art, nothing is quite as awesomely effective as the Weeping Woman. The great Tate painting from 1937, which was passed to the nation by Roland Penrose, manages to express the terror of its times by adding the jagged atmosphere of a broken bottle to a mass of absurdly cheerful colours; a huge etching of the same year finds such brilliant metaphor for the global angst in the lumpy, misshapen, weeping profile of Dora Maar.

Poor old David Hockney is set the task of following that. He fails dismally. The Hockney section makes abundantly clear how much he took from Picasso, but also, unfortunately, how weedily he took it. The photo-collages in the cubist manner just about survive the comparison, but an attempt to paint the face of Christopher Isherwood in the style of an adjacent Picasso offers an unusually vivid opportunity to note Hockney’s difficulties. It’s an unfair contest that contributes to an overall Olympic score for the show of Picasso 10, British art 0.

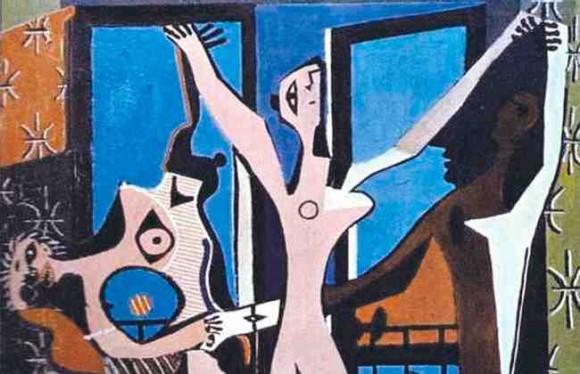

And that’s without counting the magnificent Three Dancers, which the organisers have cannily placed in the final room, thereby replacing the rightful whimper with a climactic bang.